St. Patrick of Ireland: A Biography

SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 2006 by Philip Freeman

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON& SCHUSTERand colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Karolina Harris

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Freeman, Philip, 1961

The philosopher and the Druids : a journey among the ancient Celts / Philip Freeman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

1. Civilization, Celtic. 2. PosidoniusTravel

Europe. 3. EuropeDescription and travel. 4. EuropeHistoryTo 476. I. Title.

D70.F73 2006

913.6043dc22

2005054150

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-8906-1

ISBN-10: 0-7432-8906-4

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

Acknowledgments

IM DEEPLY GRATEFUL to those who made this book possibleespecially the teachers who introduced me to the world of Posidonius. I first heard this philosophers name many years ago when I was an undergraduate and had the pleasure of studying Greek civilization under Professor Peter Green. While I was a graduate student, Professor John Koch pointed me toward the scattered passages of Posidonius as an amazing source of early Celtic history. Many others since then have aided me immeasurably in my own explorations of the Celts in the classical worldI offer special thanks to Barry Cunliffe, Joseph Eska, Patrick Ford, James Mallory, Gregory Nagy, Joseph Nagy, and Christopher Snyder.

I was honored to be selected as a Visiting Scholar at the Harvard Divinity School during 20045, which provided an unparalleled setting and resources for research. My home institution of Luther College in beautiful Decorah, Iowa, was gracious in allowing me to take advantage of this wonderful opportunity.

Jolle Delbourgo, Bob Bender, and Johanna Li all patiently led me through the publication process. But my greatest thanks are to my wife, Alison, who makes all things possible.

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Celticis a magic bag, into which anything may be put, and out of which almost anything may come. Anything is possible in the fabulous Celtic twilight.

J. R. R. TOLKIEN

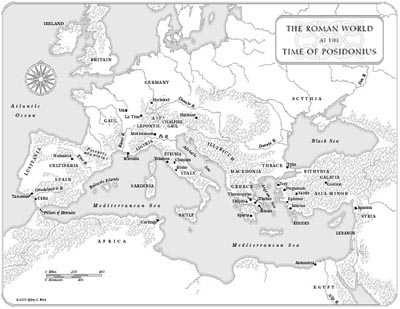

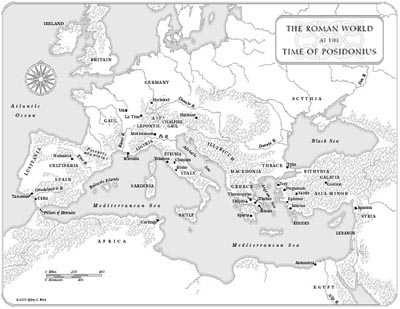

ONE WARM SUMMER DAY in the year 335B.C. , a young Alexander the Great was sitting outside his tent on the banks of the Danube River. His father, Philip of Macedon, had been murdered just the year before during a wedding, but Alexander had lost no time in seizing his fathers throne and firmly establishing his own rule throughout Macedonia and Greece. Philip had long nursed a dream of invading the mighty Persian Empire to the east, a vast kingdom stretching from the borders of Greece to Syria, Egypt, Babylon, and all the way to India. Alexander shared this vision and prepared for the upcoming Persian campaign by securing his northern frontiers against the wild tribes of Thracians and Scythians who rode south to raid and pillage whenever they saw an opportunity.

Alexander had just defeated these fearsome warriors of the north in battle using the legendary daring and determination that would soon gain him the largest empire the world had ever known. But on this day the twenty-one-year-old Macedonian general and former student of the philosopher Aristotle was content to rest from war and enjoy the glow of victory with his companions. Among them was a young man named Ptolemy, a childhood friend of Alexander who now served as a trusted lieutenant. Twelve years later, after Alexanders death, Ptolemy would seize control of Egypt and establish a ruling dynasty that would end with his descendant Cleopatra.

Ptolemys memoir records that as Alexander sat before his tent, a small group of warriors approached the camp and asked for an audience with the king. They were unusually tall men with drooping mustaches, each wearing a gleaming gold torquea sort of thick necklacearound his neck, and a brightly colored tunic that reached halfway to his knees. They carried long swords in finely decorated scabbards attached to chain belts, while flowing cloaks of checkerboard green were fastened around their shoulders with enormous gold brooches. Strangest indeed to the eyes of a civilized Greek was the utterly barbaric way they dressed below the waistthey wore, of all things, pants.

The embassy approached the astonished King and presented themselves as Celts who had traveled from the mountains of the west to seal a pact of goodwill with the victorious monarch. Alexander welcomed them warmly, assured them of his peaceful intentions toward their people, and invited them to share a drink of fine Greek wine. The Celts gladly accepted, though they refused an offer to dilute the wine with water as was the Mediterranean custom. Aristotle had taught Alexander never to pass up an opportunity to discover something new about the world, so the young general eagerly inquired about Celtic culture, history, and religion. Finally, when their tongues were thoroughly loosened by drink, Alexander asked his visitors one last question: What do you fear the most? Most men in such a situation would naturally have turned to flattery and quickly answered that they most feared the military might of the great general who sat across from them. But the leader of the Celtic band soberly looked Alexander in the eye and said, Nothing. We honor the friendship of a man like you more than anything in the world, but we are afraid of nothing at all. Except, he added with a grin, that the sky might fall down on our heads! The rest of the Celtic warriors laughed along with their leader as they rose and bade farewell to the Macedonians. Alexander watched them stride out of camp and begin the long trek back to their mountain home. He then turned to his friends and exclaimed, What braggarts these Celts are!

This meeting between Alexander and the Celts was one of the earliest encounters between the Greeks and an almost legendary people who lived in the unexplored forests and mountains of western Europe. The few Greek records of the Celts before Alexanders time speak only of a wild and uncivilized collection of tribes known as the Keltoi , who dwelled in the distant lands of Italy, Spain, and beyond the Alps, all the way to the mysterious northern sea. But the Celts were rapidly becoming a force in the classical world. In the decades before Alexander, they had swept south over the alpine passes and breached the gates of Rome. Fifty years after Alexander, they would attack the sacred Greek site of Delphi, home to Apollos oracle, and cross the Hellespont into Asia Minor, ravaging the coast before settling permanently in their own kingdom of Galatia in the middle of the Greek world. From that time to the end of the Roman Republic, the Celts would be a constant threat to the civilized lands of the Mediterranean. Only with the crushing defeat of the Gauls by Julius Caesar in the first centuryB.C. would the Celts virtually disappear from the stage of history.