WAR, WOMEN, AND DRUIDS

BY PHILIP FREEMAN

WAR, WOMEN, AND DRUIDS

EYEWITNESS REPORTS AND EARLY ACCOUNTS OF THE ANCIENT CELTS

University of Texas Press

Austin

Copyright 2002 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2002

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Freeman, Philip, 1961

War, women, and druids : eyewitness reports and early accounts of the ancient Celts / by Philip Freeman.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-292-72545-0 (alk. paper)

1. Civilization, CelticSources. 2. Druids and DruidismSources. 3. CeltsEuropeSources. 4. CeltsReligionSources. 5. Women, CelticSources. 1. Title.

D70 .F74 2002

936.4dc21 2002002779

ISBN 978-0-292-75639-7 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-78913-5 (individual e-book)

For my mother and father

PREFACE

The ancient Celts capture the modern imagination as do few other people of classical times. Naked barbarians charging the Roman legions, Druids performing sacrifices of unspeakable horror, women fighting beside their men and even leading armiesthese, along with stunning works of art, are the images most of us call to mind when we think of the Celts. And for the most part, these images are firmly based in the descriptions handed down to us by the Greek and Roman writers.

As with historical sources from any age, we cannot accept at face value everything the classical authors say about the Celts and we must always approach their words with caution. Every ancient (and modern) writer has particular motives and prejudices, even when they are attempting to portray an honest picture of Celtic life. Some authors, such as Julius Caesar, are anxious to present a brave and nobleif somewhat peculiarenemy in order to enhance their own achievements in conquering them. Other writers seek to show the Celts as noble savages embodying the high moral philosophy lost in Roman culture. On the other hand, some delight in portraying the Celts as disgusting barbarians desperately in need of a good dose of civilization. But most ancient authors are simply trying to record as accurately as possible for their own various purposes what they have seen, heard, or read of Celtic life.

Even with these shortcomings, the writings of the Greeks and Romans are our primary source of information on the ancient Celts. Archaeology has unearthed beautiful works of art and revealed much about Celtic culture, but nothing can replace the testimony of contemporary witnesses. In this book I try to present that testimony clearly to all interested readers. I have kept the introductory comments to the passages at a minimum in order to let the Greeks and Romans speak for themselves about the Celts. In my translations of the original sources, whether Greek or Latin, I have always tried to be faithful to the texts, but sometimes a loose translation or even paraphrase of the original author best conveys the meaning to modern readers.

The final chapter contains translations of inscriptions written by the ancient Celts themselves rather than the Greeks or Romans. These sources are limited and often are poorly understood even by specialists, but they provide a unique glimpse of ancient Celtic life through the words of those who lived it.

I have avoided the scholarly temptation to add tedious footnotes to every section, though a list of secondary sources is included at the end of the book for readers seeking to learn more about the fascinating world of the ancient Celts.

I owe many thanks to those experts in Classical and Celtic studies who read the manuscript of this book, especially Patrick Ford, Joseph Eska, John Carey, Pamela Hopkins, Katherine Forsyth, Thomas Clancy, Jerry Hunter, and Barbara Hillers.

WAR, WOMEN, AND DRUIDS

WAR

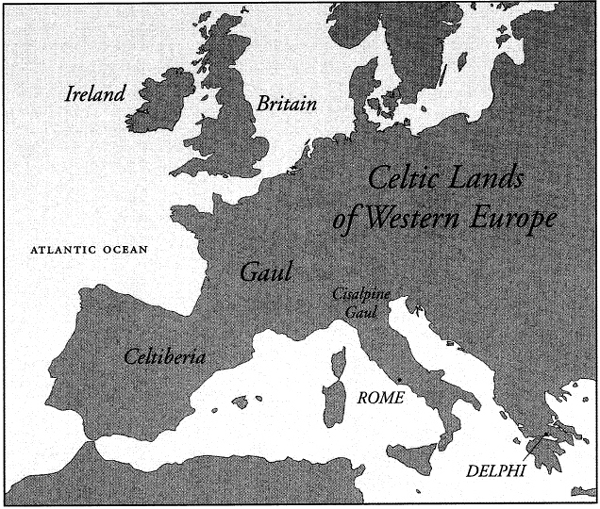

The Greeks and Romans viewed the Celts above all else as warriors par excellence. Very often the first experience any part of the classical world had with the Celts was the terrifying sight of a Celtic army approaching with giant swords drawn and screaming naked warriors leading the way. For the Romans, the Celts were the barbarians who almost destroyed their city in 390 B.C. and the relentless enemy they faced at every turn as they expanded across Europe for the next four hundred years. The Greeks knew them first as the invaders who threatened their homeland in the third century B.C., then as the Galatians who ravaged and eventually settled in nearby Asia Minor. Even when the Celts were finally tamed, they were highly valued as mercenaries in the Greek east and as soldiers in the legions of Rome.

* * *

The earliest source on Celtic warfare is the Greek historian Xenophon writing c. 360 B.C. His two passages on the subject are short and provide no information about Celtic techniques of fighting, but they do show that the Celts were valued mercenary soldiers in the classical world. In this case, Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily, hired Celtic mercenaries and transported them to Greece in 369 B.C. to aid his Spartan allies (Hellenica 7.1.20):

At this time an auxiliary force from Dionysius arrived to help the Spartans. The force consisted of more than twenty ships and carried Celts, Iberians, and about fifty cavalry.

The next year, another group of Celtic mercenaries arrived from Dionysius and helped the Spartans repel a surprise attack with such ferocity that neither the Celts nor their allies suffered any casualties (7.1.31):

The rest were slain while they ran away, many by the cavalry and many also by the Celts.

* * *

A fragmentary inscription from the Acropolis in Athens dated 352/1 B.C. shows that Celtic weapons were valued by the Greeks at an early date. This list of arms dedicated to the goddess Athena includes some of Celtic origin (Inscriptiones Graecae ii2 1438):

Copper helmets from Argos...

261 assorted copper armaments and royal tiaras...

Celtic weapons of iron.

* * *

The fourth-century B.C. philosopher Aristotle mentions the martial qualities of the Celts several times. He first uses the Celts as an example of excess in his famous defense of moderation. He says that an excessive amount of any quality, even bravery, is not desirable (Nichomachean Ethics 3.7):

For the sake of honor, a virtuous man will stand his ground and perform brave deeds. But as we have noted before, there is no name for those who carry this sort of quality to the extreme, being absolutely without fear, not even being afraid of earthquakes or waves, as they say of the Celts.

He also mentions a supposedly widespread custom among non-Greeks of hardening children to adverse weather as training for war (Politics 15.2):

It is a commendable practice to accustom children to the cold from an early age. It is beneficial not only for reasons of health but also in view to future military service. This is why so many barbarian nations, such as the Celts, will dip their babies into cold rivers or give their children little clothing to wear.

Aristotle is also the first classical author to mention homosexual relations among Celtic warriors (Politics 2.6):

The result of ignoring women in law codes is that wealth will be overly desired in such a state, especially if women run things behind the scenes as in most military societies. An exception to this would be those nations which openly approve of sexual relations between men, such as the Celts and certain others.

Next page