Campaign 69

Nagashino 1575

Slaughter at the barricades

Stephen Turnbull Illustrated by Howard Gerrard

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

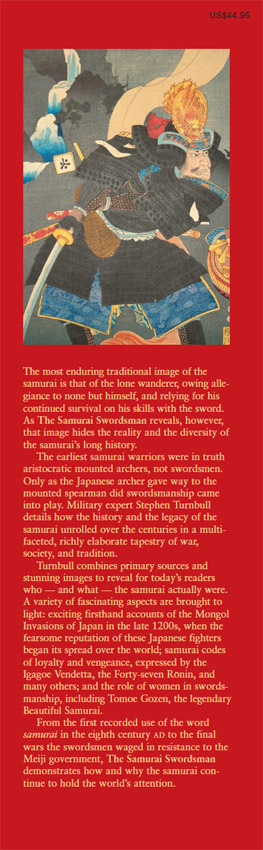

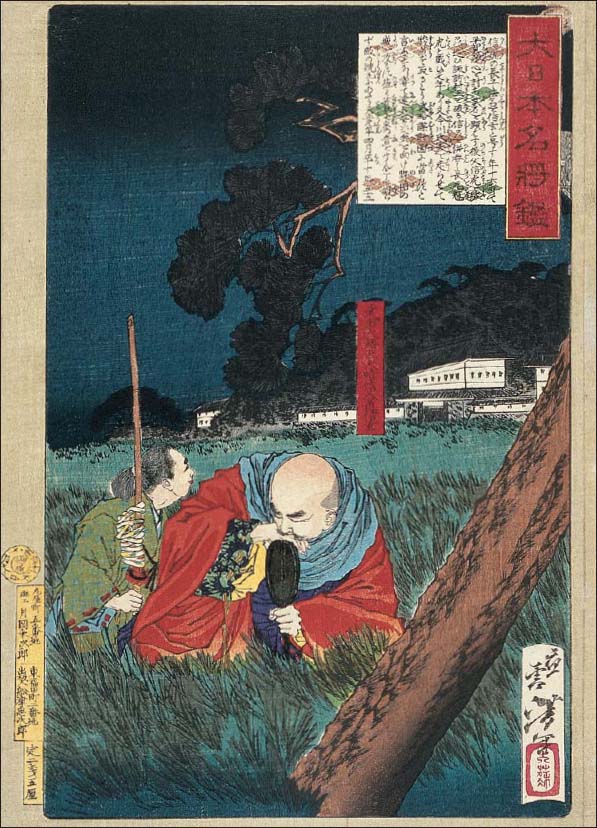

This print by Yoshitoshi shows the moment when Takeda Shingen was mortally wounded by a bullet fired by a sentry during the siege of Noda castle in 1573. His death proved to be a tragedy for the Takeda family, when the leadership passed into the hands of his less talented son, Takeda Katsuyori. The depiction of the walls of Noda as a simple yamashiro style castle are not unlike the appearance Nagashino castle would have had in 1575. (Courtesy of Rolf Degener)

ORIGINS OF THECAMPAIGN

Nagashino and the Warring States Period

T he siege of Nagashino castle and the battle of Nagashino which followed it make up one of the pivotal moments in the history of the samurai. Its military significance is considerable, because it demonstrated the power available through a skilful combination of arms, comparatively simple defensive measures and, above all, the use of firearms on a large and controlled scale. Other samurai leaders who later found themselves in a similar position would look for lessons that they could apply from the example of Nagashino.

The battle of Nagashino is but one among many conflicts of 16th century Japan. The period is known as the Sengoku-jidai (Warring States Period), a term borrowed from the Chinese dynastic histories. For the past five centuries Japan had been ruled by a succession of dynasties of Shoguns, the military dictators who ruled on behalf of an emperor who since 1185 had been reduced to the position of a figurehead. The Shogunates suffered many vicissitudes during those years. There had been attempts at imperial restoration, conflicts within ruling houses, and one episode of foreign invasion. However, until the mid-15th century the institution of the Shogun, which at that time was vested in successive generations of the Ashikaga family, still managed to control and govern the country.

The tragedy for the Ashikaga happened in 1467, when a civil war, known as the Onin War from the traditional year in which it occurred, began to destroy Kyoto, the capital city of Japan. As the ashes settled the fighting spread further afield, setting in motion sporadic conflicts that were to last for 11 years. Some semblance of order was finally restored, but not before many samurai generals had realised that the Ashikaga Shogunate was gradually losing its power and authority, and that if the samurai wished to increase their land holdings by the use of force against their neighbours, then there was little likelihood of any intervention from the centre to stop them. Thus over the next 50 years Japan slowly split into a number of petty kingdoms, ruled by men who called themselves daimy (great names). Some had held lands in their regions for centuries, and had increased their power by the readiness of neighbours to ally themselves to a powerful protector. Others seized power by murder, intrigue or invasion, and held on to that power by military might.

It would be a mistake to look upon the daimy of the early 16th century as bandit leaders. In many cases their lands were well governed, and the men who worked in their rice fields, nearly all of whom were part-time soldiers, showed their overlords a degree of loyalty that the Ashikaga Shoguns would have envied. Such loyalty was expressed through willing and enthusiastic military service, carried out on the daimys behalf when a call to arms was issued. It was said of the followers of one daimy, the Chsokabe of Shikoku Island, that these farmer-samurai were so ready to fight that they tilled the rice-paddies with their spears thrust into the ground at the edge of the field and their sandals tied to the shafts.

As the Sengoku-jidai wore on it was inevitable that smaller daimy territories should be swallowed by bigger ones, until by about 1560 Japan consisted of a number of major power blocs, alternately in alliance or in conflict as the balance of power shifted from one lord to another. In the midst of it stood the Shogun, impotent in military terms but immensely powerful as a symbol. By ancient convention no one could become Shogun unless he possessed the appropriate lineage back to the original Minamoto family an honour enjoyed by the Ashikaga. The secret to controlling Japan, therefore, was control of the Shogun.

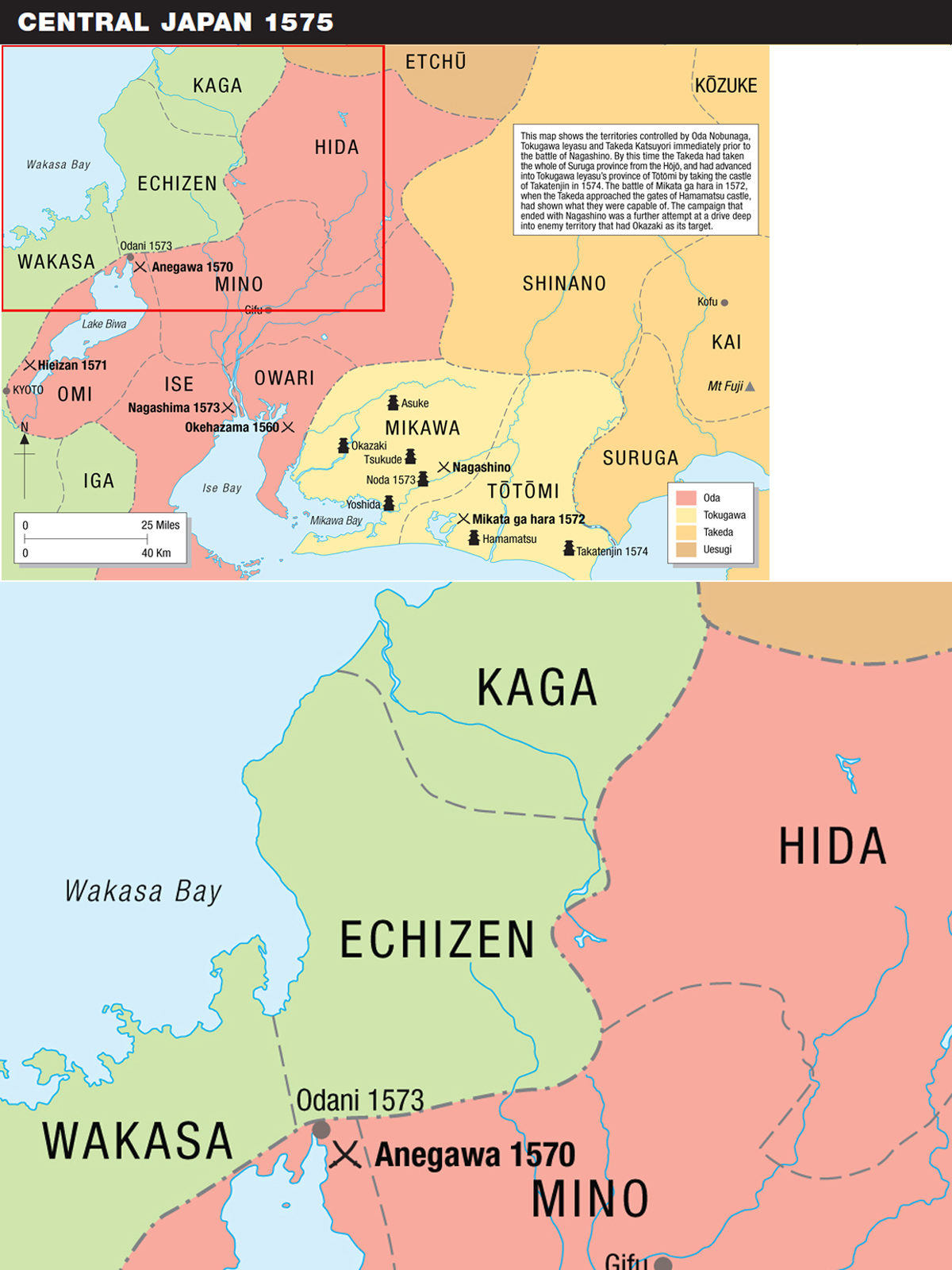

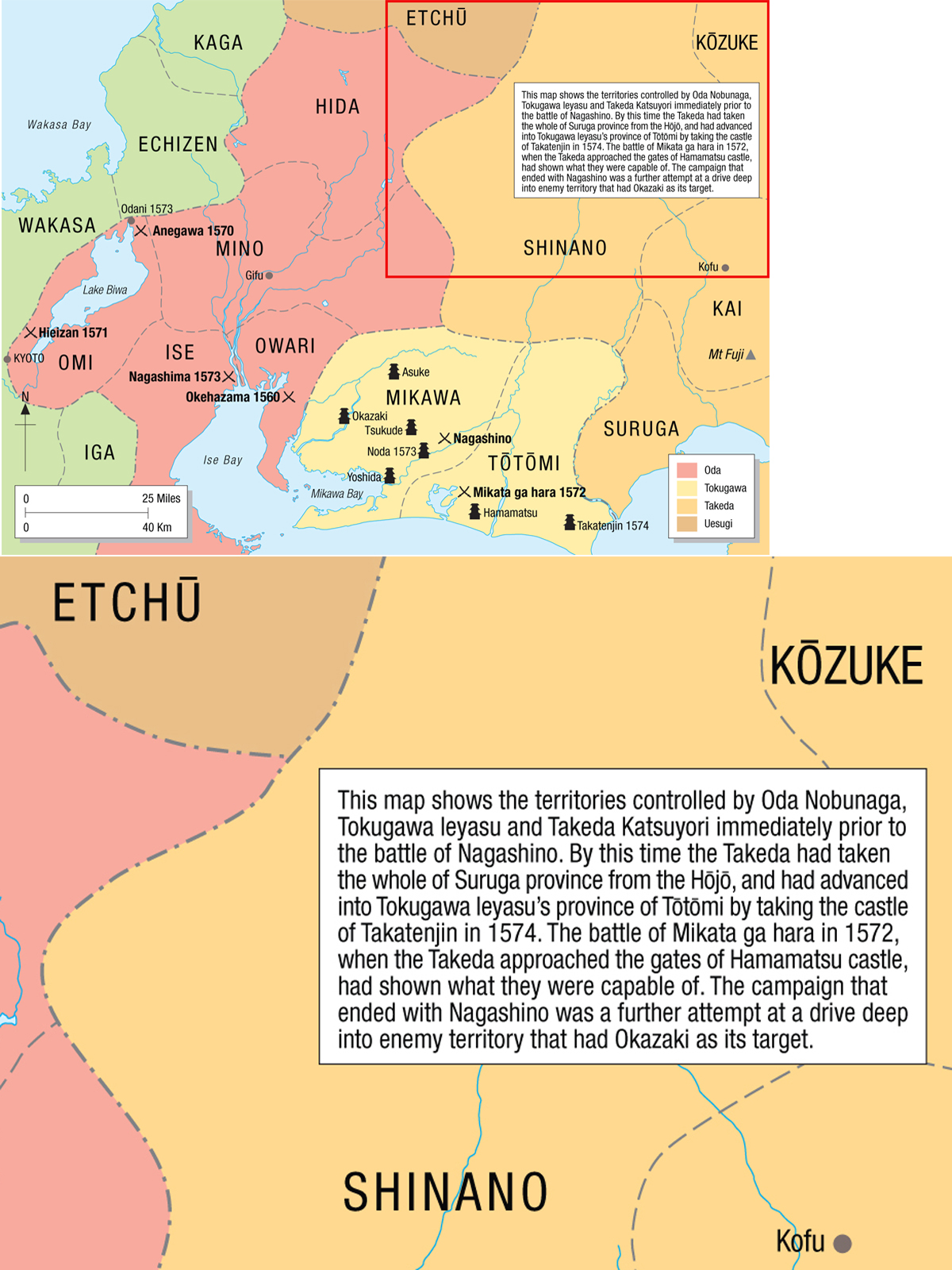

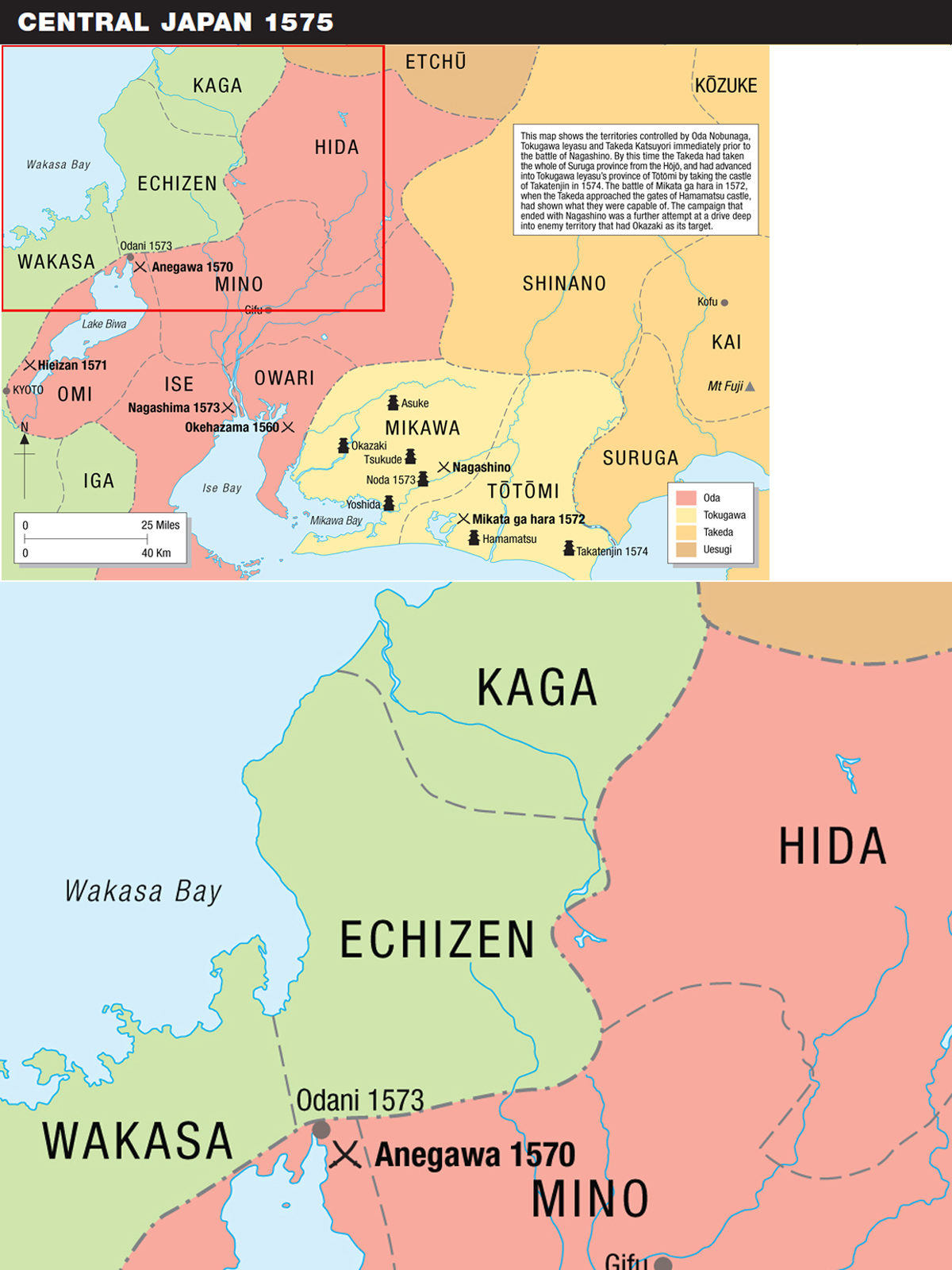

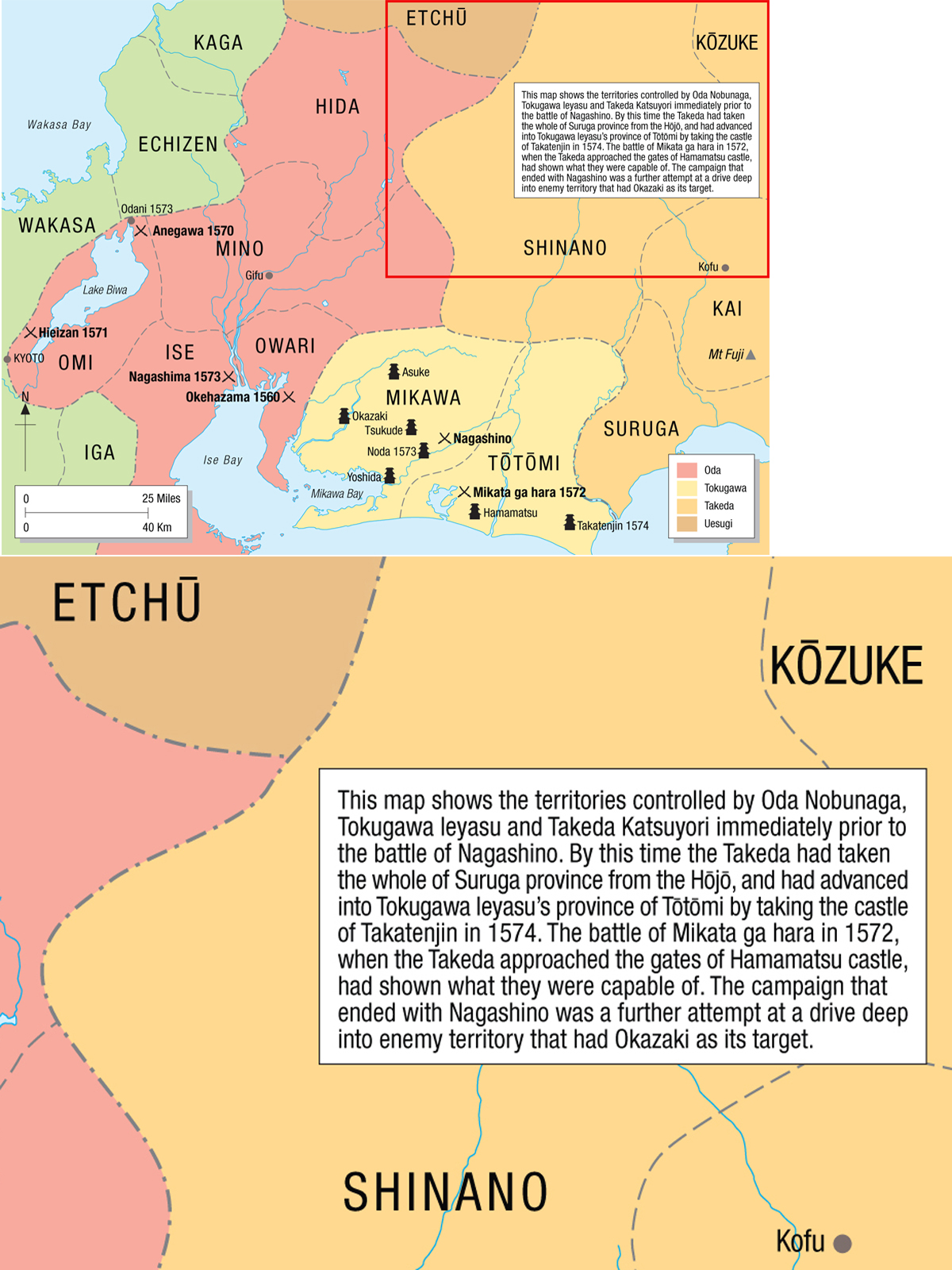

In 1560 a decisive point was reached when a powerful daimy called Imagawa Yoshimoto planned to march on Kyoto and set up his own puppet Shogunate. The first obstacle Imagawa had to overcome was a neighbour called Oda Nobunaga, whose much smaller territory was inconveniently situated between Imagawa and his goal. Full of confidence, the Imagawa army moved into Owari province, where they were unexpectedly and thoroughly defeated. Oda Nobunaga launched a surprise attack on them and succeeded in spite of odds of 12 to one against him. This victory, the battle of Okehazama, flung Oda Nobunaga into the big league of daimy. His military prowess and his convenient location not far from the capital ensured alliances and support, not the least of which was a long-standing association with the ruler of neighbouring Mikawa province, Tokugawa Ieyasu, formerly a retainer of the Imagawa but freed from that obligation by the victory at Okehazama.

The two red banners of Suwa Myjin, the deity of the area where the Takeda were based, treasured by the Takeda along with the Sun Zi flag, and were carried into battle together with the blue flag. They bear invocations of the god in Japanese characters, while round the edge of the larger one is a religious incription in Sanskrit.

For the next 15 years Oda Nobunaga fought battles, made marriage alliances, arranged coups and built castles, until in 1568 he himself was able to enter Kyoto in triumph with Ashikaga Yoshiaki, whom he proclaimed Shogun. More battles and campaigns followed, among which there began a long and bitter struggle between the Oda and the Buddhist fanatics of the Ikk-ikki, whose well trained fighting men were the equal of any daimys army.

In spite of having control of the Shogun, Oda Nobunaga still effectively ruled only a handful of provinces around the capital in central Japan, and some very powerful enemies lay just over the horizon. To the west were the Mori, who controlled the Inland Sea, to the north were the Uesugi, and to the east were the mighty Takeda, under their daimy, Takeda Shingen.