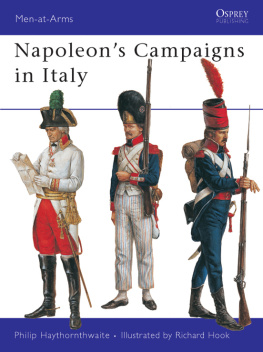

| Men-at-Arms 257 |  |

Napoleons Campaigns in Italy

Philip Haythornthwaite Illustrated by Richard Hook

Series editor Martin Windrow

CONTENTS

NAPOLEON IN ITALY

THE EARLY WARS

At the commencement of the French Revolutionary Wars, most of the important early campaigning occurred on the French frontiers with Germany and the Netherlands; but it was inevitable that conflict would also take place on the Franco-Italian frontier, due to the presence there of Frances enemiesmost notably the Austro-Hungarians, whose emperor was a driving force being the first coalition which sought to reverse the effects of the French Revolution.

Italy was divided into a large number of states, and had been relatively peaceful since the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had ended the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748. The Austrian Habsburg possessions in the north were considerable: Austria, in the person of the emperor, ruled Lombardy, including the duchies of Milan and Mantua; and although the grand-duchy of Tuscany was nominally independent, its ruler was the son of Emperor Leopold II (174792), who had himself possessed the state until he succeeded his brother Joseph II as emperor in 1790. The Spanish Bourbons ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Naples and Sicily) which extended north to the Papal States, ruled by the Vatican. The house of Savoy ruled Piedmont, Savoy, Nice and Sardinia; and the declining republics of Venice and Genoa were independent. Although the south was beset by feudalism and oppression, and despite the relatively liberal regime in the Austrian territories, most internal unrest was present in Piedmont, initially among the most affected by the spread of Jacobinism from France, and Milan.

With the hostile territories of the house of Savoy on their borders, the French were initially more concerned with securing their frontier than in exporting republicanism into Italy. Nevertheless, in 1792 Savoy and Nice were invaded by the French and seized with some ease, as the Piedmontese administration and forces were in no state to wage war, and the ruler, Victor Amadeus III, was but a pale shadow of his famous warrior father Charles Emmanuel III. Savoy was incorporated as a province of France, but no immediate further conquest was attempted. In 1793 France was beset by royalist risings in the south, Toulon was occupied by an Anglo-Spanish force, and until the autumn the situation of the French on the northern frontiers was parlous in the extreme.

Napoleon Bonaparte as he appeared at the beginning of the Italian campaigns, wearing the 1796-pattern coat of a gnral en chef. (Engraving by W. Greatbatch)

From January 1794 the French Army of Italy was commanded by General Pierre Dumerbion (173797); although the fighting against the Piedmontese was only sporadic, he acknowledged a great debt to his 25-year-old commander of artillery, Napoleon Bonaparte, who had recently been distinguished by his conduct at Toulon. In a remarkably mature and considered plan, young Bonaparte proposed a major French drive against Piedmont to compel Austria to transfer troops to bolster her north Italian possessions, thus weakening her resistance against the main French effort on the German front. Accordingly, Bonaparte was authorised to go to Genoa to reconnoitre for such operations; but following the purge of Robespierres supporters in the coup dtt of 27 July 1794 he was arrested on suspicion of treason, due partly to his friendship with Robespierres younger brother. Bonaparte was released when the reason for his Genoa trip was established, but his plans for an offensive in Italy were discounted by Lazare Carnot (17531823), who from August 1793 had been de facto French war minister and chief of general staff; he forbade offensive operations in Italy in order to concentrate resources on the Rhine. As operations against Piedmont tailed off, Dumerbion relinquished his command in November and retired the following May; and in early 1795, having an excess of generals, the war ministry placed Bonaparte on the unemployed list, his lack of seniority outweighing his precocious talent.

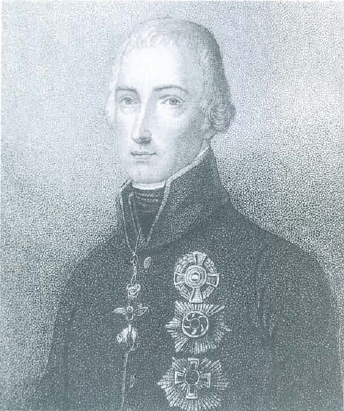

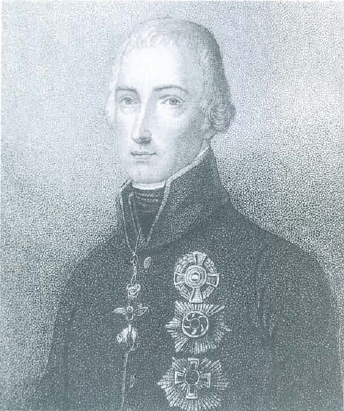

Emperor Francis II (17681835), who took the title of Francis I, Emperor of Austria, from August 1804. (Engraving by Blood after Shepperson)

General Barthelemy Schrer (17471804) took command in Italy, where he was opposed by an Austro-Piedmontese army ultimately led by the Austrian general Wallis. After a French renewal of operations, Wallis was surprised at Loano on 23 November 1795 and suffered a heavy defeat, the French success being owed more to General Andr Massena (17581817) than to Schrer. Due partly to the wretched condition of his army, Schrer made little attempt to exploit the victory, despite exhortations from Paris prompted by urgings from Bonaparte. His appeals for reinforcement unanswered, Schrer tendered his resignation, and on 2 March 1796 the Army of Italy received a new commander: General Napoleon Bonaparte.

Bonaparte and his army

Bonapartes rapid elevation from obscurity was a testimony to the changes in the military system occasioned by the French Revolution. The army of the Ancien Rgime had been virtually destroyed and rebuilt, and had lost a large proportion of its officersfrom emigration arising from their opposition to the republican government; and from purges which persecuted even loyal servants of the new republic (and encumbered commanding generals with political commissars who interfered to the great detriment of operations). Although the nucleus of the ex-royal army contributed to the successful defence of France in the early campaigns, a huge new army was created, initially from volunteers imbued with revolutionary fervour, and subsequently from a conscription which introduced the concept of a national war involving all citizens, instead of the small professional forces of the earlier 18th century. Such were the political constraints upon the military that even the term regiment was prohibited until September 1803, for its aristocratic connotation; it was replaced by demi-brigade (for the line infantry, demi-brigade de bataille, changed to demi-brigade de ligne in January 1796).

Occasioned originally by the need to field large numbers of volunteers or conscripts without time to train them fully, a new system of operation evolved. By uniting one ex-regular battalion with two new battalions in each demi-brigade, it was possible to combine the disciplined firepower and training for fighting in line of the regulars, with the charge in column, inspired initially by revolutionary fervour, which was the most practicable tactic of the untrained battalions. This ordre mixte (mixed deployment) was so successful in the early revolutionary wars that it was retained, and could be operated at all levels from battalion to division.

A second innovation was in light infantry tactics, previously restricted largely to irregular units operating on the flanks, front and rear of the army. With the new French forces, skirmishing and harassing the enemy with incessant musketry fired at will and in open order, instead of conventional volley-firing in close formation, reached an unprecedented level. By the mid-1790s the tactic had been perfected, combining

Next page