Campaign 83

Corunna 1809

Sir John Moores Fighting Retreat

Philip Haythornthwaite Illustrated by Christa Hook

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

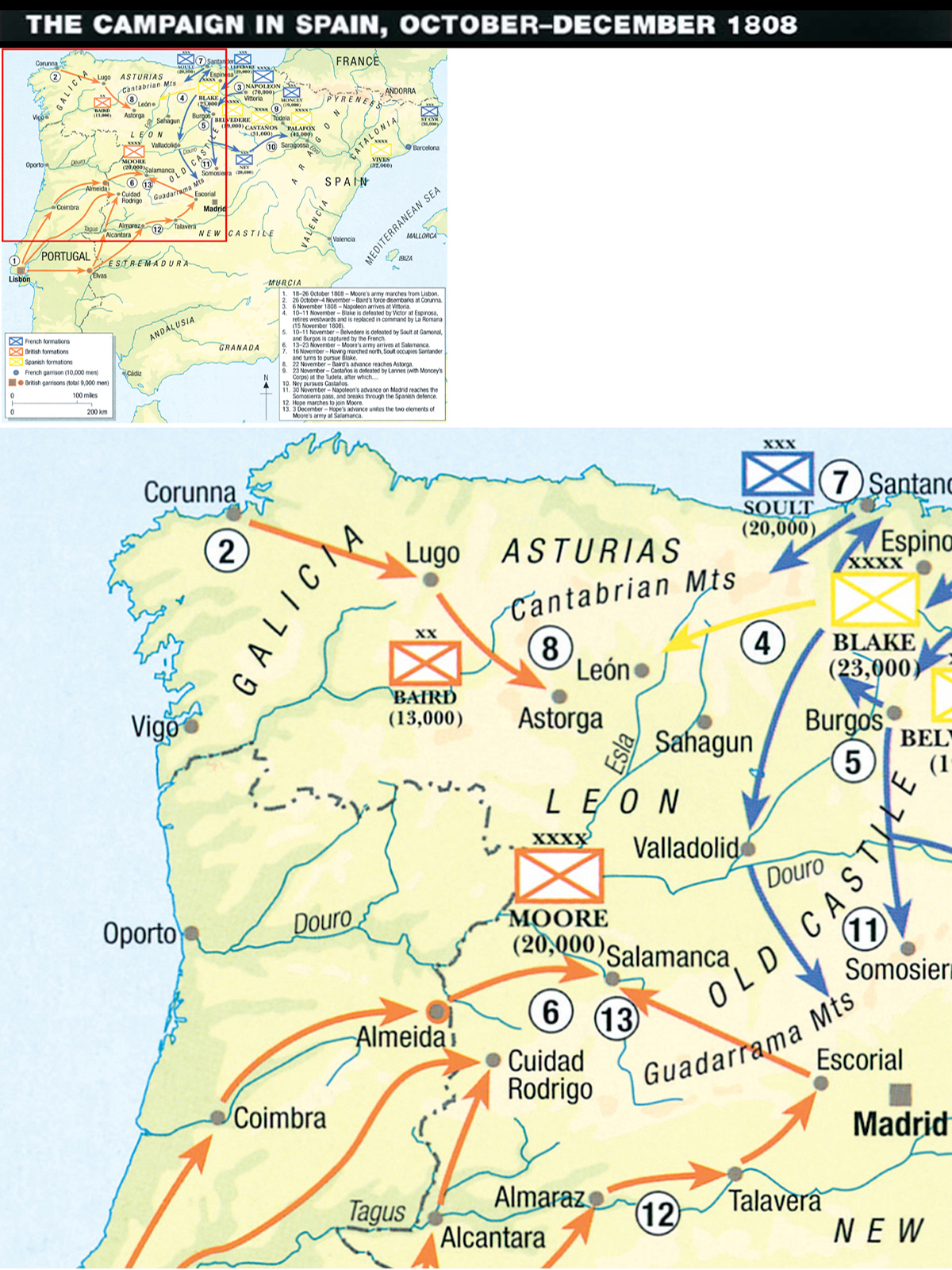

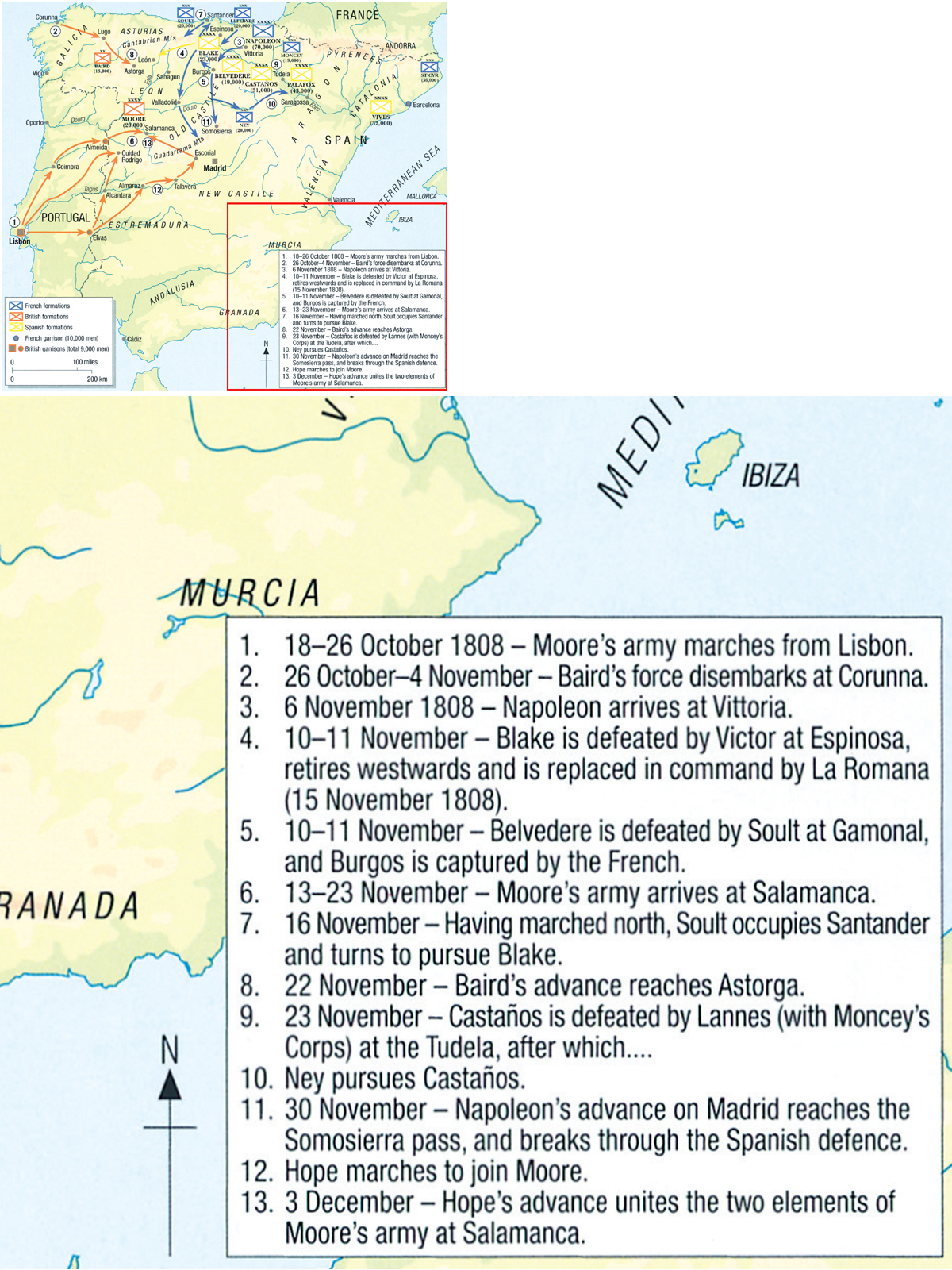

The French centre under Napoleon included the corps of Victor, Bessires (later Soult, which was sent west against Blake), Ney (sent east against Castanos), the Imperial Guard and reserve cavalry. The only Spanish forces shown are those concerned with the defence of the Ebro, and in Catalonia; others existed elsewhere.

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

T he Corunna campaign arose from the determination of the British government to continue its opposition to Napoleon by supporting the inhabitants of the Iberian peninsula in their attempt to resist French occupation. The first revolts in Spain convinced the British ministry that aid should be sent, for as the Foreign Secretary, George Canning, declared in the House of Commons on 15 June 1808, any opponent of France became an ally of Great Britain, and that involvement in the Peninsula was a matter of British national interest, for no interest can be so purely British as Spanish success.

Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, later 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (17691822), Secretary for War, a supporter of the British expedition to the Peninsula. (Engraving by T.W. Harland after Sir Thomas Lawrence)

Initially an expedition was sent to Portugal, where rebellion was threatening the tenuous hold on Lisbon maintained by the French army of General Andoche Junot. Command of the expedition was entrusted in the first instance to Sir Arthur Wellesley, a general with a successful record in India and a friend of the ministry, of which he had himself been a part. His initial force was to have a substantial reinforcement under Sir John Moore, who had recently returned from an abortive expedition to the Baltic. Wellesleys senior, Moore enjoyed a high reputation in the army and had a charismatic personality, but was regarded as a political opponent of the ministry; indeed, Moore has been described as the Whig general par excellence. It is perhaps worth remarking, however, that his employment by a Tory ministry demonstrates that political favouritism was not a dominant factor in the determination of such appointments. Nevertheless, while Moores abilities were probably too obvious to be ignored, his relationship with Lord Castlereagh, Secretary of State for War, was initially somewhat strained, and elements in the government seem to have doubted the wisdom of appointing him. Thus it was decided to place over his head (and thus over that of Wellesley) another general, Sir Hew Dalrymple, then commanding at Gibraltar. It is likely that Dalrymple was intended to be a temporary appointment only, until he might be replaced by the Earl of Chatham (brother of the late Prime Minister, William Pitt), or until Wellesley distinguished himself sufficiently to be given control of the enlarged expedition. Perhaps to prevent Moore from taking command should any mishap befall Dalrymple, Sir Harry Burrard was appointed as the latters official second in command.

Sir John Moore (17611809): an early portrait.

Such decisions must have been severe blows to both Moore and Wellesley, but the nature of both men led them to place public service before personal dignity, and due to their mutual respect the two could have worked well together as Wellington said he told Moore, you are the man, and I shall with great willingness act under you.

In the event that never occurred. Wellesleys expedition landed and defeated Junots French army at Rolica (17 August 1808) and Vimeiro (21 August), although the arrival of the over-cautious Burrard prevented exploitation of the success. Upon Dalrymples arrival in chief command, Junot was able to negotiate the Convention of Cintra, by which French forces were evacuated by sea from Portugal with baggage and loot intact instead of being compelled to surrender. Although it did secure for Britain a Portuguese base without further fighting, the convention was greeted with outrage in Britain. The three British generals were recalled for an inquiry, from which only Wellesley emerged with his reputation unscathed he had acquiesced to the convention only with the greatest reluctance. With the removal of these three, however, Moore was left in command of the British forces in Portugal, from 6 October 1808.

Sir John Moore in the uniform of a lieutenant-general. (Engraving by Charles Turner after Sir Thomas Lawrence)

By this time, Napoleons plans for the peninsula were going awry. Although his brother Joseph had been installed as king of Spain in place of the legitimate royal family, he was accepted by only a small minority of the Spanish population, insurrection was widespread, and several Spanish armies were in the field to oppose him. On 19 July 1808 the French cause had suffered a severe blow with the surrender of General Pierre Duponts army to the Spanish forces of Xavier Castaos at Baylen, and the loss of Portugal compounded the situation. Napoleons exasperation is evident from his correspondence with Joseph, who following Baylen had abandoned his capital, Madrid: Dupont has dishonoured our flag. What incapacity, what cowardice! All that goes on in Spain is deplorable. The army seems to be commanded, not by generals or soldiers, but by postmasters.

Napoleons solution, as might have been expected, was not only to increase dramatically the number of French troops in Spain, but to take command in person. After ensuring that there would be no immediate distractions from central Europe arising from his absence confirming his alliance with Russia in a conference at Erfurt and making veiled threats against Austria Napoleon was free to transfer veteran divisions to Spain, and on 3 November arrived at Bayonne in person.

Anderson p.55

Stanhope, Earl, Notes on Conversations with the Duke of Wellington, London 1888, p.244

Napoleon, Vol.I pp.343, 346

OPPOSING COMMANDERS

THE FRENCH

A lthough he did not command in person in any of the actions against Moore, Napoleon Bonapartes presence in Spain can hardly be over-emphasised. In the winter of 1808 he was probably near the peak of his military powers, his most recent campaigns having resulted in the rapid and overwhelming defeat of Prussia in 1806, and the succeeding victories over Russia at Eylau and Friedland. The importance of Napoleons presence in the theatre of war extended beyond his own battlefield talents. He was able to supervise the armys administration and remedy many of its faults, and more significantly to impose an overall strategy with a clarity of direction which had been lacking, and which could not have been achieved from a greater distance. In the later Peninsular campaigns, French operations suffered from the virtual independence of the various armies, and from the mutual dislikes and jealousies among the commanders, which seriously impaired collaboration. Without Napoleons presence in 1808 it is possible these factors might have occurred as they did in succeeding years. In Napoleons next campaign, the war against Austria in 1809, he was to suffer the first serious check to his military career, which might be taken as a sign that his abilities had begun to wane; but although his time in Spain was relatively short, it resulted in an immense improvement in French fortunes.