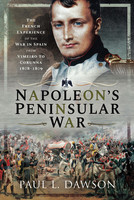

Charging Against Wellington

Napoleons Cavalry in the Peninsula 18071814

This edition published in 2011 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Limited, 47 Church Street,

Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.frontline-books.com

email

Robert Burnham, 2011

The right of Robert Burnham to be identified

as Author of this Work

has been asserted by them in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 9781848325913

ePub ISBN:9781844684366

PRC ISBN: 9781844684373

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any

means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without

the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised

act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil

claims for damages.

A CIP data record for this title is available from the British Library.

For more information on our books, please visit

or write to us at the above address.

Typeset by Palindrome

Printed in the UK by CPI Antony Rowe

Contents

Illustrations

Plates may be found between pages 156 and 157

List of Tables

Foreword

Procella equestris a hurricane of cavalry is how French General Count Maximilan Sebastien Foy described Napoleons imperial squadrons in his uncompleted 1827 Histoire de la guerre de la pninsule sous Napolon. In capable hands the Napoleonic mounted storm could be swift, sweeping, spectacular. At times it was devastating. When opportunity offered, the emperors cavalry, in small numbers or great, demonstrated decisive power at battles like Medina de Rio Seco in July 1808 and Medellin in March 1809. At Maria in June 1809 a single Polish squadron unhinged the Spanish defence and at Ocaa, five months later, the cavalry under Sebastiani played a key role in perhaps the largest Napoleonic battlefield capture to date Marshal Soult reported 26,000 Spanish prisoners.

The Anglo-Portuguese army, too, shared discomfiture at the hands of imperial troopers, as at the Coa River in 1810 and at Fuentes de Ooro and Albuera in 1811. Small wonder that French cavalry in numbers worried Arthur Wellesley, commander of the British expeditionary force. Charging Against Wellington traces how Frances hurricane of horsemen was organised and led through the harsh war fought across the Iberian Peninsula and southern France from 1807 to 1814.

Frances cavalry were also called upon to assist in a relentless and widespread little war, el guerrilla, which often required regiments to be dispersed in isolated, self-reliant detachments to pacify or garrison a locality, act as escorts, or conduct mobile operations against partisans (guerrillas). When we marched from one province to another, wrote Sublieutenant Albert Jean Michel de Rocca, a Swiss in the 2nd Hussars, in his 1814 memoir of Iberian service,

the partisans immediately reorganised the country we had abandoned in the name of Ferdinand VII, as if we were never to go back, and punished very severely every one who had shewn any kind of zeal for the French. Thus the terror of our arms gave us no influence around us. As the enemy was spread over the whole country, the different points that the French occupied were all more or less threatened; their victorious troops, dispersed in order to maintain their conquests, found themselves, from Irun to Cadiz, in a state of continual blockade; and they were not in reality masters of more than the ground they actually trod upon.

Portuguese and Spanish resistance to Frances sustained effort to occupy and pacify the Peninsula required frequent redistribution of the Emperors cavalry and changes of command structure. The very geographic breadth and duration of the Peninsular War, as well as its remoteness from imperial headquarters, however, challenged not only the capacity of Napoleon and his staff to track and record his armys evolving position and field-organisation, but generations of subsequent historians to elucidate it accurately.

Robert Burnhams study of French imperial cavalry untangles the tale clearly. Divided into three sections, Charging Against Wellington guides the reader through the arms organisational commitment in the Peninsula, supported by over 250 tables and 80 biographical sketches of the generals who commanded it.

Part One, with 57 organisational tables, charts the regimental composition and leadership of Frances cavalry brigades and divisions, as well as their assignments to divisional, army corps, and army commands throughout the war. Its four chapters traverse the conflicts arc, from creeping invasion, beginning in late October 1807, to an attempted conquest which, by 1810, was supported by 40,000 troopers, to the difficulties of occupation and pacification, followed by the long retreatthat ended in southern France in April 1814. Meeting the shifting needs of each of these phases, and the unique military requirements of each region of the Iberian Peninsula, required frequent changes in command structures and regimental assignments.

Part Two analyses, as a group, the generals who commanded cavalry formations during the six and a half years of the Peninsular War, and includes compact biographies of each of them. A rapid battlefield-glance (coup-dil), impulsive determination, combined with youthful vigour, good eyesight, ringing voice, athletic dexterity, and a centaurs agility, were all necessities for an outstanding cavalry general, observed General Foy in his History, but above all: a prodigal supply of bravery. Unfortunately, bravery (and disease) exacted a heavy toll: only 57 per cent of the cavalry generals survived their service in the Peninsula alive, unwounded, and uncaptured. Moreover, a war largely waged far from theimmediate gaze of the emperor lacked opportunities for noticed glory and ensuing advancement. Nevertheless, while some cavalry generals exposed their leadership deficiencies (nine were relieved for cause), others, such as Delort, Milhaud, Montbrun, Tour-Maubourg and Watier, proved themselves to be highly capable.

Part Three of Charging Against Wellington presents a tabular outline of key data including which squadrons of a regiment were present and when, major commands to which assigned, battles in which they fought for each of the 54 French, 2 foreign auxiliary, and 11 allied cavalry regiments serving the Emperor in the Peninsula, as well as for some 25 provisional cavalry regiments formed for service there. By 1812 half of all French cavalry regiments had sent one or more squadrons to Spain or Portugal. Yet with over 500,000 square kilometres of Iberian Peninsula to secure against an hostile population supported by the British army and Royal Navy, and competing wars in eastern and central Europe, there simply were never enough horsemen.

Charging Against Wellington neatly catalogues and describes the service of the Emperors cavalry so that its organisation can be explored and traced from almost any level, and its generals placed in the context of their commands and accomplishments. Synthesising as it does a wealth of data, Robert Burnhams study will reward both the casual enthusiast of the Peninsular War and the researcher or scholar seeking to follow the threads or patterns of organisation and leadership of Napoleons mounted arm during that long and costly campaign.

Howie Muir

Next page