The Works of NONNUS (fl. late 4 th century)

The Works of NONNUS (fl. late 4 th century)  Contents

Contents  Delphi Classics 2015 Version 1

Delphi Classics 2015 Version 1  The Works of NONNUS

The Works of NONNUS  By Delphi Classics, 2015 COPYRIGHT The Works of Nonnus First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics. Delphi Classics, 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. H. D. D.

By Delphi Classics, 2015 COPYRIGHT The Works of Nonnus First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics. Delphi Classics, 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. H. D. D.

Rouse Composed in 48 books, The Dionysiaca is the longest surviving epic poem from antiquity, comprising 20,426 lines and written in Homeric dialect and dactylic hexameters. Recounting the life of Dionysus, including his fabled expedition to India and his triumphant return to the west, the poem is thought to have been written in the late fourth or early fifth century. The Dionysiaca appears to be incomplete, with some scholars believing that a 49 th book was being planned when Nonnus stopped work on the poem, though others suggest that the number of 48 books is the same as the 48 books of the Iliad and Odyssey combined. It has also been argued by scholars that a possible conversion to Christianity or death caused Nonnus to abandon the poem after some revisions. They have identified various inconsistencies and difficulties in Book 39, appearing to be a disjointed series of descriptions, as evidence of the poems lack of revision. Others have attributed these problems to copyists or later editors, though most scholars now agree that the work is incomplete.

The primary models for The Dionysiaca are Homer and the Cyclic poets, as demonstrated by Nonnus Homeric language, metrics, episodes and the descriptive canons that abound in the poem. The influence of Euripides Bacchae is also significant. Though Nonnus debt to fragmentary and lost works is hard to appreciate, he alludes to earlier poets treatments of the life of Dionysus, such as the lost poems by Euphorion, Peisander of Larandas elaborate encyclopaedic mythological poem, Dionysius, and Soteirichus. Hesiods poetry (especially the Catalogue of Women ), Pindars odes and the works of Callimachus have also had a hand in inspiring Nonnus great work. The epic is notably varied in its organisation, as it is not arranged in a linear chronology, but instead in episodes, arranged by a loose chronological and themed order, similar to Ovids Metamorphoses . The poem states as its guiding principle poikilia , diversity in narrative, form and organisation.

The appearance of Proteus, a shape shifting god, in the proem is presented as a metaphor for Nonnus varied style. Nonnus employs the style of the epyllion for many of his narrative sections, such as his treatment of Ampelus in 1011, Nicaea in 1516, and Beroe in 4143. These epyllia are inserted into the general narrative framework and provide many of the epics highlights. Nonnus also employs synkrisis , comparison, throughout his poem, most notably in the comparison of Dionysus and other heroes in Book 25. The complex organisation and the richness of the language have caused the style of the poem to be termed Nonnian Baroque. The Dionysiaca is noted for its careful handling of dactylic hexameter and Nonnus innovation in metre.

Whereas Homer employs 32 varieties of hexameter lines, Nonnus only employs nine variations, avoiding elision, while adopting mostly weak caesurae, following a variety of euphonic and syllabic rules in word placement. It is especially significant that Nonnus was so precise with meter as the quantitative meter of classical poetry was giving way to stressed meter during his era. These metrical restraints encouraged the creation of new compounds, adjectives and fabricated words, and Nonnus epic reveals some of the greatest variety of coinages in any surviving Greek text. Nonnus seems to have been an important influence to the poets of Late Antiquity, especially Musaeus, Colluthus, Christodorus and Dracontius. Although it is difficult to determine whether Claudian influenced Nonnus or Nonnus influenced Claudian, the two poets reveal striking similarities in their treatments of the Persephone myth. Nonnus remained continuously important in the Byzantine world and his influence can be found in Genesius and Planudes.

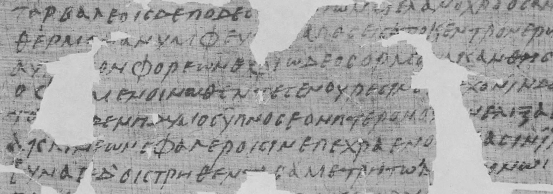

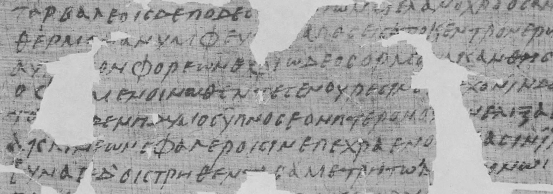

In the Renaissance, Poliziano popularised The Dionysiaca to the West and Goethe is recorded as admiring Nonnus work in the eighteenth century.  Detail of a papyrus codex showing Book 15 of The Dionysiaca, P.Berol. inv. 10567, 6th or 7th century CONTENTS

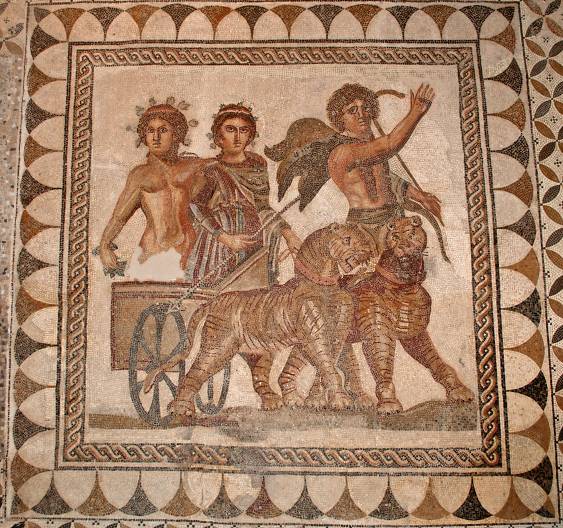

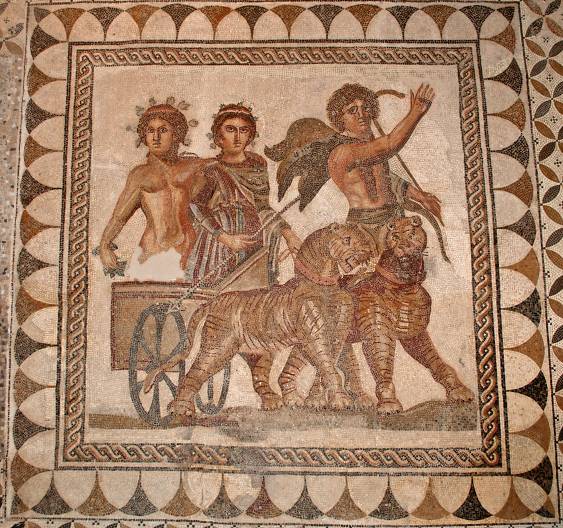

Detail of a papyrus codex showing Book 15 of The Dionysiaca, P.Berol. inv. 10567, 6th or 7th century CONTENTS  Bacchus in his panther-drawn chariot, as depicted in a third century mosaic from Seville

Bacchus in his panther-drawn chariot, as depicted in a third century mosaic from Seville  Lycurgus attacking the nymph Ambrosia VOLUME I. SUMMARY OF THE BOOKS OF THE POEM HEADINGS OF THE FIRST FIFTEEN BOOKS OF THE DIONYSIACA (1) The first contains Cronion, light-bearing ravisher of the nymph, and the starry heaven battered by Typhons hands. (3) In the third, look for the much-wandering ship of Cadmos, the palace of Electra and the hospitality of her table. (4) Tracking the fourth over the deep, you will see Harmonia sailing together with her agemate Cadmos. (5) Look into the fifth next, and you will see Actaion also, whom no pricket brought forth, torn by dogs as a fleeing fawn. (6) Look for marvels in the sixth, where in honouring Zagreus, all the settlements on the earth were drowned by Rainy Zeus. (7) The seventh sings of the hoary supplication of Time, and Semele, and the love of Zeus, and the furtive bed. (8) The eight has a changeful tale, the fierce jealousy of Hera, and Semeles fiery nuptials, and Zeus the slayer. (9) Look into the ninth, and you will see the son of Maia, and the daughters of Lamos, and Mystis, and the flight of Ino. (10) In the tenth also, you will see the madness of Athamas and Inos flight, how she fled into the swell of the sea with newborn Melicertes. (11) See the eleventh, and you will find lovely Ampelos carried off by the manslaying robber bull. (12) With the twelfth, delight your heart, where Ampelos has shot up his own shape, a new flower of love, into the fruit of the vine. (13) In the thirteenth, I will tell of a host innumerable, and champion heroes gathering for Dionysos. (14) Turn your mind to the fourteenth: there Rheia arms all the ranks of heaven for the Indian War. (15) In the fifteenth, I sing the sturdy Nicaia, the rosy-armed beast-slayer defying Love. (15) In the fifteenth, I sing the sturdy Nicaia, the rosy-armed beast-slayer defying Love.

Lycurgus attacking the nymph Ambrosia VOLUME I. SUMMARY OF THE BOOKS OF THE POEM HEADINGS OF THE FIRST FIFTEEN BOOKS OF THE DIONYSIACA (1) The first contains Cronion, light-bearing ravisher of the nymph, and the starry heaven battered by Typhons hands. (3) In the third, look for the much-wandering ship of Cadmos, the palace of Electra and the hospitality of her table. (4) Tracking the fourth over the deep, you will see Harmonia sailing together with her agemate Cadmos. (5) Look into the fifth next, and you will see Actaion also, whom no pricket brought forth, torn by dogs as a fleeing fawn. (6) Look for marvels in the sixth, where in honouring Zagreus, all the settlements on the earth were drowned by Rainy Zeus. (7) The seventh sings of the hoary supplication of Time, and Semele, and the love of Zeus, and the furtive bed. (8) The eight has a changeful tale, the fierce jealousy of Hera, and Semeles fiery nuptials, and Zeus the slayer. (9) Look into the ninth, and you will see the son of Maia, and the daughters of Lamos, and Mystis, and the flight of Ino. (10) In the tenth also, you will see the madness of Athamas and Inos flight, how she fled into the swell of the sea with newborn Melicertes. (11) See the eleventh, and you will find lovely Ampelos carried off by the manslaying robber bull. (12) With the twelfth, delight your heart, where Ampelos has shot up his own shape, a new flower of love, into the fruit of the vine. (13) In the thirteenth, I will tell of a host innumerable, and champion heroes gathering for Dionysos. (14) Turn your mind to the fourteenth: there Rheia arms all the ranks of heaven for the Indian War. (15) In the fifteenth, I sing the sturdy Nicaia, the rosy-armed beast-slayer defying Love. (15) In the fifteenth, I sing the sturdy Nicaia, the rosy-armed beast-slayer defying Love.

BOOK I The first contains Cronion, light-bearing ravisher of the nymph, and the starry heaven battered by Typhons hands. Tell the tale, Goddess, of Cronides courier with fiery flame, the gasping travail which the thunderbolt brought with sparks for wedding-torches, the lightning in waiting upon Semeles nuptials; tell the naissance of Bacchos twice-born, whom Zeus lifted still moist from the fire, a baby half-complete born without midwife; how with shrinking hands he cut the incision in his thigh and carried him in his mans womb, father and gracious mother at once and well he remembered another birth, when his own head conceived, when his temple was big with child, and he carried that incredible unbegotten lump, until he shot out Athena scintillating in her armour. [11] Bring me the fennel, rattle the cymbals, ye Muses! put in my hand the wand of Dionysos whom I sing: but bring me a partner for your dance in the neighbouring island of Paros, Proteus of many turns, that he may appear in all his diversity of shapes, since I twang my harp to a diversity of songs. For if, as a serpent, he should glide along his winding trail, I will sing my gods achievement, how with ivy-wreathed wand he destroyed the horrid hosts of Giants serpent-haired. If as a lion he shake his bristling mane, I will cry Euoi! to Bacchos on the arm of buxom Rheia, stealthily draining the breast of the lionbreeding goddess. If as a leopard he shoot up into the air with a stormy leap from his pads, changing shape like a master-craftsman, I will hymn the son of Zeus, how he slew the Indian nation, with his team of pards riding down the elephants.

Next page

The Works of NONNUS (fl. late 4 th century)

The Works of NONNUS (fl. late 4 th century)  Contents

Contents  Delphi Classics 2015 Version 1

Delphi Classics 2015 Version 1  The Works of NONNUS

The Works of NONNUS  By Delphi Classics, 2015 COPYRIGHT The Works of Nonnus First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics. Delphi Classics, 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. H. D. D.

By Delphi Classics, 2015 COPYRIGHT The Works of Nonnus First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics. Delphi Classics, 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. H. D. D. Detail of a papyrus codex showing Book 15 of The Dionysiaca, P.Berol. inv. 10567, 6th or 7th century CONTENTS

Detail of a papyrus codex showing Book 15 of The Dionysiaca, P.Berol. inv. 10567, 6th or 7th century CONTENTS  Bacchus in his panther-drawn chariot, as depicted in a third century mosaic from Seville

Bacchus in his panther-drawn chariot, as depicted in a third century mosaic from Seville  Lycurgus attacking the nymph Ambrosia VOLUME I. SUMMARY OF THE BOOKS OF THE POEM HEADINGS OF THE FIRST FIFTEEN BOOKS OF THE DIONYSIACA (1) The first contains Cronion, light-bearing ravisher of the nymph, and the starry heaven battered by Typhons hands. (3) In the third, look for the much-wandering ship of Cadmos, the palace of Electra and the hospitality of her table. (4) Tracking the fourth over the deep, you will see Harmonia sailing together with her agemate Cadmos. (5) Look into the fifth next, and you will see Actaion also, whom no pricket brought forth, torn by dogs as a fleeing fawn. (6) Look for marvels in the sixth, where in honouring Zagreus, all the settlements on the earth were drowned by Rainy Zeus. (7) The seventh sings of the hoary supplication of Time, and Semele, and the love of Zeus, and the furtive bed. (8) The eight has a changeful tale, the fierce jealousy of Hera, and Semeles fiery nuptials, and Zeus the slayer. (9) Look into the ninth, and you will see the son of Maia, and the daughters of Lamos, and Mystis, and the flight of Ino. (10) In the tenth also, you will see the madness of Athamas and Inos flight, how she fled into the swell of the sea with newborn Melicertes. (11) See the eleventh, and you will find lovely Ampelos carried off by the manslaying robber bull. (12) With the twelfth, delight your heart, where Ampelos has shot up his own shape, a new flower of love, into the fruit of the vine. (13) In the thirteenth, I will tell of a host innumerable, and champion heroes gathering for Dionysos. (14) Turn your mind to the fourteenth: there Rheia arms all the ranks of heaven for the Indian War. (15) In the fifteenth, I sing the sturdy Nicaia, the rosy-armed beast-slayer defying Love. (15) In the fifteenth, I sing the sturdy Nicaia, the rosy-armed beast-slayer defying Love.

Lycurgus attacking the nymph Ambrosia VOLUME I. SUMMARY OF THE BOOKS OF THE POEM HEADINGS OF THE FIRST FIFTEEN BOOKS OF THE DIONYSIACA (1) The first contains Cronion, light-bearing ravisher of the nymph, and the starry heaven battered by Typhons hands. (3) In the third, look for the much-wandering ship of Cadmos, the palace of Electra and the hospitality of her table. (4) Tracking the fourth over the deep, you will see Harmonia sailing together with her agemate Cadmos. (5) Look into the fifth next, and you will see Actaion also, whom no pricket brought forth, torn by dogs as a fleeing fawn. (6) Look for marvels in the sixth, where in honouring Zagreus, all the settlements on the earth were drowned by Rainy Zeus. (7) The seventh sings of the hoary supplication of Time, and Semele, and the love of Zeus, and the furtive bed. (8) The eight has a changeful tale, the fierce jealousy of Hera, and Semeles fiery nuptials, and Zeus the slayer. (9) Look into the ninth, and you will see the son of Maia, and the daughters of Lamos, and Mystis, and the flight of Ino. (10) In the tenth also, you will see the madness of Athamas and Inos flight, how she fled into the swell of the sea with newborn Melicertes. (11) See the eleventh, and you will find lovely Ampelos carried off by the manslaying robber bull. (12) With the twelfth, delight your heart, where Ampelos has shot up his own shape, a new flower of love, into the fruit of the vine. (13) In the thirteenth, I will tell of a host innumerable, and champion heroes gathering for Dionysos. (14) Turn your mind to the fourteenth: there Rheia arms all the ranks of heaven for the Indian War. (15) In the fifteenth, I sing the sturdy Nicaia, the rosy-armed beast-slayer defying Love. (15) In the fifteenth, I sing the sturdy Nicaia, the rosy-armed beast-slayer defying Love.