This statuette of a bearded and mustachioed Gallic warrior, wearing a torc around his neck (c. 0 BC/AD), was found at St Maur-en-Chausse, Oise, France.

For my sons Tristan and Simon

About the Author

Jean Manco is the author of Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings, published by Thames & Hudson in 2013. This ground-breaking work made accessible to the general reader the revolution in archaeology, historical studies and genealogy now that theories can be directly tested by investigating the DNA not only of living people, but also of those long past.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings

Bog Bodies Uncovered: Solving Europes Ancient Mystery

The Celtic Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends

Exploring the World of the Celts

The Historical Atlas of the Celtic World

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Contents

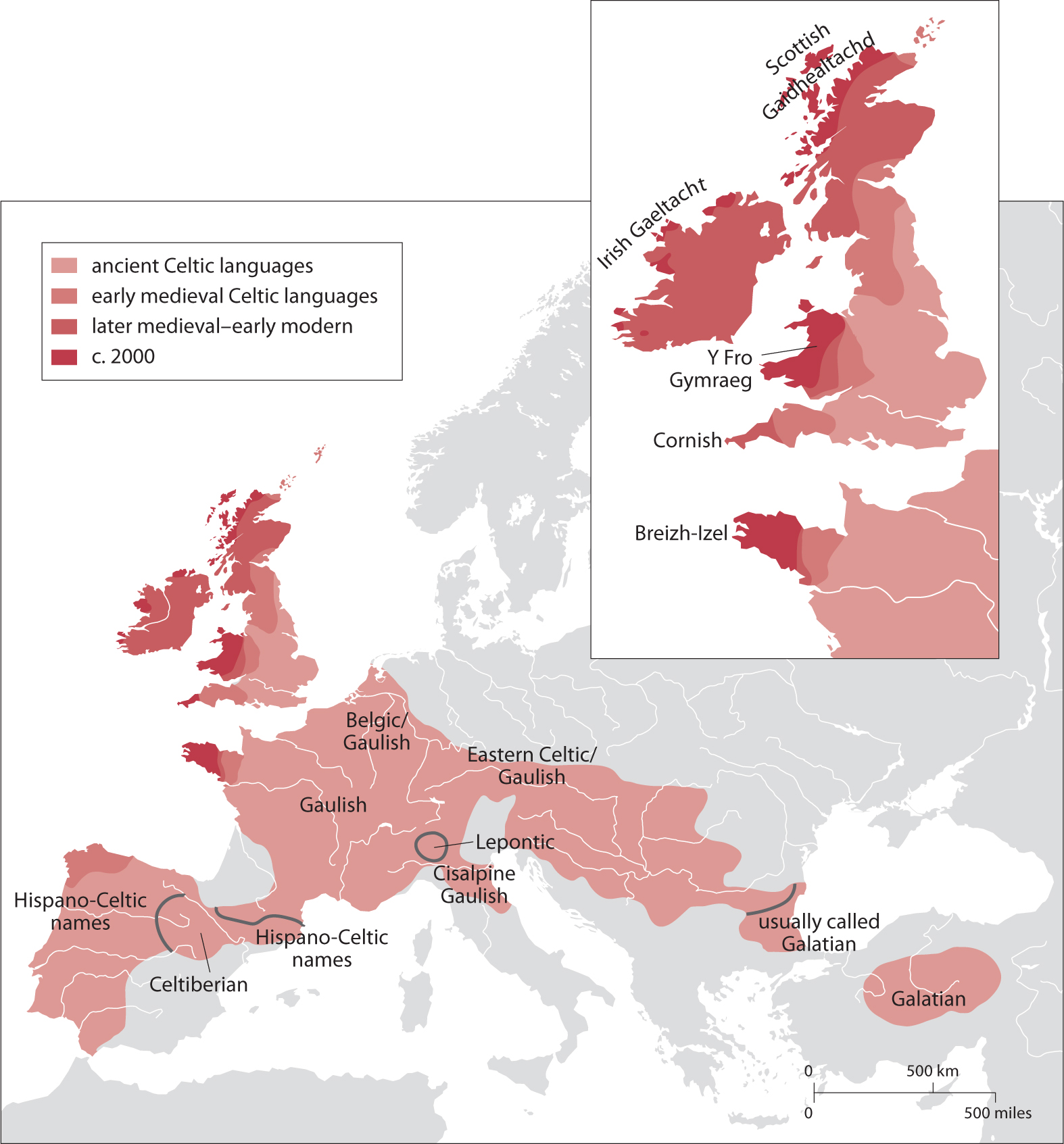

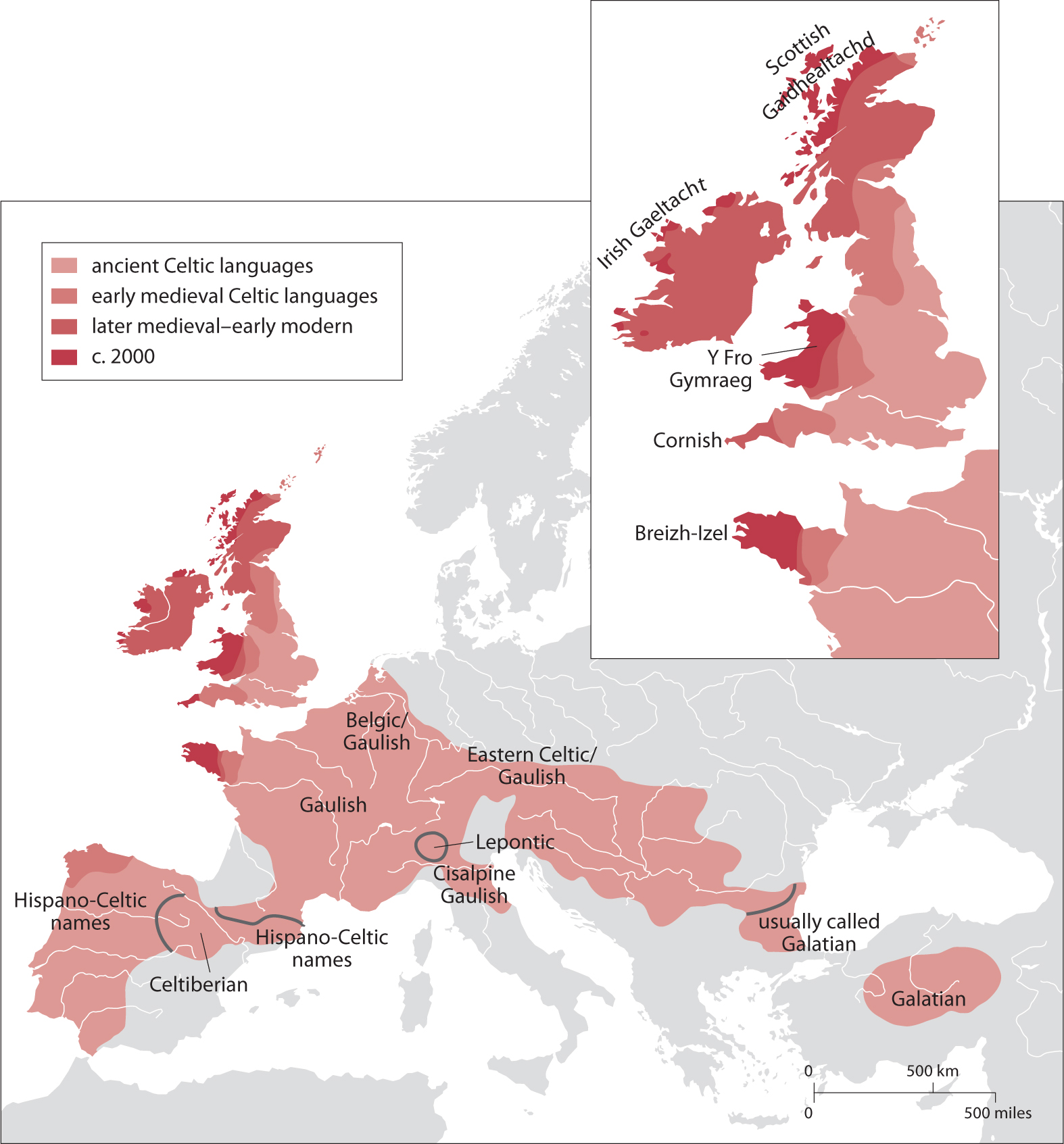

Today Celtic languages cling to precarious life on the northwest fringes of Europe. [] Delve into the pre-Roman past and we find Celtic spoken across the continent. The heritage of the Celts turns up beneath the trowels of archaeologists from Portugal to Romania, from Scotland to Spain.

1 Celtic languages were widespread before most Celtic-speakers were enveloped by the Roman empire. Centuries of Roman rule ensured that the Continental Celts switched to speaking Latin. Celtic languages survived only in the British Isles. The Celtic language of Britain was taken to Brittany by British settlers. Another British settlement in northwest Spain did not long retain its Celtic tongue.

2 The Celtic love of curvilinear design is displayed in this bronze mirror from Desborough, Northamptonshire (50 BCAD 50). It is one of the finest examples of a type of Iron Age object that was exclusively made in Britain. The complex pattern may have been laid out using a compass.

There are many books on the Celts. Their liquid, swirling art fills lavishly illustrated volumes. Works of deep scholarship explore their language and literature. For over a century archaeologists have been triumphantly publishing a wealth of discoveries that can be linked to the Celts. [] Indeed the very enthusiasm in the last century for all things Celtic fed a backlash in the 1990s. A few exasperated archaeologists produced books assuring us that there was no such thing as a Celt or certainly not in the British Isles. Scholars of Celtic studies were unshaken and even more productive. In the first decade of this century an ambitious project by the Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies at the University of Wales culminated in the publication of a five-volume historical encyclopedia of Celtic culture and an atlas for Celtic studies.

Why then is there a need for another book? The fast-moving field of genetics has opened up new vistas on the past. Ancient DNA is replacing argument over who the Celts were and where they came from. At the same time some scholars are taking a fresh look at other kinds of evidence. The traditional conviction that the Celts arose in Iron Age Central Europe has been challenged. Historians meanwhile have been picking apart some of the best-known narratives of that elusive period from the time of St Patrick to that of Kenneth MacAlpin, and weaving their threads together again in new patterns. If revisionism has gone too far in places, it has still ignited fruitful debate. The aim here is to present a new multidisciplinary synthesis, tracking the Celts from their distant origins to their modern descendants through genetics, archaeology, history and linguistics.

Deduced timeline for the prehistory of the Celts

| Approximate date | Archaeology | Language |

| 3400 BC | Yamnaya culture on the European steppe | Proto-Indo-European |

| 31002800 BC | Yamnaya movement up the Danube | Alteuropisch/Old European |

| 22001700 BC | Late Bell Beaker | Early Celtic, Italic and Ligurian |

| 1200750 BC | Bronze Age Hallstatt (Hallstatt A & B) | Celtic |

| 750600 BC | Early Iron Age Hallstatt C | Celtic |

Timeline for the historical Celts

| Approximate date | Archaeological period | Historical event | Date |

| 600-460 BC | Final Hallstatt (Hallstatt D) | Inscriptions in Lepontic (Celtic) began | c. 600 BC |

| Argantonios of Tartessos lived before | 540 BC |

| Hecataeus of Miletus referred to Massalia (Marseilles) as near Celtica | c. 500 BC |

| 460-260 BC | Early La Tne | Herodotus mentioned Keltoi at the head of the Danube and in western Iberia | c. 450 BC |

| Gauls ejected the Etruscans from the Po Valley | c. 400 BC |

| Celtic mercenaries in Greece | 369-368 BC |

| Alexander the Great met a Celtic delegation | 335 BC |

| Celtic incursion into Thrace | 298 BC |

| Gauls entered Asia Minor, where the Greeks called them Galatoi (Galatae in Latin) | c. 280 BC |

| Celtic attack on Delphi | 279 BC |

| 260-150 BC | Middle La Tne | Wars between Attalus I of Pergamum and the Galatians of Asia Minor | 233-232 BC |

| Roman victory over the Boii, Insubres and Gaesatae in Italy | 225 BC |

| Start of the Roman conquest of Iberia | 218 BC |

| Final defeat of the Cisalpine Boii | 191 BC |

| 150-50 BC | Final La Tne | Founding of the Roman Provincia Gallia Narbonensis in southern Gaul | 125 BC |

| Caesar conquered the remainder of Gaul | 58-51 BC |

| Caesar made two sorties into Britain | 55-54 BC |

| AD 43-410 | Romano-British | The Roman conquest of Britain | AD 43-84 |

| End of Roman Britain | AD 410 |

| AD 410-800 | Early medieval | Death of St Columba | AD 597 |

Another Roman author describes the Gauls as very tall, with white skin and blond hair, which is exactly the way other Classical authors portrayed the Germani. As MacNeill pointed out, what would most strike a Roman observer in northern Europe would be a higher percentage of paler colouring than he saw in Italy. Seizing on what is actually a matter of degree, stereotypes were created. We are still prone to this today. So it needs to be said that what MacNeill surmised in 1920 we can now prove. He felt that all the present nations of Europe are a mixture of the same ancestral components in varied proportions. He was right. As we shall see, there are three main components to the modern European gene pool. They came from ancient hunter-gatherers, early farmers and a Copper Age people. The modern Irish have a mixture of all three, as do the modern Germans and Italians. Any genetic differences are far too subtle to talk in terms of a Celtic race.

Next page