First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Carole Divall, 2012

ISBN 978-1-84884-842-9

eISBN 978-1-78337-866-1

The right of Carole Divall to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire.

Printed and bound in England by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and

Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Dedication

To John and Mary, good friends and fellow travellers on the retreat from Burgos

List of Maps

List of Plates

Preface

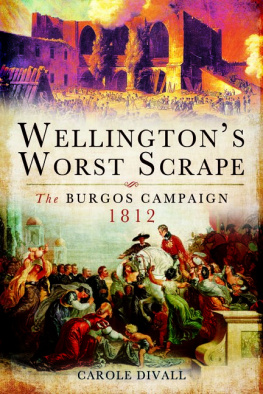

On 12 August an Anglo-Portuguese army under the command of Arthur Wellesley, Lord Wellington, marched in triumph through the streets of Madrid. The conquerors of the border fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz, and the victors of Salamanca, had brought the war against the French to the very heart of Spain. Three months later, that same army under that same commander were once more on the Portuguese border, where their campaign had started eleven months before. They had not marched back in triumph. Instead they had slunk away from Salamanca and dragged themselves back through torrential rain and ankle-deep mud. Between the August triumph and what in November looked like defeat lay the fortress of Burgos, the only fortress that successfully resisted Wellingtons attempt to take it, and the site of his worst scrape.

Both the failed siege and the retreat that followed, as well as the French campaign which chased the allied army back to Portugal, are stories of human endeavour which embrace all that is best and all that is worst in human nature. Deeds of great courage and humanity marched in tandem with cruelty, despair and all the excesses of indiscipline. For the nations involved Britain, France, Spain and Portugal there was much to admire and much to deplore.

There are many histories of these events, from the monumental works of Napier, Oman and Fortescue to modern reinterpretations, often with a specific national focus, which seek to reinterpret what happened at Burgos and afterwards. Military historians inevitably focus on strategy and tactics, on the objectives and achievements of a campaign and the mistakes made. They create what might be termed the big military picture. However, there are other stories to be told: the stories of the thousands of men who marched and fought and died in the autumn of 1812.

Interestingly, the first account of the retreat, which was published in 1814, was written by an assistant surgeon, George Frederick Burroughs, whose intention seems to have been not just to relate what happened, but also what it felt like to be part of the events he was describing. What I have tried to create, in this study of Wellingtons worst scrape, as he himself termed it, is a similar focus on the experiences and perceptions of those involved, from the men in command to those in the ranks and even those who trailed behind the armies.

The Napoleonic Wars are notable for the wealth of written material they generated, either in the form of contemporaneous accounts in letters and journals or in later productions such as memoirs. Although Wellington himself refused to write a memoir, he wrote copious letters, official dispatches which nevertheless give clear glimpses both of his intentions and objectives and his state of mind. These letters and memoranda provide an invaluable structure for a study of Burgos and the retreat. They can then be amplified by the thoughts, feelings and opinions of others involved in the struggle for Spain. Among the different voices which inform this work and provide a commentary on the actual events are senior and junior officers, British and French, NCOs and soldiers from the ranks, non-combatants like surgeons and commissaries, and the occasional civilian who found himself caught up in an alien environment. Between them they create a multi-faceted view of their world, of what happened in it, and of the major players involved. They praise and they criticize; they are puzzled by things that appear to make no sense; or perhaps they just struggle to survive. Above all, though, they live on through their words.

Obviously, from a strictly historical perspective, letters and journals may be regarded as having more validity and authority than memoirs, which were often composed many years later. This is particularly true of those memoirs written after Napier produced his history of the Peninsular War, a brilliant literary effort which had an inevitable influence on those who subsequently wrote their own accounts. But such accounts should not be totally disregarded. What a man remembers, or is stimulated to remember by the writing of others, may reveal the relative significance of the events he experienced. Nor should every letter and journal be regarded as presenting an unvarnished version of the truth. Situations may easily be misunderstood. Opinions are often coloured by prejudice. What a man experiences may be only a small part of the whole. Consequently, it is the sum of the many parts, contemporaneous and retrospective, which enable us to recognize through a glass darkly the reality of experiences from two centuries ago.

Acknowledgements

Once again I have every reason to be grateful to the staff of the National Archives at Kew and the National Army Museum in Chelsea for their help and expertise. Particular thanks are due to Richard Dabb at the NAM for his assistance in accessing images for this book.

As ever there have been many friends and associates who have helped me locate particular information, or have made suggestions about particular material that might prove useful. Such suggestions have proved invaluable as I have attempted to recreate the experience of Burgos and the retreat. Michael Crumplin FRCS has been particularly supportive in making available a wealth of medical information. He also enabled me to access the reports of Wellingtons surgeon general, James McGrigor, which shed a fascinating light on the medical conditions of the British army in the Peninsula. McGrigors findings also help to explain why there were so many casualties; wounded men who should have recovered but failed to do so, and hundreds who died of natural causes. (See .) I am grateful to the Aberdeen Medico-Chirurgical Society for allowing me to make use of this unpublished material.