CELTS

THE HISTORY AND LEGACY OF ONE

OF THE OLDEST CULTURES IN EUROPE

MARTIN J. DOUGHERTY

This digital edition first published in 2015

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

7477 White Lion Street

London N1 9PF

United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Appstore: itunes.com/apps/amberbooksltd

Facebook: www.facebook.com/amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright 2015 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-78274-174-9

Picture Credits

AKG Images, Alamy, Alamy/The Art Archive, Alamy/Interfoto, Alamy/David Lyons, Alamy/North Wind Picture Archive, Amber Books, Bridgeman Art Library, Corbis, Dorling Kindersley, Dreamstime, Mary Evans Picture Library, Werner Forman Archive, Werner Forman Archive/British Museum, Fotolia, Fotolia/Erica Guilane-Nachez, Getty Images, Getty Images/Bridgeman Art Library, iStock, Public Domain, TopFoto.

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge.

All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Other titles in the series:

Vikings

CONTENTS

Chapter One

Who Were the Celts?

Chapter Two

Celtic Society

Chapter Three

Celtic Art and Religion

Chapter Four

Celtic Myths and Legends

Chapter Five

Technology and Warfare

Chapter Six

Expansion and Decline in Europe

Chapter Seven

The Celts in Gaul

Chapter Eight

The Celts in the British Isles

INTRODUCTION

The Celts are a mysterious people whose history is shrouded in myth and misinformation. The latter stems largely from the fact that many of the Celtic people were opponents of the Roman Empire, and of course it was the victors that wrote the history books. Thus much of what we know about the Celts is distorted by Roman misunderstanding or misrepresentation, further coloured by later generations veneration of Rome.

The fashion for all things classical in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries led to the widespread belief that Ancient Greece and Rome were the source of all cultural virtue, and thus by definition the barbarians that opposed these civilizations were filthy, uncultured savages who needed saving from themselves at the point of a sword. The image put forward in Roman writings is one of bringing the light of civilization to the dark and savage corners of the world, and since much of what Celts might have recorded about themselves was destroyed in the process this concept became the widely accepted version of events.

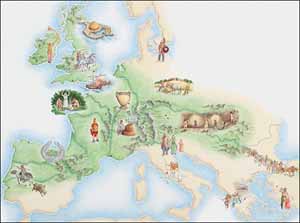

Celts spread across Europe from the Atlantic coasts to the Danube basin, and even into Asia Minor. Over such a large area, regional variations in their culture were inevitable, but a distinctive Celticness can still be discerned.

On the mainland of Europe, Celtic society was absorbed into the Roman Empire and changed enormously, while in the British Isles there were other influences that caused the Celts to change over time. Much of what we know about the Celts has been pieced together from fragmentary evidence or biased accounts, but one truth has emerged: they were anything but uncivilized.

Although todays popular view of the Celts is still influenced by the version accepted in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we are beginning to understand these people a lot better, and to realize just how influential they were upon the course of European history. This is hardly surprising the Celts were a widespread and numerous people who settled in much of Europe and the British Isles.

Early interactions between Celts and Romans had profound consequences for the future of Europe. Had relations not broken down, leading to the sacking of Rome, history might have taken a very different course.

Small wonder, then, that as the Roman Republic expanded its sphere of influence it came into contact with Celtic people. Relations were sometimes good, sometimes less so. It was a Celtic army that sacked Rome around 390 BCE, leading to a military revolution that ultimately created the all-conquering legions. It was Celts, usually referred to as Gauls by the Romans, who provided much of the resistance to Roman expansion in Europe. Without proud Gallic warriors on the opposing side, the glory of Rome might have shone less brightly. After all, glory is won by defeating worthy opponents and the Celts certainly were that.

Survival of the Celts

The culture of the European Gauls was largely absorbed into that of the Roman Empire, and some elements were distorted or destroyed. However, this was a two-way street to some extent, and Celtic influences did find their way into the Roman culture. In areas that were less thoroughly Romanized, or which were not conquered at all, the Celtic way of life survived and was melded with other cultures. While the tongue of the Roman Empire, Latin, is a dead language, some Celtic languages are still spoken today.

The Roman Empire did not reach Ireland, and attempts to push into Scotland were fought to a standstill until the Empire ceased to expand. Tribes in the border region traded with Rome, generally via Roman Britain, and absorbed some elements of Roman culture while remaining independent. Beyond this border zone the Roman influence was much less, and Celtic society continued as it had for generations before.

The Celtic languages live on mainly in Scotland and Ireland, with significant numbers of speakers in Canada and some cities of the USA. They are minority tongues, but proudly clung to by their speakers as a symbol of independence and an honourable heritage.

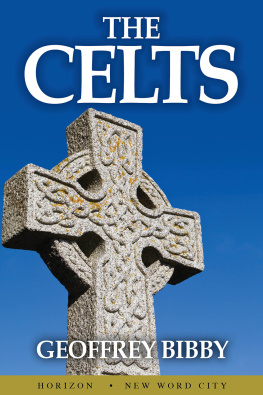

The Celtic Cross is an important symbol of early Christianity. Once they adopted the new religion, the Celts were instrumental in spreading it, and in so doing helped shape the development of the early Church.

Although the Celtic languages are diminishing, some elements of Celtic society have found their way into the mainstream of modern culture. Traditional folklore and even everyday practices have in some cases come from the Celtic people. It is possible that the habit of throwing coins into a fountain or pool for good luck is derived from a Celtic ritual, or from an even earlier era. Some traditional monsters and otherworldly spirits also bear a distinct resemblance to those of Celtic mythology.

Many place names in Europe are Celtic in origin, and have been inhabited since the heyday of Celtic culture. Often, once a settlements pattern has been established it survives through subsequent rebuilding, with the general layout of streets and squares remaining roughly the same from the Iron Age. Thus in some towns and cities we can today walk the same paths as our ancestors, stopping to browse the wares of a market that has been held in the same square for hundreds of years. In wilder places, fragments of Celtic society still remain in the form of standing stones and monuments of long-ago forgotten events.