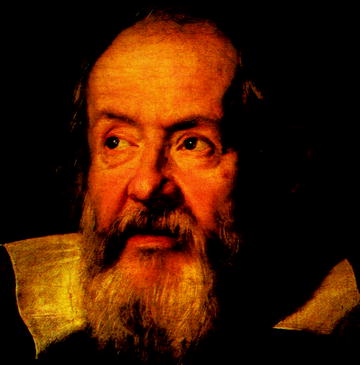

Our storys central figure, the Italian physicist Galileo Galilei (15641642), was intellectually active during the late Renaissance, an exciting and unprecedented period in history. Discoveries in the New World were opening eyes to the idea that our own planet was far vaster and more diverse than anyone had previously dared to suspect. Not only were new discoveries easily disseminated to the educated masses by the printing press, but new ways of thinking about the world were promulgated through pamphlets and books, often couched in the medium of fictional literature.

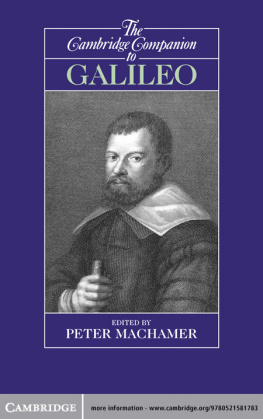

Galileo Galilei, portrayed by Justus Sustermans in 1636

Living and working from within some of the Catholic Churchs strongest domains first as Professor of Mathematics at Pisa and later in the Venetian Republic at Padua Galileos line of solid scientific reasoning led him to challenge many of the tenets about the Universe that the establishment held dear. Yet, Galileo didnt arrive on the scene amid a vacuum of ideas about how the Universe worked; the trouble was that many of the ideas prevalent at the time were only promulgated through the medium of accepted dogma. Religion has never been very good at shifting its ground once its leaders have proclaimed something to be true, and Galileos work was truly Earth-shaking.

Some of Galileos evidence-based notions were far from new for example, the theory that Earth was a planet in orbit around the Sun had been around since the third century BCE and had famously been postulated by Nicolaus Copernicus (14731543) a century before Galileo. However, it was the manner in which Galileo presented his ideas theories based on sound observations backed up by solid mathematical foundations that gave the scientists work such potency. It was with good reason that Albert Einstein (18791955) bestowed Galileo with the accolade the father of modern science. Galileos work especially his stance on the correctness of the heliocentric theory led him to a famous historical clash with the then-powerful Church authorities.

Before looking at the life and work of Galileo, particularly with respect to his work in astronomy and his astonishing telescopic discoveries, its important to understand how our human view of the Universe and our place within it has been shaped over time.

Pre-Telescopic Astronomical Ideas, Inventions and Discoveries

Although astronomy, the oldest of all natural philosophical pursuits, experienced its dramatic introduction to the telescope just four centuries ago, this age-old science was no stranger to its practitioners use of mechanical devices for computation and observation. For many centuries astronomical calculations had been aided by wonders such as abacuses and astrolabes, and the heavens had been charted and monitored with quadrants, cross staffs, and a variety of other finely crafted naked-eye instruments.

Regardless of the substantial body of astronomical knowledge that had been acquired since ancient times, though, the telescope proved to be such a potent invention that it changed everything overnight. Not only were the heavens discovered to be more complex and more beautiful than anyone had dared to imagine, its no overstatement to claim that humanitys perspective upon its own position and status in the Universe changed forever.

Enquiring and observant people throughout the ages have made remarkable efforts to understand the Universe and its workings using nothing but their unaided eyes and raw brain power. So, before exploring the extraordinary development of the telescope, from its humble beginnings through progressively larger and ever-more optically perfect instruments to the incredibly sensitive eyes on the Universe planned for the twenty-first century, lets review some of the important events of pre-telescopic astronomy.

For most of human history, most people lived in small rural settlements and enjoyed truly dark night skies that were untainted by the glare of artificial lighting. Our remote ancestors of millennia gone by could not have failed to have been struck by the sheer grandeur of the heavens. This is a point often unappreciated by most twenty-first century people. More than 3.3 billion people (half the worlds population) now reside in cramped towns and sprawling cities. Few occupants of Earths urban areas appreciate that beyond the orange-tinted artificial sky glow of their night sky lies one of natures most glorious sights. As urban communities are bathed in permanent light and the night air above glows with countless particles reflecting the glare of street lighting, industry, and commerce, their residents are simply never given the chance to appreciate the darkness. Sadly, few people realize just how magnificent the night skies can be when viewed with the unaided eye.

Our remote ancestors enjoyed incredibly dark skies, where people with average eyesight could easily discern the Milky Way, glowing like a phosphorescent river spanning the skies from horizon to horizon, with dozens of nebulae and star clusters punctuating its course like brighter eddies in the current. Further afield, the nebulous patches of the two close galaxies in Andromeda and Triangulum can be made out indistinctly against the blackness of pristine skies, and southern hemisphere viewers blessed with dark skies delight in the diffuse brightness of the two Magellanic Clouds, our Galaxys nearest cosmic neighbors.

Against this splendid stellar backdrop a celestial vault that seemed to revolve around Earth with the passing of the seasons the Sun made its way unerringly in its annual course along a path known as the ecliptic. The Moons monthly path among the stars was roughly in line with the Suns path hence the name ecliptic, since every so often the Moon occasionally eclipsed the Sun, and in turn the Moon was eclipsed by the broad shadow of Earth. Eclipse phenomena, along with the regular cycle of lunar phases, gave the Moon an air of profound mystery. Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn the five brightest planets, all of which have been known since antiquity each appeared to follow their own individual paths near the ecliptic, but at varying speeds. Their motion among the stars caused them to be known as the wanderers (the word planet derives from the ancient Greek).

In addition to the more readily visible celestial objects there were many sky phenomena whose appearance was dramatic, unpredictable, and often alarming to our ancestors. From time to time, meteors and fireballs streaked across the night skies; comets sometimes appeared from nowhere to develop into fiery torches with streaming tails; now and again, aurorae lit up the skies in intricate, shifting multicolored displays; occasionally, new stars blazed among the familiar constellations, only to fade into obscurity before long.