The Complete Works of

EPICTETUS

(AD 55135)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2018

Version 1

Browse Ancient Classics

The Complete Works of

EPICTETUS

By Delphi Classics, 2018

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Epictetus

First published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2018.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78656 395 8

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

Ruins at Hierapolis, Phrygia, south-western Anatolia, close to modern Pamukkale in Turkey Epictetus traditional birthplace

DISCOURSES

Translated by George Long and W. A. Oldfather

A Greek Stoic philosopher of the first and second century, Epictetus (c. AD 55 135) was a crippled Greek slave of Phrygia during Neros reign. He is recorded as having heard lectures by the Stoic Musonius before he was freed. Expelled with the other prominent philosophers of Rome by Domitian in c. 89, Epictetus settled permanently in Nicopolis in Epirus, where he founded his own school, which he called a healing place for sick souls. There he taught a practical philosophy, which has been detailed by his principal student Arrian, the famous author of the historical work Anabasis of Alexander the best source on the campaigns of Alexander the Great. Epictetus ideas have only survived through the works of Arrian. There are four books of Discourses and a smaller Encheiridion , a handbook that summarises the chief doctrines of the Discourses . Epictetus is believed to have lived into the reign of Hadrian.

The (Discourses) are a series of extracts of Epictetus teachings, set down by Arrian in c. AD 108. They were originally composed of eight books, but only four remain in their entirety, along with a few fragments of the lost books. In a preface attached to the text, Arrian narrates how he wrote the texts, explaining, I neither wrote these in the way in which a man might write such things; nor did I make them public myself, inasmuch as I declare that I did not even write them. But whatever I heard him say, the same I attempted to write down in his own words as nearly as possible, for the purpose of preserving them as memorials to myself afterwards of the thoughts and the freedom of speech of Epictetus.

The Discourses are unlikely to be exact transcriptions of Epictetus words, but are instead taken down in the form of lecture notes. They present Epictetus Stoic ethics as broad and firm in method, and occasionally humorous and gloomy in spirit. The work propounds challenging questions, such as How should one live righteously? The philosopher also presents a compelling demonstration of the ideal Stoic man.

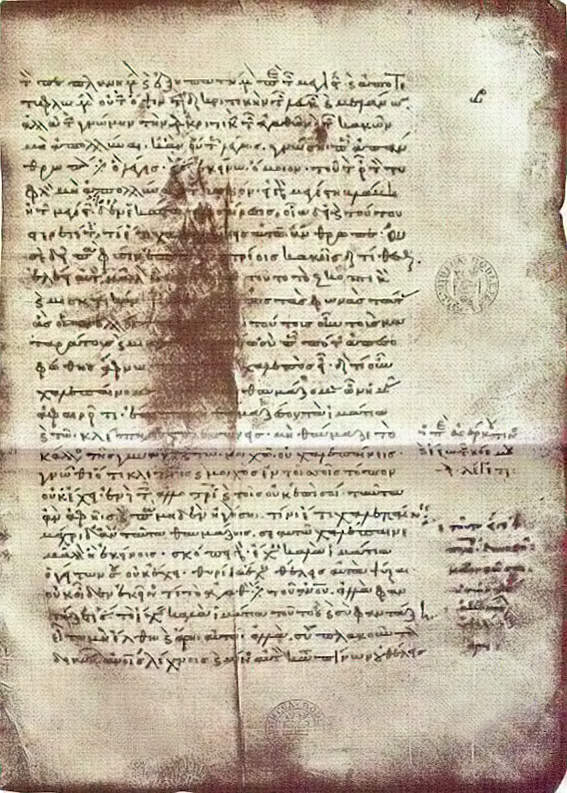

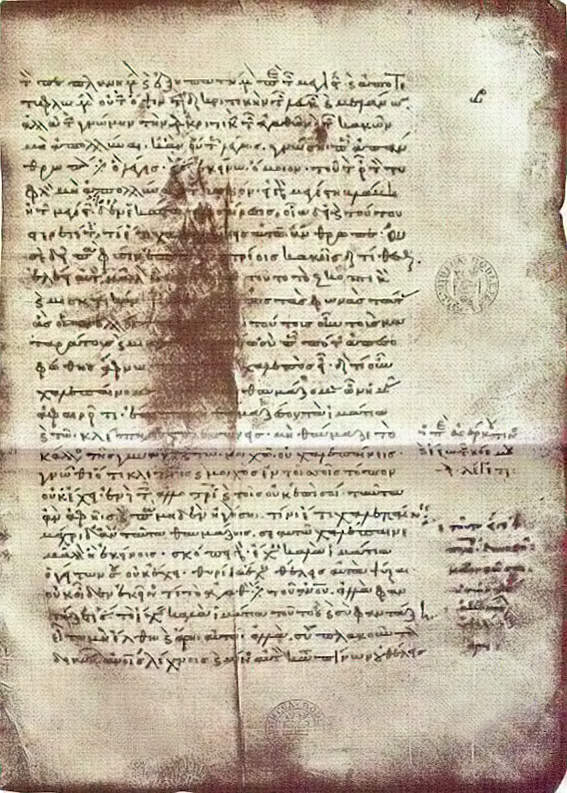

The earliest manuscript is a twelfth-century copy kept at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, which contains a blot on one of the pages, rendering a series of words illegible. As in all the other known manuscripts these words are omitted, we know that they must have been derived from the Bodleian copy.

The Codex Bodleianus of the Discourses

CONTENTS

A sixteenth century artists depiction of Epictetus

GEORGE LONG TRANSLATION, 1890

CONTENTS

ARRIAN TO LUCIUS GELLIUS, WITH WISHES FOR HIS HAPPINESS.

I NEITHER wrote these Discourses of Epictetus in the way in which a man might write such things; nor did I make them public myself, inasmuch as I declare that I did not even write them. But whatever I heard him say, the same I attempted to write down in his own words as nearly as possible, for the purpose of preserving them as memorials to myself afterwards of the thoughts and the freedom of speech of Epictetus. Accordingly, the Discourses are naturally such as a man would address without preparation to another, not such as a man would write with the view of others reading them. Now, being such, I do not know how they fell into the hands of the public, without either my consent or my knowledge. But it concerns me little if I shall be considered incompetent to write; and it concerns Epictetus not at all if any man shall despise his words; for at the time when he uttered them, it was plain that he had no other purpose than to move the minds of his hearers to the best things. If, indeed, these Discourses should produce this effect, they will have, I think, the result which the words of philosophers ought to have. But if they shall not, let those who read them know that, when Epictetus delivered them, the hearer could not avoid being affected in the way that Epictetus wished him to be. But if the Discourses themselves, as they are written, do not effect this result, it may be that the fault is mine, or, it may be, that the thing is unavoidable.

Farewell!

BOOK I.

Of the things which are in our power, and not in our power.

OF all the faculties (except that which I shall soon mention), you will find not one which is capable of contemplating itself, and, consequently, not capable either of approving or disapproving. How far does the grammatic art possess the contemplating power? As far as forming a judgment about what is written and spoken. And how far music? As far as judging about melody. Does either of them then contemplate itself? By no means. But when you must write something to your friend, grammar will tell you what words you should write; but whether you should write or not, grammar will not tell you. And so it is with music as to musical sounds; but whether you should sing at the present time and play on the lute, or do neither, music will not tell you. What faculty then will tell you? That which contemplates both itself and all other things. And what is this faculty? The rational faculty; for this is the only faculty that we have received which examines itself, what it is, and what power it has, and what is the value of this gift, and examines all other faculties: for what else is there which tells us that golden things are beautiful, for they do not say so themselves? Evidently it is the faculty which is capable of judging of appearances. What else judges of music, grammar, and the other faculties, proves their uses, and points out the occasions for using them? Nothing else.

Next page