Campaign 40

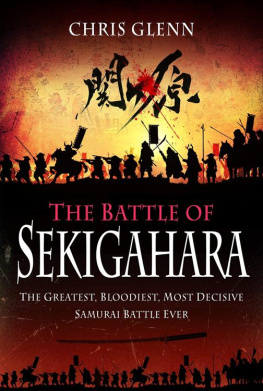

Sekigahara 1600

The final struggle for power

Anthony J Bryant

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

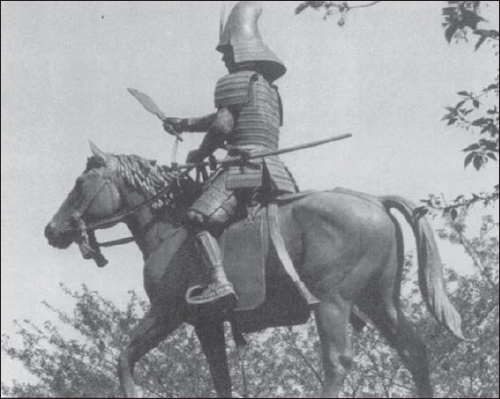

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598), the great unifier, built an empire the stability of which he could not guarantee for his five-year-old heir. His death in 1598 left the nation under the control of two five-man councils that were unable or unwilling to cooperate to see the late unifiers wishes come true. Several of his foster sons would participate in the battle at Sekigahara, and one Kobayakawa Hideaki would betray his cause. (Nakamura Park, Nagoya)

THE ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

T oyotomi Hideyoshi was dead. The great unifier had been able to do what few before him had done. He had taken a nation embroiled in intrigues and civil war, and one by one brought all the warring clans under his control.

Hideyoshi had begun his grand conquest by picking up the pieces of the hegemony of his own slain lord, Oda Nobunaga, claiming guardianship of the latters young son, and starting to make alliances and expand his influence. His actions alienated many of Nobunagas old vassals, and Hideyoshi was forced to make war on his erstwhile comrades; those who would not freely ally with him and acknowledge him as their lord felt the wrath of his army.

Even Tokugawa Ieyasu, one of the most powerful feudal lords in Japan, finally joined Hideyoshis banner. Though Ieyasu might eventually have defeated Hideyoshi, he decided the more certain path was alliance and patience.

Despite all the attempts of fawning contemporary biographers, who tried to tie him to the ancient Fujiwara clan, Hideyoshi had been born of peasant stock, and there was no way he could claim the title of shgun. He had to settle for the office of kanpaku, a civil prime minister, but was, nevertheless, the undisputed master of Japan, and his word could be backed up with an army, just as any shguns would.

By the 1590s the ageing hegemon wanted an heir to succeed him, so in 1592 he transferred the position of kanpaku to his adopted son, Hidetsugu, and took for himself the title taik (used by retired kanpaku), by which he is commonly known.

Japan was at peace for the first time in decades, and Hideyoshi like Arthur in a too-successful Camelot saw and felt the stirrings of his underlings for some military glory. His allies and vassals were battle-hardened veterans, and they had the egos and ambitions in keeping with their experiences.

Hideyoshi decided to launch a campaign to conquer China, with the intermediate goal of gaining control of Korea. As ambitious as the project was, it was met with considerable enthusiasm from most of his vassal lords. In 1592 a flotilla sailed to Korea with 130,000 samurai. The Japanese met with several initial successes, but when a Chinese army poured across the border to help the fleeing Korean king, the situation changed. Hideyoshi sent another 60,000 men to support their positions, and the stalemate began.

Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) was long since dead, but it was his efforts at establishing unity that had set the stage for Hideyoshi to come to power. With Hideyoshi dead, a power vacuum had to be filled. This statue, on the grounds of Kiyosu Castle, shows the warlord in a full suit of densely laced armour. His assassin, Akechi Mitsuhide, was the father of Christian convert Hosokawa Gracia, the wife of Hosokawa Tadaoki, one of Ieyasus most loyal general-retainers.

When a son, Hideyori, was born to the taik in his fifty-seventh year (in 1593), relations soured with the kanpaku Hidetsugu three years later, the deposed Hidetsugu was invited to commit seppuku, ritual disembowelment, for some perceived plot against his adoptive father and former sponsor.)

The problems at home distracted Hideyoshi from the Korean campaign, and he sent an embassy to China to discuss terms for peace. The embassy finally returned in 1596 with an unacceptable reply from the Chinese emperor. Hideyoshi was angered at this refusal, and even more upset that the Chinese emperor was willing merely to invest him with the title of King of Japan, which would make him, in essence, a vassal of the Chinese emperor (to say nothing of making him guilty of an act of lse majest against the reigning Japanese emperor, from whom Hideyoshi held his position).

The next year Hideyoshi responded by sending 100,000 more men to Korea under the command of his wifes nephew (another adopted son), Kobayakawa Hideaki, who was all of 15 years of age. Plagued by conflicting egos within and disease without, the expedition was doomed to failure.

In May 1598 Hideyoshi fell ill. Fearing for his sons safety (and anxious to protect his inheritance), the taik called together his most powerful and wealthy vassals: Tokugawa Ieyasu, Maeda Toshiie, Uesugi Kagekatsu, Mri Terutomo and Ukita Hideie. None of them was worth less than a million koku a year. (One koku, a unit of measure representing approximately 180 litres of rice, was how wealth was measured in feudal Japan: it was the amount of rice believed necessary to keep a man alive for a year.) Hideyoshi made them swear to support the five-year-old Hideyori in his position, and to treat the boy as if he were Hideyoshi himself. To Maeda Toshiie and Tokugawa Ieyasu the taik entrusted the care and raising of his son, though Toshiie would be the actual physical guardian. The lords agreed, and thus became the five tair, a council of regents.

These regents were to work side by side with the five commissioners (bugy) Hideyoshi had earlier appointed to oversee government of the capitol. Together they were to run the country in Hideyoris name until he came of age.

The taik also ordered that the armies be recalled from Korea. This split his vassals into two camps, one camp thought victory could be taken, and didnt want to return, while the other was more than willing to quit the campaign. When those favouring withdrawal began to do so, the others had no choice but to follow, since their positions quickly became untenable.

This served to create enemies among the bugy, for many would remember the withdrawal forced on them, and their resultant loss of face.

Then, on 15 September, 1598, Hideyoshi died.

In order to better protect his own interests, Ieyasu installed himself in Fushimi Castle, the late Hideyoshis personal fortress, and was viewed by the other members of the council as a potential usurper. However true this accusation may have been, Hideyori, at the age of five, was scarcely in a position to govern. Maeda Toshiie, in residence in saka Castle with Hideyori, grew concerned.

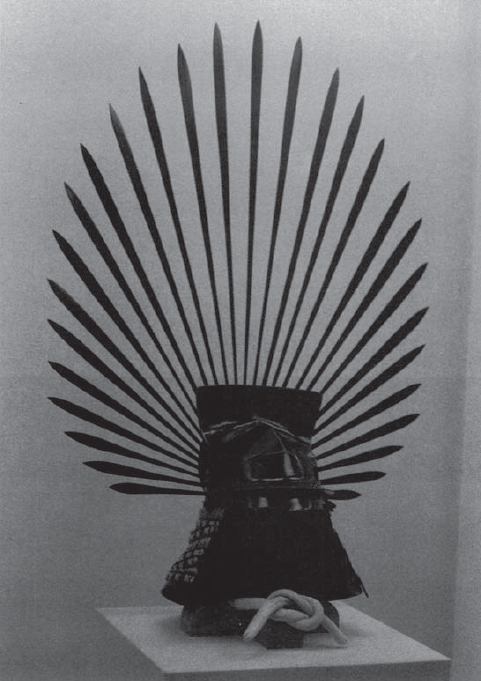

Hideyoshis helmet is one of the most recognisable in all Japanese history. The large rays emanating from the back are supposed to represent the sun. (Kat Kiyomasa/Toyotomi Hideyoshi Museum)