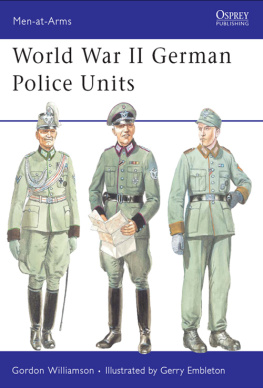

Men-at-Arms 434

World War II German Police Units

Gordon Williamson Illustrated by Gerry Embleton

Series editor Martin Windrow

CONTENTS

WORLD WAR II GERMAN POLICE UNITS

INTRODUCTION

T HE POLICE HAD ALWAYS HAD a respected status in German society. This may in part have been due to the fact that German policemen had traditionally been recruited fairly heavily from among former soldiers, and even before the advent of the Nazis were a paramilitary rather than a purely civilian force.

Heinrich Himmler, the Reichsfhrer-SS, held the newly created post of Chef der Deutschen Polizei from April 1934. He spared no effort to ensure that the SS controlled directly or indirectly every important policing function in the Third Reich, to the extent that eventually even the most humble Police functionary carried an SS paybook.

After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles had limited Germany to an army of 100,000 men, which resulted in huge numbers of wartime soldiers being thrown into unemployment. There were no such restrictions on the size of the police forces, however, and considerable numbers of former soldiers simply moved from one uniformed service to another. Under the precarious conditions of the Weimar Republic, when the greatest threat to the authority and integrity of the state was perceived as coming from the Communist movement, the government was quite happy to see the police strengthened by an influx of such men, who tended to hold authoritarian views about societys overriding need for order. The military also saw the benefit of keeping large numbers of trained and disciplined men within the control of an organ of the state, providing a cadre who might at some future date be transferred back to the authority of the armed forces.

Inevitably, when the Nazis came to power at the end of January 1933, they were happy to continue with this expansion and militarization of the police. For years they had been quietly infiltrating the police forces of the various German states or Lnder, and many Nazi Party members were already in senior positions. Now these officers were empowered to begin combing out policemen whom they felt to be politically unreliable, and any with known democratic sympathies were ousted. Almost immediately after the Nazis came to power, members of the police were seen wearing the Partys swastika armband on their uniforms.

The police structure at this point was still organized on a state-by-state basis. In Hitlers first cabinet, Hermann Gring was appointed as chief (President) of the Prussian Police, thus gaining control of the largest and most influential of such forces. Within weeks, Department IA of the Prussian Landespolizei had been completely purged of any suspect elements, and its Amt III was retitled as the Geheime Staats Polizei the Secret State Police or Gestapo.

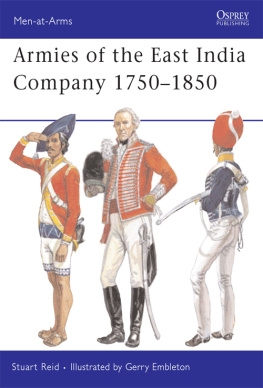

A member of a Landespolizei force, wearing an M1916 steel helmet and a uniform dating from before the unification of the police forces; note the star badge on his belt buckle, and the absence of a Police national emblem on the left sleeve. Many of the German states had their own unique police uniforms and insignia, which would be swept away when the new grey-green national uniform was introduced in the mid-1930s. (Josef Charita)

The numbers of police available to the government in Berlin were quickly doubled by Grings creation of the Prussian Hilfspolizei or police auxiliaries to assist the force in maintaining order. These were generally members of the Sturmabteilung (SA) with a smaller number of members of the AllgemeineSS, and others recruited from war veterans associations, who could be trusted to support the new and still not fully established regime. Similar Hilfspolizei units were created throughout the other German Lnder within a matter of days; they wore the uniforms of their parent organizations, if any, with a white Hilfspolizei armband. These auxiliaries were disbanded in August 1933 partly due to foreign protests that they contravened the terms of the Versailles Treaty, but also because Hitler was already becoming uneasy over his ability to control the SA, which provided the greater part of the Hilfspolizei.

Although short-lived, the Hilfspolizei had served their purpose in helping to ensure the survival of the Nazi government in the first shaky days of its existence, when it was still battling things out in the streets against strong Communist and socialist movements.

In January 1934, by now more confident, the regime began to unify the Landespolizei forces by transferring police powers to the national Reichs level; and from this point on in this text it is logical to capitalize the name of the service as Police. The post of Chief of the German Police in the Ministry of the Interior was created, and with Heinrich Himmlers appointment to this post in April 1934 the blurring of lines between the Police and the SS began. Himmler would ensure that the majority of senior and middle-level Police posts were filled by men who were also members of the SS and thus owed obedience to him. The new national Police apparatus that he controlled was divided into two major elements: the Ordnungspolizei (Order Police, Orpo) and the Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police, Sipo into which the Gestapo was absorbed).

When Germanys rearmament and the formation of the new Wehrmacht (armed forces) were openly declared in March 1935, many thousands of policemen were transferred to the Army, including those still serving who were perceived as lacking in enthusiasm for the Nazi regime. Senior ranks who remained in the Police and who were not already members of the SS were pressured into joining; membership became a prerequisite for a successful Police career. (It is interesting to note, however, that at the outbreak of war in September 1939 only some 15 per cent of the membership of the Gestapo were actually members of the SS.)

On the outbreak of war the manpower needs of the armed forces led to the conscription of many younger, fitter policemen; consequently, numbers of older men not considered fit for military service were taken into the Police as reservists for the duration and some of these were the very men who had been purged for perceived political unreliability between 1933 and 1935. Although the Nazification of the Police may have thus been somewhat diluted, it is unlikely that these men had much influence; their reputation for limited political loyalty would certainly have remained on their records, and they would continue to be regarded as suspect.

From 1942, dual Police and SS ranks were adopted by Police generals, who from then on would wear SS-pattern rank insignia, albeit in Police colours. Police personnel were also issued with pay books (Soldbcher) bearing the SS runes rather than the Police eagle on the cover.

As time passed, the Police, rather than providing the Army with manpower as originally envisaged, began to field its own rifle regiments and even light armoured units, to serve behind the military front lines in the occupied territories. Although many of these units were engaged in actions against heavily armed partisans, others were attached to SD Einsatzgruppen and used in sweeps through the civilian populations, rounding up Jews and other undesirables. It has now been well documented that the German Police although still maintaining tens of thousands of personnel on regular, traditional duties in Germany became deeply involved in some of the worse excesses of the Nazi regime.