I am grateful to Margaret (many times over) and to all my other first readers: Kate Harvey and Starling Lawrence; Gill Coleridge and Melanie Jackson; Nicholas Blake and Kris Doyle; Stephen Roberts; and my guide to ancient Greek, Gerald Sgroi. Thanks also to Paul Baggaley, Nick Brown, Wilf Dickie, Stephen Edwards, Camilla Elworthy, Ryan Harrington, Sam Humphreys, Sophie Jonathan, Cara Jones, Laurence Laluyaux, Drake McFeely, Jenny Preston, Elizabeth Riley, Peter Straus, Isabelle Taudire and Katie Tooke, and to the following institutions: the Bibliothque Nationale de France, the British Library, the British Museum, the Centre archologique europen (Bibracte), Cumbria Woodlands, the Hunterian Museum (Glasgow), the Mairie de Paris, the Muse dArchologie mditerranenne (Marseille), the Muse darchologie nationale (Saint-Germain-en-Laye), the Muse mile Chenon (Chteaumeillant), the National Museum in Prague, the National Museum of Denmark, the National Museum of Scotland, Parc Samara, Stanfords map shop, Tullie House Museum (Carlisle), and, in Oxford, the Ashmolean Museum, the Bodleian Library, Exeter College, Linacre College, the Sackler Library, the Social Science Library, the Taylor Institution Library, the Vere Harmsworth Library and the Oxford University Parks.

BALZAC

VICTOR HUGO

RIMBAUD

STRANGERS

Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century

THE DISCOVERY OF FRANCE

PARISIANS

An Adventure History of Paris

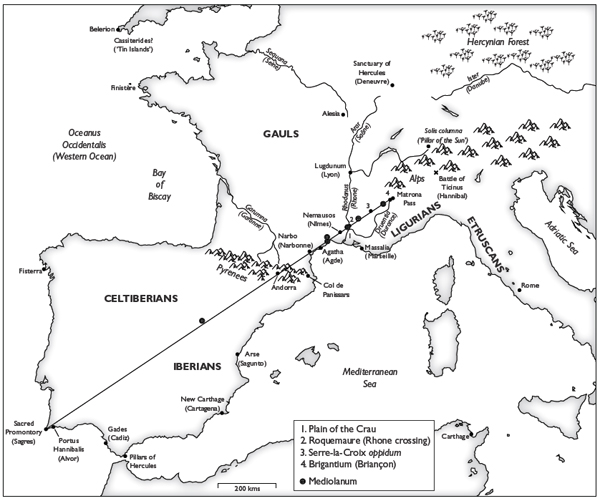

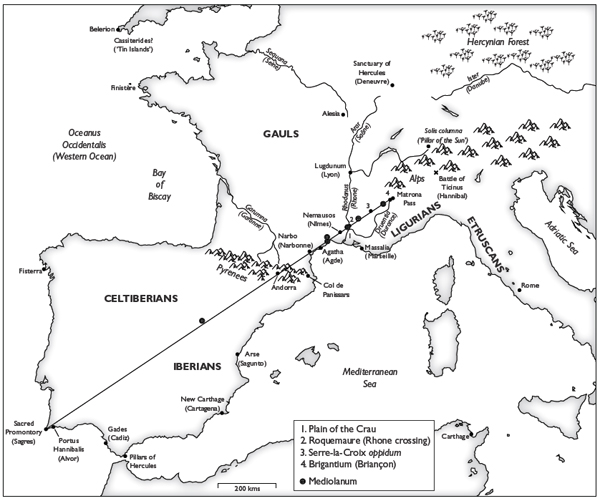

For many centuries, the Celts were a mystery to their neighbours. In the sixth century BC, the Greeks had heard from intrepid merchants following the tin routes or from sailors blown off course of a people called the Keltoi, who lived somewhere along the northern shores of the Mediterranean. In the early fifth century, when the historian Herodotus tried to shine a light on this distant world, he was like a traveller on a starless night holding up a candle to the landscape. Of the Celts, he had been told the following: they live in the land where the Danube has its source near a city called Pyrene, and their country lies to the west of the Pillars of Hercules, on the borders of the Cynesians, who dwell at the extreme west of Europe. This was either fantastically inaccurate (the supposed homelands are nearly two thousand kilometres apart) or an over-condensed version of an amazingly accurate source. Celtic tribes are known to have existed at that time both in the Upper Danube region and in south-western Iberia.

The Pyrenees confused by Herodotus with a fictitious city called Pyrene lie almost exactly halfway between the two. They form a great barrier across the western European isthmus, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea, dividing France from Spain. Most of the trans-Pyrenean traffic crossed at either end, where the mountains tumble down to the sea, but the central range was surprisingly porous. In the early Middle Ages, the road that leads to the principality of Andorra was used by smugglers, migrant labourers and pilgrims bound for the shrine at Santiago de Compostela. The snowy passes of the Andorran Pyrenees lie on the watershed line, from which the rivers flow either west to the Atlantic or east to the Mediterranean. In the days of the ancient Celts, this was the home of a tribe called the Andosini, who entered history when they were defeated by Hannibal in 218 BC during his long march from Spain to Italy. No one knows for certain how the Carthaginian general came to encounter such a remote tribe, but ancient history sometimes hinges on a place that seems desolate beyond significance.

1. The Road from the Ends of the Earth

The Celts own stories of their origins were told over an area so vast that the sun spent an hour and a half each day bringing the dawn to it. Because the Celts were a group of cultures, not a race, they spread rapidly from central Europe, by influence and intermarriage as much as by invasion, until the Celtic world stretched from the islands of the Pritani in the northern sea to the great plains east of the Hercynian Forest, which even the speediest merchant did not expect to cross in under sixty days. As a result, although the tales were told in dialects of the same language, they took many different forms, like trees of the same species rooted in different soils and climates.

One tale in particular was considered pre-eminent and true, since it described what appeared to be a real journey made by a founding father of the Celts. It survived in various fragmented forms; some of the incidents became detached from their original context or were too strange to be part of a coherent narrative; yet they were held together by the geography of half a continent. The journey began at the extreme western tip of Europe the Sacred Promontory, where a temple to Hercules stood above the roaring sea in a place so holy that no one was allowed to spend the night there. But it was in the mountains between the two seas that the hero entered the country known as Gaul. And since Gaul is the heartland of the first part of this adventure, this is where the story of Middle Earth begins.

With the mists of the Western Ocean draped over the pine forests, it would have been easy to imagine the scene: the smoke climbing up through the trees, the crackle of branches, and the fire, as red as a lions mouth. Cattle were stumbling down the riverbeds to the hot plains below. The man knew the route they would take. From the ends of the earth, where the sun and the souls of the dead plunge into the sea, he had followed rather than driven them, so that it was not entirely true to say that he had stolen the herd. He acted out of desires that were foreign to his mind but not his body. It was in the country of the Bebruces, at the time of year when the sun rises and sets in the northern sky. The daughter of King Bebryx had served him bread, meat and beer in the great wooden hall, and when the sun had returned to the lower world she had taken him to her bed, and he had filled her with the seed of a gods son until the great hall shook and the walls of her chamber were beyond repair.

He had left the hall like a god or a thief. But the part of him that was human was stung by his act of abandonment. He thought of the creature like a snake that was growing inside her; he thought of her shame and of a fathers rage. He had stopped where the cork oaks and the olives begin. He strode back up into the green, dark mountains, towards the ridge he had dented and levelled with his feet. Her white limbs lay scattered on the ground as though they had lain together on the pine needles and she had been dismembered by the force of his love. He gathered up the remains of the wolves feast. Her blood, and the blood of a gods strange grandchild, burned his hands. He thundered her name to the skies that he had once held aloft the Greek-named daughter of a Celtic king. Her name meant fire, a gem, or the gold grain of the harvest. He felled a forest, then another. Rivers that had yet to be named began to flow from the bare mountain tops. He built a pyre that the midday sun would light. The smoke would be seen from the Ocean, where sailors hugged the coast in boats of skin; then the wind would carry it across the isthmus to the safe, thronged harbours of the Middle Sea, and even that blazing range of peaks would be unworthy of his Pyrenea.

He caught up with the cattle in the salty plain. He walked behind them in a straight line, carrying his club, the lion skin slung over his shoulder. In his other hand, he carried a wheel, divided into eight sections by its spokes. He paused where the cattle stopped to drink, at a ford or a spring at the foot of a hill. There were rough stones at his feet, shaped only by torrents and volcanoes, but behind them, on the path the man and the animals were trampling out, along with the rich gift of dung, there were sherds of brick and pot, cut stones flushed with cinnabar, ingots of tin and even gold. Keeping the land to his left, he walked beside the lagoons of the Middle Sea. Sometimes, there was a stone watchtower and a sail on the grey horizon. At dawn, by the shivering inlets, the sun rose again in the northern sky and burned a beacon onto his eye. In the warm nights, he angled his stride by the blurry trail of stars where the sun had passed or where his stepmother, tricked while she slept into giving the misbegotten mortal her breast, had wasted her milk in angry ostentation.

Next page