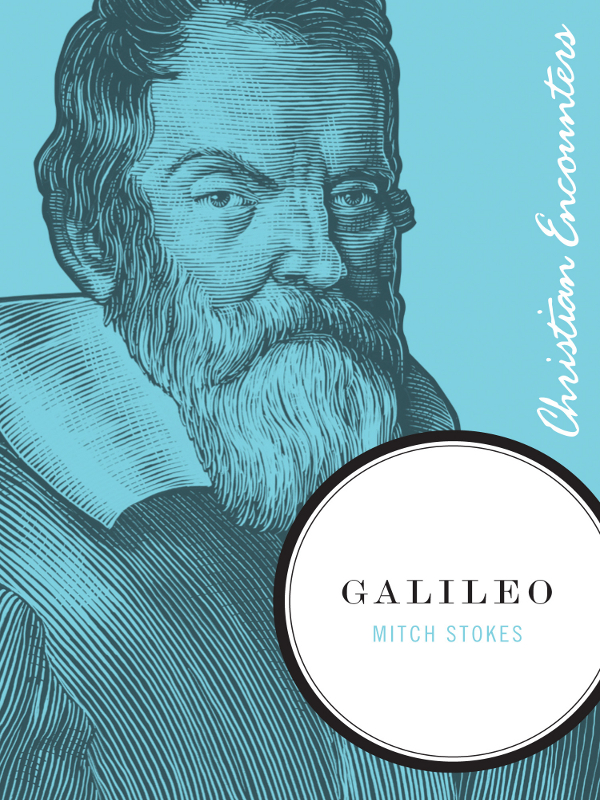

CHRISTIAN ENCOUNTERS

GALILEO

CHRISTIAN ENCOUNTERS

GALILEO

MITCH STOKES

2011 by Mitch Stokes

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a registered trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stokes, Mitch.

Galileo / by Mitch Stokes.

p. cm. (Christian encounters)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59555-031-6

1. Galilei, Galileo, 15641642 2. AstronomersItalyBiography. 3. PhysicistsItaly Biography. I. Title.

QB36.G2S87 2011

520.92dc22

[B]

2010036604

Printed in the United States of America

11 12 13 14 15 HCI 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR CHRISTINE,

AN ASTOUNDING WOMAN

CONTENTS

Preface

27. Death and Rehabilitation

It appears to me, that they who rely simply on the weight of authority to prove any assertion, without searching out the arguments to support it, act absurdly. I wish to question freely and to answer freely without any sort of adulation. That well becomes any who are sincere in the search for truth.

T his heroic passagewritten by Galileos father, Vincenzioappears in many biographies of Galileo.

This is the Galileo we know, an individualistic man of science, daringly opposed to all authority but his own. And tragically, martyrdom was his heros reward. But like those of many martyrs, Galileos sufferings have given those who have taken up his cause the courage to stand firm in a storm of benighted oppression. Especially benighted religious oppression.

This is indeed a stirring image of Galileo, one that has inspired plays, television specials, and even an opera. But, just like Vincenzios passage above, this portrait of Galileo is historically inaccurate. Facts have an annoying way of disappointing.

In the case of Vincenzios quotation, we now know that it was altered from the original, perhaps unintentionally, but just enough to make it entirely misleading.

Galileos biographers are therefore quite right: Vincenzio did bequeath his view of authority to his Galileo. But because of his heritage, Galileo never once balked at the authority of the Church, even when he could safely do so.

In fact, near the end of his life, Galileo counted his own zeal for the Church as one of his greatest consolations. Regarding his condemnation by the Catholic Church, Galileo wrote privately to a friend:

This afflicts me less than people may think possible, for I have two sources of perpetual comfortfirst, that in my writings there cannot be found the faintest shadow of irreverence towards the Holy Church; and second, the testimony of my own conscience, which only I and God in Heaven thoroughly know. And He knows that in this cause for which I suffer, though many might have spoken with more learning, none, not even the ancient Fathers, have spoken with more piety or with greater zeal for the Church than I.

Notice that Galileo said that his suffering was for the sake of a cause. This cause was not that of Copernicanism or even of science in general. Rather, says the Galilean historian Stillman Drake, The cause for which Galileo suffered, in his own view, was clearly not Copernicanism but sound theology and Christian zeal. Drake goes on to say:

Galileos own conscience was clear both as Catholic and as scientist. On one occasion he wrote, almost in despair, that at times he felt like burning all his work in science but he never so much as thought of turning his back on his faith.

Galileo, we are surprised to hear, was a devout Christian, and his debate with theologians was an internal Catholic debate over the interpretation of Scripture. It was neveragain we are shockeda debate between a proponent of secular science on the one hand and the adherents of religious faith on the other.

But to see this, we cant ignore the details of Galileos life and scientific work. For one thing, the Galileo affair, as it is now called, resulted largely from an ignorance of mathematics and science. This fact should give us considerable pause today, widespread avoidance of math and science is clich. For another thing, the myths that have grown around the Galileo affairespecially the myth that science and religion are natural enemieshave been the result of a convenient neglect of facts.

The paradox is this: Galileos story, as it has come to us, is at once clouded and stripped bare. And to get an accurate picture of the Galileo affair, we must study more than isolated and impersonal facts; we must study a life.

1

FROM MONKS

TO MEDICINE

A ccording to Italian custom, we know Galileo by his first name. This was an honor conferred upon him even in his own lifetime; he was one of a kind, requiring only his first name to single him out. He belongs to that special group of Italians who have contributed not only to Italys splendor, but to our races: Dante, Michelangelo, Raphael, and, nearer our own time, Madonna. But Galileos first name is also his last. Galileo Galilei. And perhaps a man with two first names need only go by one of them.

Galileo could trace his ancestry back to the 1200s, to a Florentine who had not a single Galileo to his name: Giovanni Bonaiuti. But Giovannis great-grandson, Galileo Bonaiuti was a man of distinction, an official at the University of Florence and a professor of medicine. And he wasnt a mere academic. He had a successful medical practice, though given the state of health care in that time, success was measured on a curve.

Bonaiuti also had a distinguished political career as a member of Florences governing council. Being involved in city government was substantially more impressive in Renaissance Italy than being, say, a mayor or city counselor today. Cities were the most powerful political entities in Italy: Venice, Florence, and, of course, Rome. Italy, in truth, didnt even exist during this time. The Italian state wouldnt be created until 1861. Italy was simply the boot-shaped landmass jutting into the Mediterranean, controlled by a number of duchies and republics, each looking out for itself.

Galileo Bonaiutis achievements were considerable; therefore, when he died around 1450, a proud relative considered Galileo worthy enough to be the founder of a new and eminent Florentine family. On Bonaiutis tombstone, this relative inscribed Galileis de Galilei, at one time Bonaiutis. The name stuck. Both of them.

Eighty years later, in 1520, the Galilei family was still distinguished, although its financial station, if not its pedigree, had declined significantly. In this year, Vincenzio Galilei was born in Florence. Vincenzio, and his son Galileo

Next page