Campaign 48

Salamanca 1812

Wellington crushes Marmont

Ian Fletcher Illustrated by Bill Younghusband

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

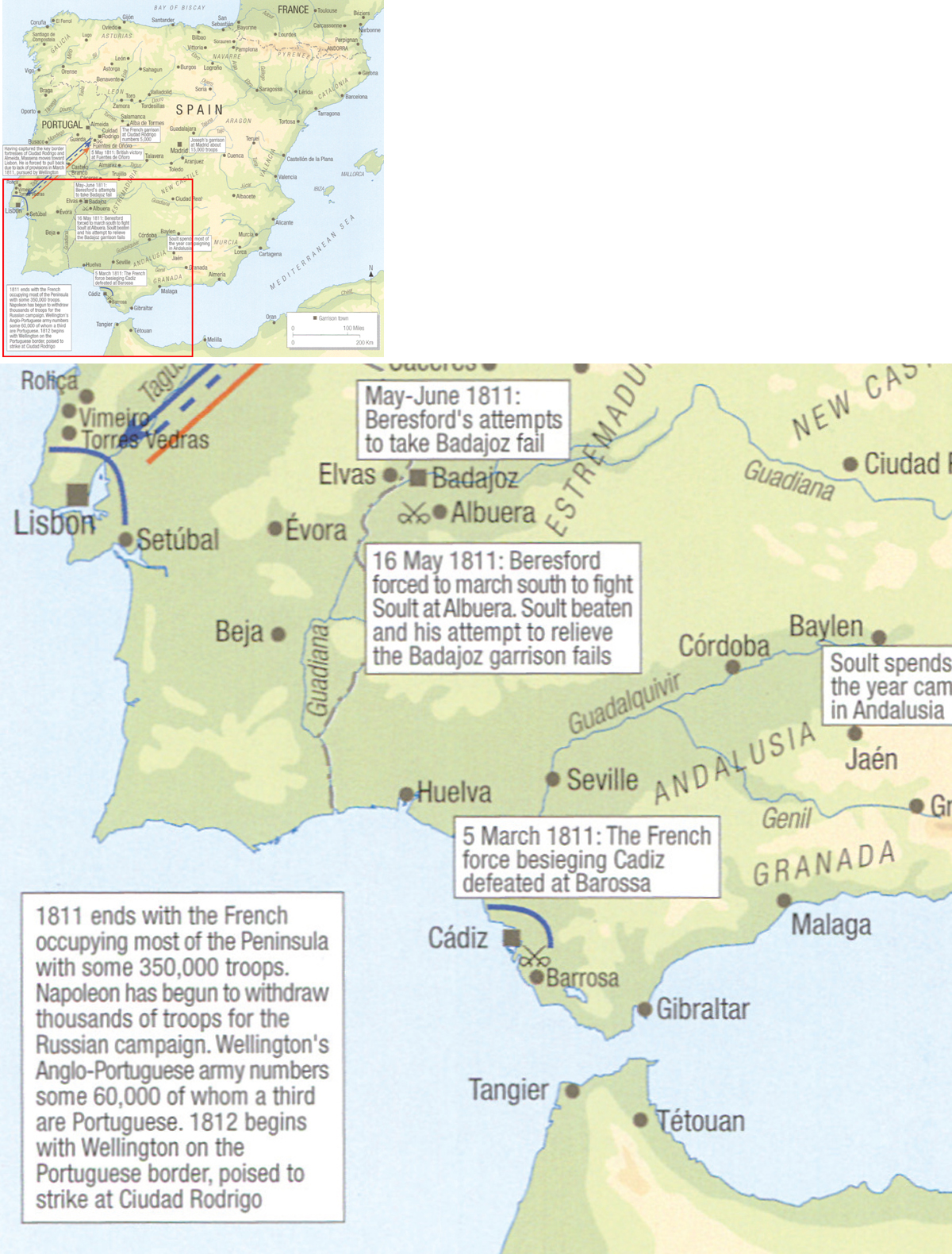

ACTIONS IN THE PENINSULA 1811

The Battle of Corunna, 16 January 1809. Sir John Moore is carried from the field after being mortally wounded by an enemy cannonball. Moores efforts during the harrowing Corunna campaign ensured that the British army was able to re-embark and return to England in relative safety, even though it cost him his life. (After a print by Durpray)

INTRODUCTION

O n 22 July 1808, HMS Crocodile nudged its way into the port of Corunna in northern Spain, with Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur Wellesley on board. Wellesley had sailed to Spain as commander of a 14,000-strong British force with the intention of supporting the people of both Portugal and Spain who had risen up against the invading French armies. Unfortunately, Wellesley was told in no uncertain terms by the local Spanish Junta that his presence, and that of his army, was not welcome, and he was advised to continue his journey along the coast of Portugal and seek help there. Wellesley departed Corunna on 24 July. Four years later almost to the day Sir Arthur, by then Lord Wellington, achieved one of his greatest successes on the field of battle when he defeated the French Army of Portugal under Marshal Marmont at the battle of Salamanca.

The road to Salamanca involved four years of hard slog for Wellington, who had to contend not only with numerically superior enemy forces, but with an anxious British government, worried lest its only army perished on the dusty Iberian plains. Added to this was the so-called croaking, the whispering campaign conducted by some of Wellingtons own officers who saw little prospect of success, and who advocated evacuating the Peninsula as soon as possible. This campaign reached its height during the spring and summer of 1810, although by the spring of 1811, when Massenas starving French army had been forced from Portugal following its disastrous sojourn in front of the impenetrable Lines of Torres Vedras, even the croakers could see some light at the end of the tunnel.

An incident during the battle of Vimeiro, 21 August 1808. Although it was fought four days after the battle of Rolia, this was Wellesleys first important victory in the Peninsula and one which brought his name to the fore throughout Europe.

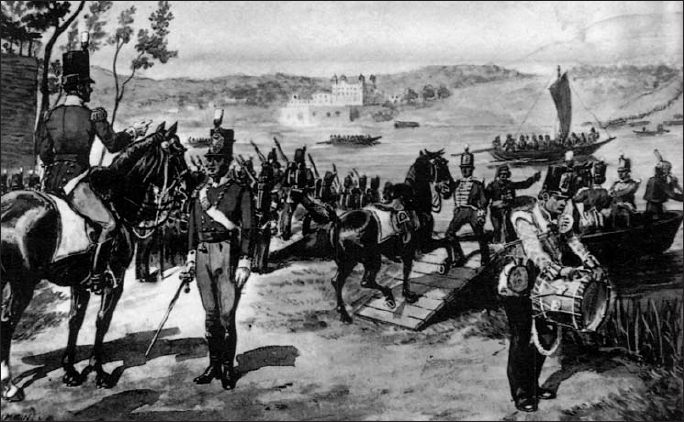

The crossing of the Douro, 12 May 1809. Following his return to the Peninsula, after having been acquitted of all charges arising from the Convention of Cintra, Wellesley drove Soult from Portugal in a daring operation which involved his men crossing the Douro beneath the very noses of the French, suffering very few casualties in the process. (After a painting by Simkin)

The British armys campaign in the Peninsula began in August 1808 with a landing at the mouth of the Mondego River at Figueras. On 16 August the army fought its first action, near an old mill at Brillos, and suffered its first casualty of the war, Lt. Bunbury, of the 95th Rifles. The following day Wellesleys army fought and won its first battle, at Rolia, although by later standards this was really nothing more than a large skirmish. On 21 August Wellesley defeated Delaborde at Vimeiro, his first major victory, and a battle which gave a clear indication how victory in the Peninsula was to be achieved. The dense French columns crumbled before the superior firepower of the British line, aided and abetted by Wellesleys skilful choice of position and by the efficient use of his limited artillery. Sadly, and perhaps more ominous, was the behaviour of the British cavalry, on this occasion the 20th Light Dragoons, who performed the first of a series of ill-managed charges, something which was to continue right up until Waterloo some seven years later. But if the victory at Vimeiro ushered in the beginning of a long series of triumphs of the British line, it also marked one of the most controversial incidents of the Peninsular War, the notorious Convention of Cintra.

The convention was signed following an armistice, agreed between Wellesley and Gen. Kellerman, representing Junots French army. Prior to the signing of the convention, Wellesley had been superseded by two senior generals, Sir Hew Dalrymple and Sir Harry Burrard, who had arrived from England, while a third, Sir John Moore, was also on his way to Portugal. Under the terms of the convention, the defeated French army was allowed to sail back to France in British ships with all of its accumulated plunder as well as its arms. Naturally, this outraged the people in Britain and Wellesley, Dalrymple and Burrard were recalled to England to face a Court of Inquiry.

The 48th Regiment in action during the battle of Talavera, 27-28 July 1809. The battle was Wellesleys first in Spain following his return to the Peninsula in April 1809. (After a painting by Simkin)

Meanwhile, the British army was driven from Spain by Marshal Soult who, on 16 January 1809, had fought the battle of Corunna against a British army under Sir John Moore. The resulting British victory allowed the army to embark in relative safety, although it cost Moore his life. The retreat to Corunna was also one of the more harrowing episodes of the war, as the discipline of many British units vanished amid the snows of the bleak Galician mountains. The episode was to be repeated in November 1812 during the retreat from Burgos, which was said by many to have been the more terrible of the two.

Wellesley was acquitted of his part in the Convention of Cintra and he returned to Portugal on 22 April 1809, when his ship, HMS Surveillante, sailed into Lisbon. Within just three weeks he had formulated his strategy for ejecting the French from Portugal and on 12 May, in one of the most daring operations of the war, his men crossed the River Douro and drove Soults men from the city of Oporto. By the end of the month Portugal was clear of the so-called Army of Portugal. From Oporto, Wellesley turned south to link up with the Spaniards under the ageing Gen. Cuesta, although the alliance between the two men was not one of the most productive. The Spaniards failed to make good their promises of supplies or, more importantly, transport. Moreover, Cuesta was loathe to take orders from Wellesley, whom, somewhat ironically, he regarded as an English heretic. The two men, however, did manage a degree of co-operation and by the summer of 1809 had concentrated their forces at Talavera. Here, on 27-28 July, with little or no help from his Spanish allies, Wellesley achieved one of his most hard-fought victories beneath the blazing Spanish sun. The two-day battle cost him some 5,000 casualties against 7,500 French, but it did earn him the title of Lord Wellington, Marquis of Talavera, a name first used by him when, on 27 September 1809, he signed himself Wellington.