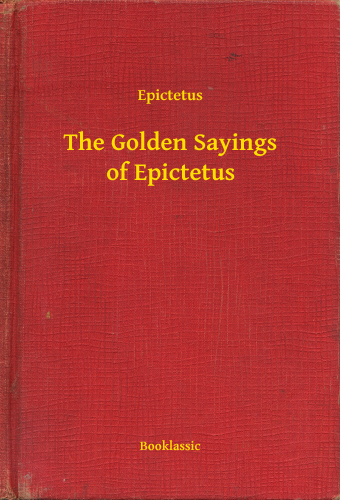

Epictetus - The Golden Sayings of Epictetus

Here you can read online Epictetus - The Golden Sayings of Epictetus full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Csorna, year: 1903;2015, publisher: Booklassic, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Golden Sayings of Epictetus: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Golden Sayings of Epictetus" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Golden Sayings of Epictetus — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Golden Sayings of Epictetus" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

2015

ISBN 978-963-524-684-7

I

Are these the only works of Providence in us? What words sufficeto praise or set them forth? Had we but understanding, should weever cease hymning and blessing the Divine Power, both openly andin secret, and telling of His gracious gifts? Whether digging orploughing or eating, should we not sing the hymn to God:

Great is God, for that He hath given us such instruments to tillthe ground withal: Great is God, for that He hath given us hands,and the power of swallowing and digesting; of unconsciously growingand breathing while we sleep!

Thus should we ever have sung: yea and this, the grandest anddivinest hymn of all:

Great is God, for that He hath given us a mind to apprehendthese things, and duly to use them!

What then! seeing that most of you are blinded, should there notbe some one to fill this place, and sing the hymn to God on behalfof all men? What else can I that am old and lame do but sing toGod? Were I a nightingale, I should do after the manner of anightingale. Were I a swan, I should do after the manner of a swan.But now, since I am a reasonable being, I must sing to God: that ismy work: I do it, nor will I desert this my post, as long as it isgranted me to hold it; and upon you too I call to join in thisself-same hymn.

II

How then do men act? As though one returning to his country whohad sojourned for the night in a fair inn, should be so captivatedthereby as to take up his abode there.

"Friend, thou hast forgotten thine intention! This was not thydestination, but only lay on the way thither."

"Nay, but it is a proper place."

"And how many more of the sort there be; only to pass throughupon thy way! Thy purpose was to return to thy country; to relievethy kinsmen's fears for thee; thyself to discharge the duties of acitizen; to marry a wife, to beget offspring, and to fill theappointed round of office. Thou didst not come to choose out whatplaces are most pleasant; but rather to return to that wherein thouwast born and where thou wert appointed to be a citizen."

III

Try to enjoy the great festival of life with other men.

IV

But I have one whom I must please, to whom I must be subject,whom I must obey: God, and those who come next to Him.(1) He hathentrusted me with myself: He hath made my will subject to myselfalone and given me rules for the right use thereof.

(1) I.e., "good and just men."

V

Rufus(2) used to say, If you have leisure to praise me, what Isay is naught. In truth he spoke in such wise, that each of us whosat there, thought that some one had accused him to Rufus: sosurely did he lay his finger on the very deeds we did: so surelydisplay the faults of each before his very eyes.

(2) C. Musonius Rufus, a Stoic philosopher, whose lecturesEpictetus had attended.

VI

But what saith God? "Had it been possible, Epictetus, I wouldhave made both that body of thine and thy possessions free andunimpeded, but as it is, be not deceived: it is not thine own; itis but finely tempered clay. Since then this I could not do, I havegiven thee a portion of Myself, in the power of desiring anddeclining and of pursuing and avoiding, and in a word the power ofdealing with the things of sense. And if thou neglect not this, butplace all that thou hast therein, thou shalt never be let orhindered; thou shalt never lament; thou shalt not blame or flatterany. What then? Seemeth this to thee a little thing?"Godforbid!"Be content then therewith!"

And so I pray the Gods.

VII

What saith Antisthenes?(3) Hast thou never heard?

It is a kingly thing, O Cyrus, to do well and to be evil spokenof.

(3) The founder of the Cynic school of philosophy.

VIII

"Aye, but to debase myself thus were unworthy of me."

"That," said Epictetus, "is for you to consider, not for me. Youknow yourself what you are worth in your own eyes; and at whatprice you will sell yourself. For men sell themselves at variousprices. This was why, when Florus was deliberating whether heshould appear at Nero's shows, taking part in the performancehimself, Agrippinus replied, 'Appear by all means.' And when Florusinquired, 'But why do not you appear?' he answered, 'Because I donot even consider the question.' For the man who has once stoopedto consider such questions, and to reckon up the value of externalthings, is not far from forgetting what manner of man he is. Why,what is it that you ask me? Is death preferable, or life? I reply,Life. Pain or pleasure? I reply, Pleasure."

"Well, but if I do not act, I shall lose my head."

"Then go and act! But for my part I will not act."

"Why?"

"Because you think yourself but one among the many threads whichmake up the texture of the doublet. You should aim at being likemen in generaljust as your thread has no ambition either to beanything distinguished compared with the other threads. But Idesire to be the purplethat small and shining part which makes therest seem fair and beautiful. Why then do you bid me become even asthe multitude? Then were I no longer the purple."

IX

If a man could be thoroughly penetrated, as he ought, with thisthought, that we are all in an especial manner sprung from God, andthat God is the Father of men as well as of Gods, full surely hewould never conceive aught ignoble or base of himself. Whereas ifCaesar were to adopt you, your haughty looks would be intolerable;will you not be elated at knowing that you are the son of God? Nowhowever it is not so with us: but seeing that in our birth thesetwo things are commingledthe body which we share with the animals,and the Reason and Thought which we share with the Gods, manydecline towards this unhappy kinship with the dead, few rise to theblessed kinship with the Divine. Since then every one must dealwith each thing according to the view which he forms about it,those few who hold that they are born for fidelity, modesty, andunerring sureness in dealing with the things of sense, neverconceive aught base or ignoble of themselves: but the multitude thecontrary. Why, what am I?A wretched human creature; with thismiserable flesh of mine. Miserable indeed! but you have somethingbetter than that paltry flesh of yours. Why then cling to the one,and neglect the other?

X

Thou art but a poor soul laden with a lifeless body.

XI

The other day I had an iron lamp placed beside my householdgods. I heard a noise at the door and on hastening down found mylamp carried off. I reflected that the culprit was in no verystrange case. "To-morrow, my friend," I said, "you will find anearthenware lamp; for a man can only lose what he has."

XII

The reason why I lost my lamp was that the thief was superior tome in vigilance. He paid however this price for the lamp, that inexchange for it he consented to become a thief: in exchange for it,to become faithless.

XIII

But God hath introduced Man to be a spectator of Himself and ofHis works; and not a spectator only, but also an interpreter ofthem. Wherefore it is a shame for man to begin and to leave offwhere the brutes do. Rather he should begin there, and leave offwhere Nature leaves off in us: and that is at contemplation, andunderstanding, and a manner of life that is in harmony withherself.

See then that ye die not without being spectators of thesethings.

XIV

You journey to Olympia to see the work of Phidias; and each ofyou holds it a misfortune not to have beheld these things beforeyou die. Whereas when there is no need even to take a journey, butyou are on the spot, with the works before you, have you no care tocontemplate and study these?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Golden Sayings of Epictetus»

Look at similar books to The Golden Sayings of Epictetus. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Golden Sayings of Epictetus and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.