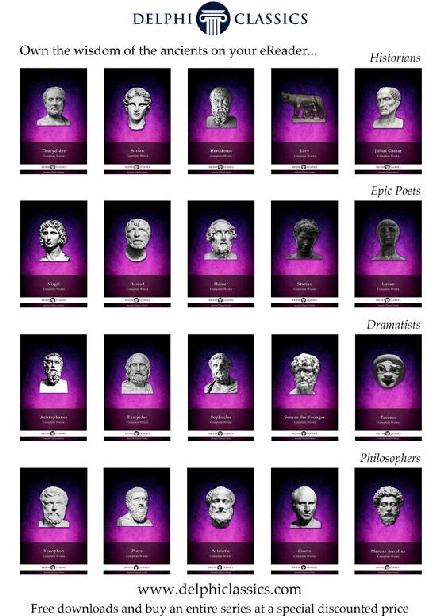

The Complete Works of

DIO CHRYSOSTOM

(AD 40c. 115)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2017

Version 1

The Complete Works of

DIO CHRYSOSTOM

By Delphi Classics, 2017

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Dio Chrysostom

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2017.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78656 390 3

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

Bursa, formerly Prusa in the Roman province of Bithynia, now a large city in north-western Turkey Dios birthplace

DISCOURSES

Translated by J. W. Cohoon

Dio Chrysostom was born at Prusa, now Bursa, in the Roman province of Bithynia in AD 40. His father, Pasicrates, is believed to have taken great care of his sons education and the early training of his mind. At first Dio occupied himself in his native town, where he held important offices, while composing speeches and other rhetorical and sophistical essays, but he later devoted himself with zeal to the study of philosophy, travelling to Rome to extend his learning, where he was eventually converted to Stoicism.

Dio formed part of the Second Sophistic school of Greek philosophers that reached its peak in the early second century. He was considered as one of the most eminent of the Greek rhetoricians by the ancients that wrote about him, including Philostratus, Synesius and Photius. His eighty extant Orations appear to be written versions of his oral teaching, similar in style to essays on political, moral and philosophical subjects. They include four orations on kingship addressed to Trajan on the virtues of a sovereign; four on the character of Diogenes of Sinope. Other topics include the troubles that men expose themselves to by deserting the path of Nature and the difficulties that a sovereign has to encounter.

There are also discourses on slavery and freedom, on the means of attaining eminence as an orator, as well as political essays addressed to various towns that Dio both praises and censures, though always with moderation and wisdom. The discourses also cover subjects of ethics and practical philosophy, which he treats in a popular and attractive manner; and lastly, there are orations on mythical subjects and show-speeches.

Dio wrote many other philosophical and historical works, none of which survive, except for fragments. The works that survive confirm his prominent influence in reviving Greek literature in the Roman Empire, marking the beginning of the Second Sophistic movement. Dio was committed to defending the ethical values of the Greek cultural tradition, as reflected by his sober and elegant style.

Orations of Dio Chrysostom edited by Johann Jakob Reiske, 1784

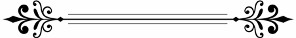

Statue of Diogenes at Sinop, Turkey Diogenes forms an important subject of Dios Discourses

CONTENTS

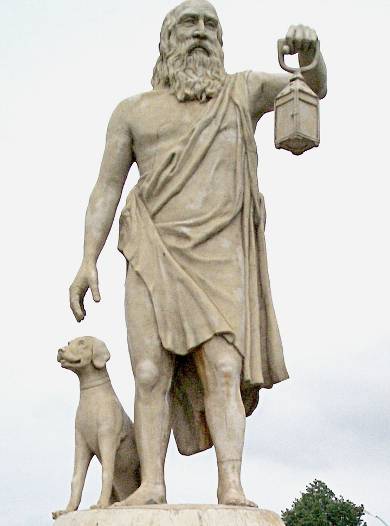

Marble bust of Trajan (AD 53-117) several of Dios Discourses are directly addressed to the Roman Emperor on the theme of kingship.

Photios I (c.810-c.893), was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 858 to 867 and from 877 to 886. He was a great advocate of the study of Dios works during the Dark Ages.

THE FIRST DISCOURSE ON KINGSHIP

The first Discourse as well as the following three has for its subject Kingship, and from internal evidence is thought to have been first delivered before Trajan in Rome immediately after he became emperor. At any rate Dio does not address the Emperor in those terms of intimacy that he uses in the third Discourse.

Dios conception of the true king is influenced greatly by Homer and Plato. The true king fears the gods and watches over his subjects even as Zeus, the supreme god, watches over all mankind. At the end is a description of the choice made by Heracles, who is the great model of the Cynics.

The First Discourse on Kingship

The story goes that when the flute-player Timotheus gave his first exhibition before King Alexander, he showed great musical skill in adapting his playing to the kings character by selecting a piece that was not languishing or slow nor of the kind that would cause relaxation or listlessness, but rather, I fancy, the ringing strain which bears Athenas name and none other. [2] They say, too, that Alexander at once bounded to his feet and ran for his arms like one possessed, such was the exaltation produced in him by the tones of the music and the rhythmic beat of the rendering. The reason why he was so affected was not so much the power of the music as the temperament of the king, which was high-strung and passionate. [3] Sardanapallus, for example, would never have been aroused to leave his chamber and the company of his women even by Marsyas himself or by Olympus, much less by Timotheus or any other of the later artists; nay, I believe that had even Athena herself were such a thing possible performed for him her own measure, that king would never have laid hand to arms, but would have been much more likely to leap up and dance a fling or else take to his heels; to so depraved a condition had unlimited power and indulgence brought him.

[4] In like manner it may fairly be demanded of me that I should show myself as skilful in my province as a master flautist may be in his, and that I should find words which shall be no whit less potent than his notes to inspire courage and high-mindedness [5] words, moreover, not set to a single mood but at once vigorous and gentle, challenging to war yet also speaking of peace, obedience to law, and true kingliness, inasmuch as they are addressed to one who is disposed, methinks, to be not only a brave but also a law-abiding ruler, one who needs not only high courage but high sense of right also. [6] If, for instance, the skill which Timotheus possessed in performing a warlike strain had been matched by the knowledge of such a composition as could make the soul just and prudent and temperate and humane, and could arouse a man not merely to take up arms but also to follow peace and concord, to honour the gods and to have consideration for men, it would have been a priceless boon to Alexander to have that man live with him as a companion, and to play for him, not only when he sacrificed but at other times also: [7] when, for example, he would give way to unreasoning grief regardless of propriety and decorum, or would punish more severely than custom or fairness allowed, or would rage fiercely at his own friends and comrades or disdain his mortal and real parents. [8] But unfortunately, skill and proficiency in music cannot provide perfect healing and complete relief for defect of character. No indeed! To quote the poet:

Next page