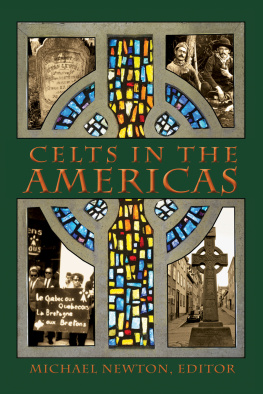

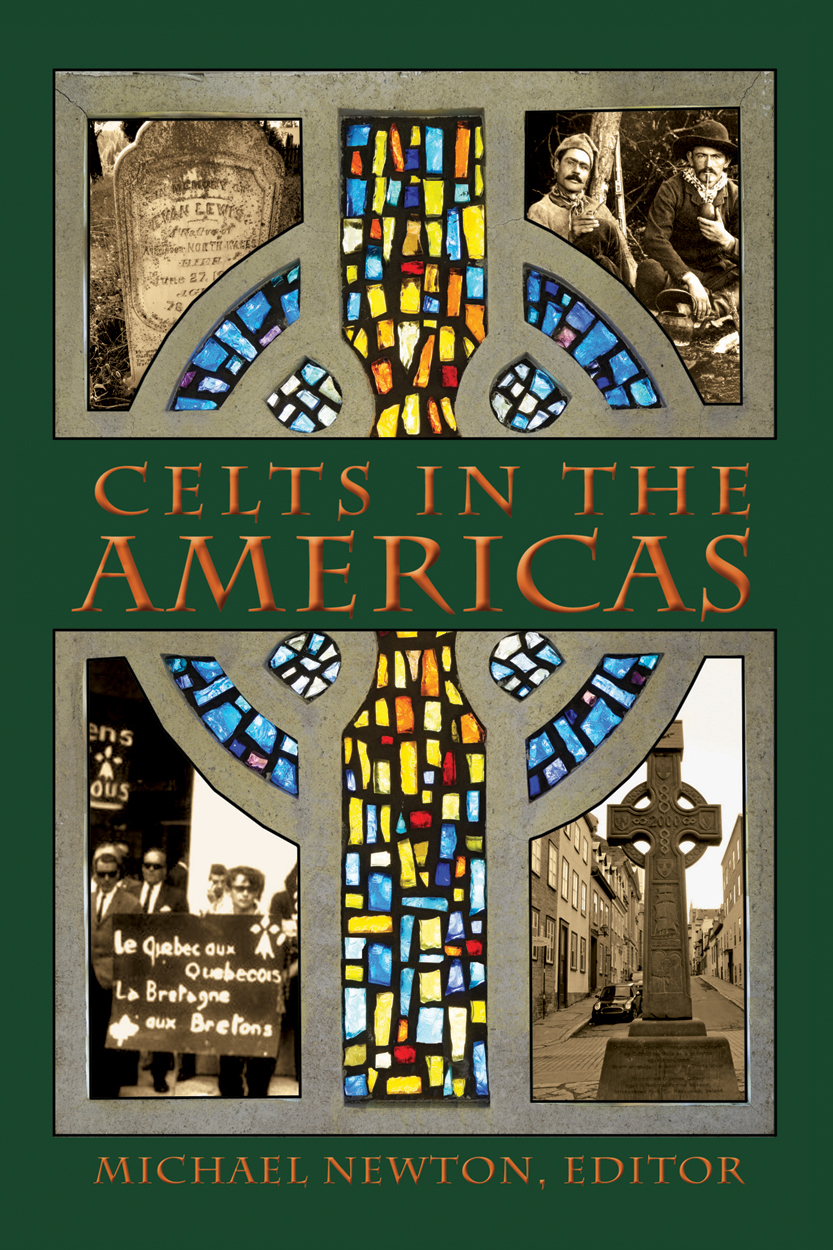

Celts in the Americas

Celts

in the

Americas

Michael Newton, Editor

CAPE BRETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

SYDNEY, NOVA SCOTIA

Copyright 2013 - Cape Breton University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Responsibility for the research and the permissions obtained for this publication rests with the authors.

Cape Breton University Press recognizes the support of the Province of Nova Scotia, through the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage and the support received for its publishing program from the Canada Council for the Arts Block Grants Program. We are pleased to work in partnership with these bodies to develop and promote our cultural resources.

Communities, Culture and Heritage

Cover images: (clockwise from upper right) Welshmen in Patagonia (see p. 256); High cross, Qubec City (see p. 63); Breton demonstration (see p. 31); Welsh gravestone (see p. 103)

Cover design: Cathy MacLean Design, Pleasant Bay, NS

Layout: Laura Bast, Sydney, NS

eBook development: WildElement.ca

First printed in Canada

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Celts in the Americas / edited by Michael Newton.

Based on papers presented at a conference held at St. Francis Xavier University, June 29-July 2, 2011.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-897009-75-8 (print)

ISBN 978-1-927492-27-7 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-927492-28-4 (Kindle)

1. Celts--America--Congresses. 2. Civilization, Celtic--Congresses. I. Newton, Michael Steven, 1965-

CB206.C44 2013 909.04916 C2013-901416-0

Cape Breton University Press

PO Box 5300

1250 Grand Lake Road

Sydney, NS B1P 6L2 CA

www.cbu.ca/press

Table of Contents

Michael Newton, Robert Dunbar, Gearid hAllmhurin and Daniel G. Williams

va Guillorel and Josette Jouas

Bernard Deacon

Toms h-de

Michael Newton

Gethin Matthews

Robert Dunbar

Ian Johnson

Emily McEwan-Fujita

rt III: Cultural Expression

Gearid hAllmhurin

Shamus Y. MacDonald

Natasha Sumner

Paul W. Birt

Rhiannon Heledd Williams

Michael Newton

C. Alexander MacLennan

Daniel G. Williams

Simon Brooks

va Guillorel

Michael Newton, Robert Dunbar, Gearid hAllmhurin and Daniel Williams

Introduction: The Past and Future Celt

Lost Legacies

As subjects of jealously hegemonic rulers, the monolithic term British (or French in the case of the Bretons) has obscured and eclipsed the identity and historical experiences of Celtic-speaking peoples in the Americas. As colonial offshoots of an essentially English empire, most scholars of Canadian and American history have been content to perpetuate an anglocentric master narrative. R. R. Davies has pointed out that

this essentially Anglocentric approach has been in effect the dominant historiographic tradition in England from at least the twelfth century to the twentieth centuries. Furthermore it has been, and remains, the determining paradigm in historical writing about the British Isles generally. (2000: 2)

Despite the efforts of the English Crown to impose a single anglocentric identity upon the various peoples it claimed as subjects, the British Isles have never been a homogenous cultural entity. Celtic languages and cultures have persisted to the present, even if driven to the margins. As late as 1500, about half the geographical area of the British Isles was still predominantly Celtic speaking (Ellis 2004: 223).

Within Celtic studies, Celticity is not framed in geographical or racial termsit is, rather, an abstraction for peoples speaking languages derived from a common ancestor and sharing cultural features that are directly related to this ancestral cultural core, regardless of their genetic makeup or territory (Koch 2003). Just as it is not possible to simply be an Indigenous Amer

Many previous investigations into Celts in the Americas have foundered on the rocks of a false essentialism. Some have equated Celticity with rusticity, unaware of the sophisticated lite cultures of Celtic peoples that were annihilated as a consequence of cultural conquest. The attempt to derive the cracker culture of the American South from Celts, and thus distinguish it from that of the North in the pre-Civil War era, was plagued by this error (Berthoff 1986; Newton 2006). Some have attributed Celtic origins to cultural features that once enjoyed much wider currency, even in anglophone societies. Few aficionados of what generally passes as Celtic music appreciate that it is a very modern medley of elements and that much of what has been preserved in the Celtic fringe had very close counterparts in England and elsewhere before being obscured and eclipsed by industrialization (Chapman 1994; Roberts 2012). Indeed, as hAllmhurins chapter in this volume adeptly explains, Celtic music has accumulated numerous layers of global flows of various sorts. Finally, some scholars have associated Celticity with entire nationsIreland, Scotland or Wales, for exampleeven though they have all had settler colonies since the high medieval period which cannot be properly considered Celtic. Thus, characterizing all Scottish emigrants as Celtic, for example, creates the fallacious categorization of Lowland features (many having Germanic origins) as Celtic, thus leading to further miscalculations.

Although it is a secondary phenomenon, one of the common formative experiences of Celtic communities (with the exception of the Bretons) has been conflict with an aggressively expansionist anglophone state. It is ironic that cultures that have spent centuries in opposition to English hegemony should be represented as synonymous to it in mainstream discourse. Michael Kennedy notes that

within Canadas two founding nations model, a cultural group once considered nearly antithetical to North American English culture has been redefined as somehow inherently English. As an ethnic group, Scottish Gaels quite simply do not exist within the context of Canadian cultural history. (2002: 28)

The efforts of Celtic studies scholars and advocates of various Celtic heritages notwithstanding, government publications articulating national narratives still reiterate these telescoped imperial identities. For example, the current handbook about Canadian history and identity for those aspiring to become Canadian citizens states:

The basic way of life in English-speaking areas was established by hundreds of thousands of English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish settlers, soldiers and migrants from the 1600s to the 20th century. Generations of pioneers and builders of British origins, as well as other groups, invested and endured hardship in laying the foundations of our country. This helps explain why Anglophones (English speakers) are generally referred to as English Canadians. (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2011: 12)

A recognition of the social construction of knowledge will help us to make sense of the discrepancies between these historiographic fictions and historical reality (a topic further explored by Dunbar in this volume). Educational institutions were not established as unbiased centres of purely objective intellectual exploration but were inextricably tied to the ideologies of the empires and nation-states who built and ran them. The knowledge they produced was part of the enterprise of the domination of populations. Linguistic and cultural diversity was perceived as destabilizing and threatening in both British and French Empires, and so, until recently, official institutions, including those of education, rarely encouraged Celtic languages and cultures to be living entities. Being members of subordinated societies impeded the establishment of institutions representative of the Celts own cultures empowered to act on their own behalf, whether in European homelands or in diasporic contexts.