Matsumoto Castle

Osaka Castle

Kumamoto Castle

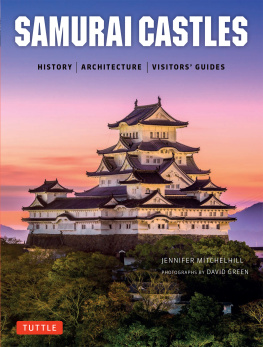

SAMURAI CASTLES

HISTORY | ARCHITECTURE | VISITORS GUIDES

JENNIFER MITCHELHILL

PHOTOS BY DAVID GREEN

Preface

Just before the largest clash of samurai in Japanese history, at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Chiyo, the wife of samurai Yamauchi Katsutoyo, wrote her husband a letter, concealing it in the chin strap of a messengers hat.

The Battle of Sekigahara, fought between the two major powers, the Toyotomi and the Tokugawa, was to decide the fate of Japan for the next 268 years. The side on which a samurai chose to fight would determine his fate and that of his family for generations to come. The stakes were high and loyalties ran deep. To fight on the losing side meant loss of territory, loss of ones master and the life of a wandering, masterless samurai called ronin. Victory could have gone either way. It was finally determined by the betrayal of a Toyotomi loyalist general who defected to the Tokugawa side in the midst of the battle.

Chiyo had received word of the potential betrayal. Her husband, Yamauchi, had served under the great sixteenth-century leader Oda Nobunaga and his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Her letter relayed vital information about Toyotomi forces and suggested her husband switch allegiance. Fortuitously, Katsutoyo took her advice and fought on the winning Tokugawa side. As a reward, he was made first lord of the province of Tosa on the island of Shikoku. With Chiyo, he constructed Kochi Castle, beginning the Yamauchi dynasty where 16 consecutive generations ruled Tosa over the following 268 years. In recognition of Chiyos efforts, today a bronze statue of Katsutoyos wise wife watches over the approach to the main citadel.

Japanese castles are rich in stories of intrigue, sacrifice and betrayal. They stand as majestic monuments to the samurai who once ruled Japan.

Some 160,000 samurai fought in the battle of Sekigahara on October 21, 1600 to determine the supreme ruler of Japan. The Eastern Army led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the Western Army led by Ishidi Mitsunari, each comprised allied daimyo (feudal lords) from provinces all over Japan. The banners painted on this Japanese screen show the family crest of the 40 or so daimyos armies who took part in the battle. After a day of fighting and the loss of 40,000 lives, Tokugawa Ieyasu declared victory. Thus began the 268-year rule of Japan by the Tokugawa shogunate. (Late Edo era, 19th century. Collection of the City of Gifu Museum of History)

Introducing Japans Samurai Castles

Japanese castles as we know them today were predominantly built in the late sixteenth century. This was a time when warriors introduced themselves before engaging in hand-to-hand combat, when honor could be restored by slicing open ones abdomen, and when great attention was paid to the rituals of the tea ceremony, poetry writing and dying.

Regional warlords had been fighting over territory from about 1470. By the mid-sixteenth century, a few were anxious to unify the country and secure absolute power. The central characters were larger than life and stories of their courage, skill and sheer audacity have entertained generations for over 400 years. Among them were Oda Nobunaga (153482), the ruthless youth who used courage and exceptional military skill to subdue enemies with armies five times the size of his; Toyotomi Hideyoshi (153698), the poor peasant boy who rose to rule the country; and Tokugawa Ieyasu (15421616), the shrewd warlord who worked quietly in the background, waiting patiently before taking control of the country.

One of the most imposing legacies of this period is the Japanese castle. During the scramble to unify the country, daimyo (lords of a domain) built castles to protect their territory and act as a base from which to rule their domain. Representative of a daimyos power and wealth, these grand fortresses were cunningly planned to confuse the enemy on their approach to the main keep. Should an attacking army successfully cross a moat and scale the outer stonewalls, numerous shooting holes and trapdoors allowed the besieged samurai to bring their weapons to bear on those below. Constructed predominantly of wood, the vulnerable main buildings were adorned with symbols to ward off the enemy, fire and the elements.

Of the hundreds of castles built in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, only a handful have survived in their original condition. Hundreds were ordered to be demolished when the country was unified by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1582. Hundreds more were destroyed by the Tokugawa shogunate (military government) in 1615. The majority of the remaining 170 or so castles fell victim to Imperial orders to destroy any trace of Japans feudal past after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Allied bombing during World War II razed seven of the 19 remaining main castle towers (tenshu), leaving countless subsidiary towers, stonewalls, gates and moats.

The 100 or so castle sites that can be visited today offer a fascinating glimpse into Japans past. This book explains the historical background to Japanese castles, who built them and why. It describes their construction and their form. Finally, it presents 24 of the best surviving castles.

Japanese castles were as much a symbol of power as a fortification. The multistoried main tower (tenshu), with its graceful arrangement of sweeping roofs, dominated the surrounding landscape. Usually sited on raised ground, the tower served both as a lookout and as a reminder of the lords authority. (Hiroshima Castle)

A History of the Japanese Castle

The Siege of Osaka Castle. Although effectively becoming the most powerful daimyo after his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Tokugawa hegemony was not assured until Toyotomi Hideyoshis heir, Hideyori, was disposed of. In the winter of 1614, then again in the summer of 1615, Tokugawa forces besieged Osaka Castle. This screen shows the Summer Battle of Osaka Castle in 1615. Over 5,000 samurai and 21 generals are depicted. One of the generals, Kuroda Nagamasa, took painters with him to the battle site to obtain an authentic rendition of events.

Long before the Japanese castle as we know it today took shape, simple fortifications were used as a defense against invading forces and internal warring factions. Their use is first recorded in the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan), written in the eighth century. The Nihon Shoki details the fight between two powerful court families, the Soga and the Mononobe, in AD 580. Their disagreement concerned Buddhism, introduced via Korea in 552. The Soga welcomed the new religion while the Mononobe saw it as a threat to their political influence.