First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Chris Peers 2013

HARDBACK ISBN: 978 1 84884 790 3

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47383 127 8

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47383 011 0

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47383 069 1

The right of Chris Peers to be identified as the Author of this Work has

been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Driffield, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon,

CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History,

History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social

History, Transport, True Crime, and Claymore Press, Frontline Books,

Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing

and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

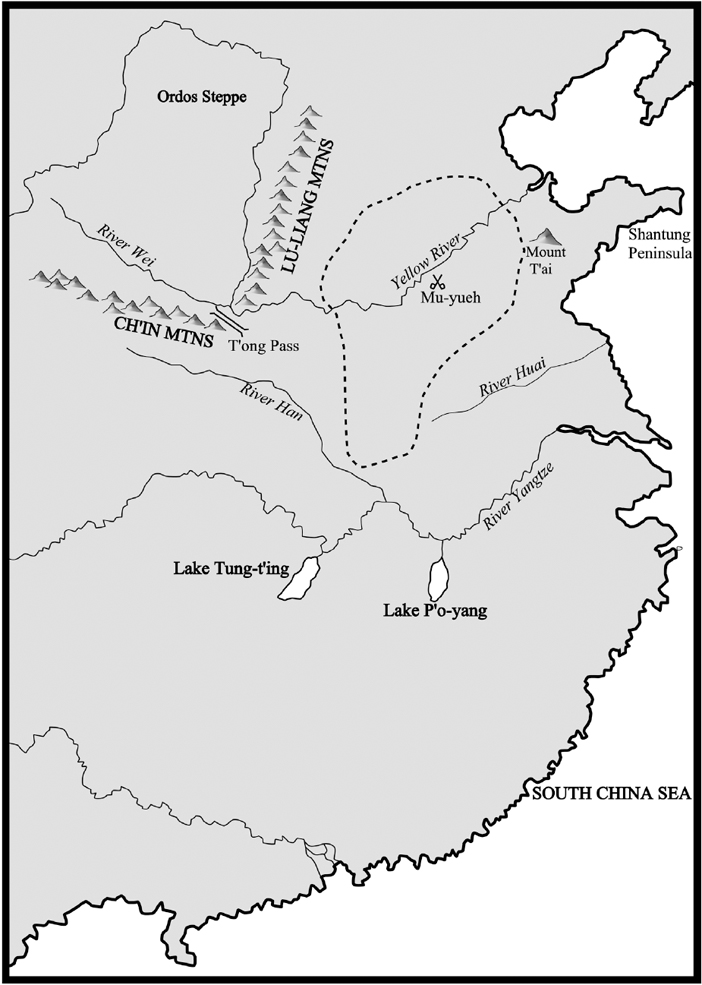

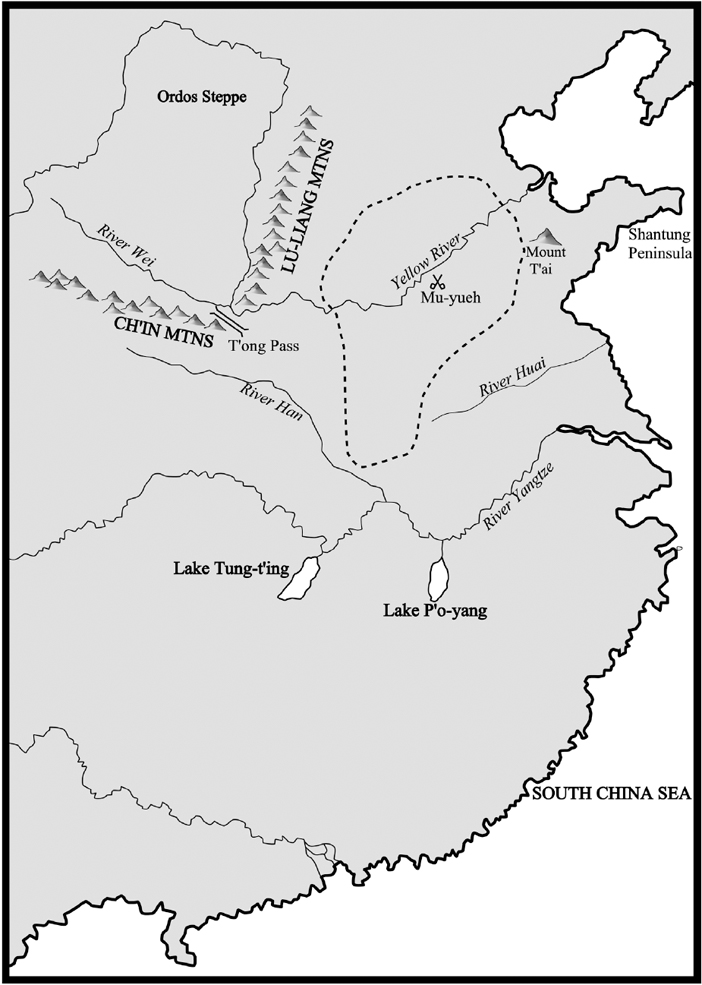

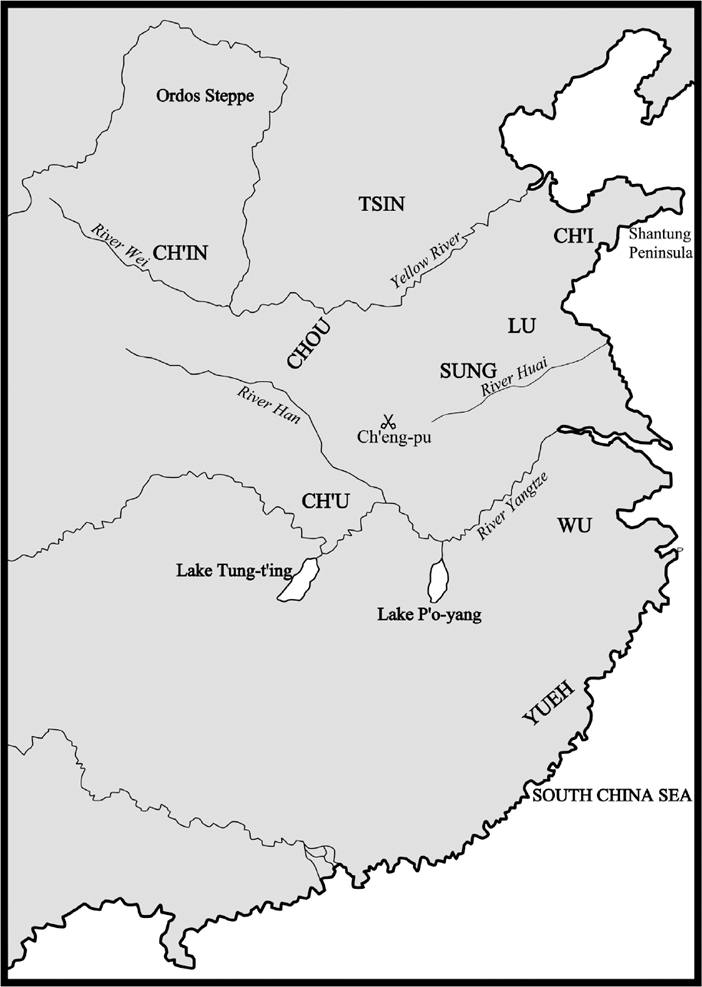

The main geographical features of ancient China. The dotted line denotes the approximate extent of the Shang kingdom before its overthrow at the hands of the Chou in the eleventh century BC.

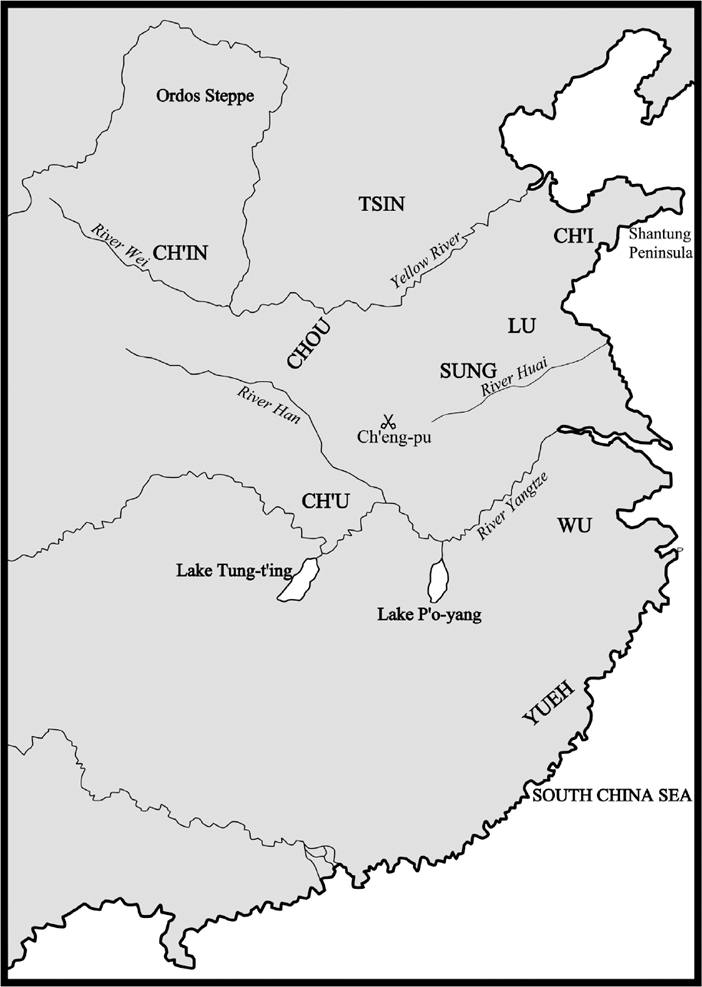

China in the Springs and Autumns period, showing the locations of the main contenders in the wars of the seventh century BC.

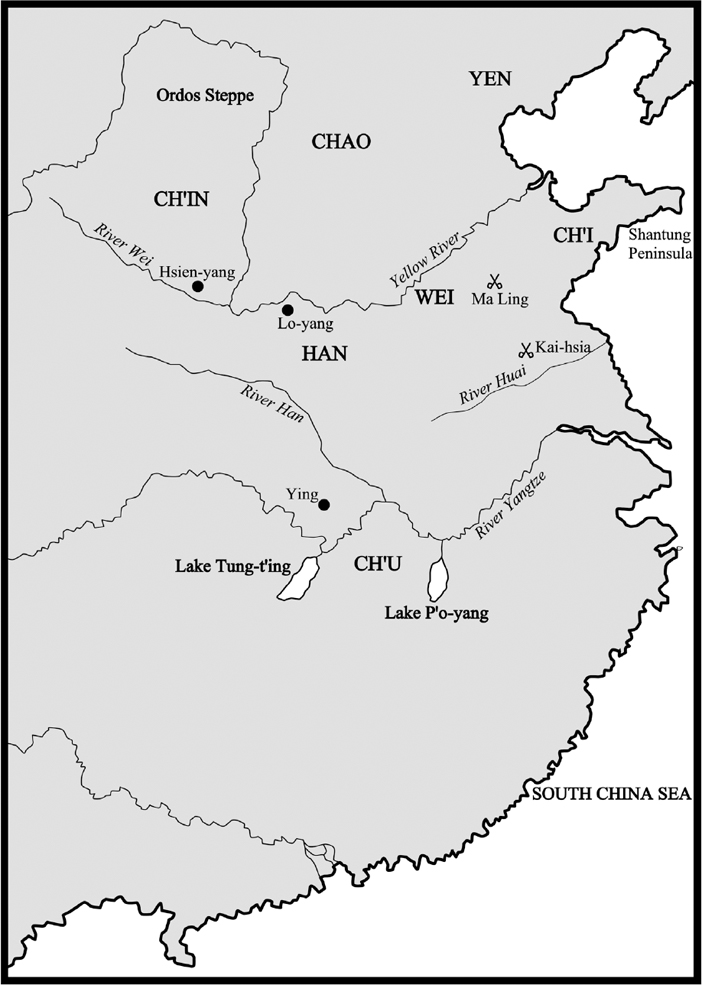

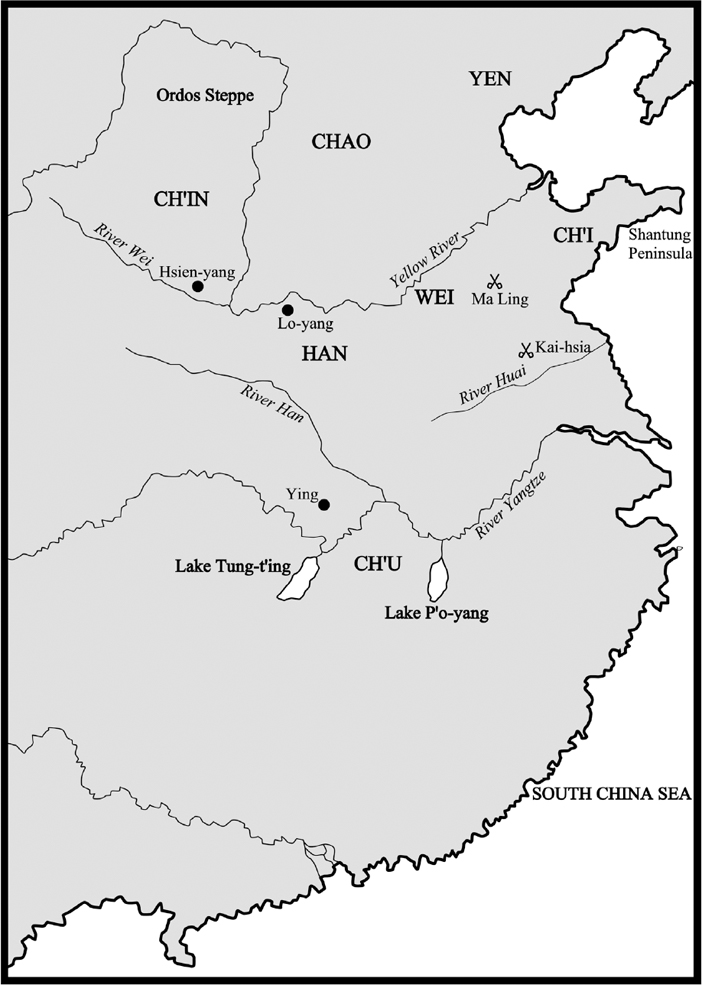

The Warring States, c. 300 BC.

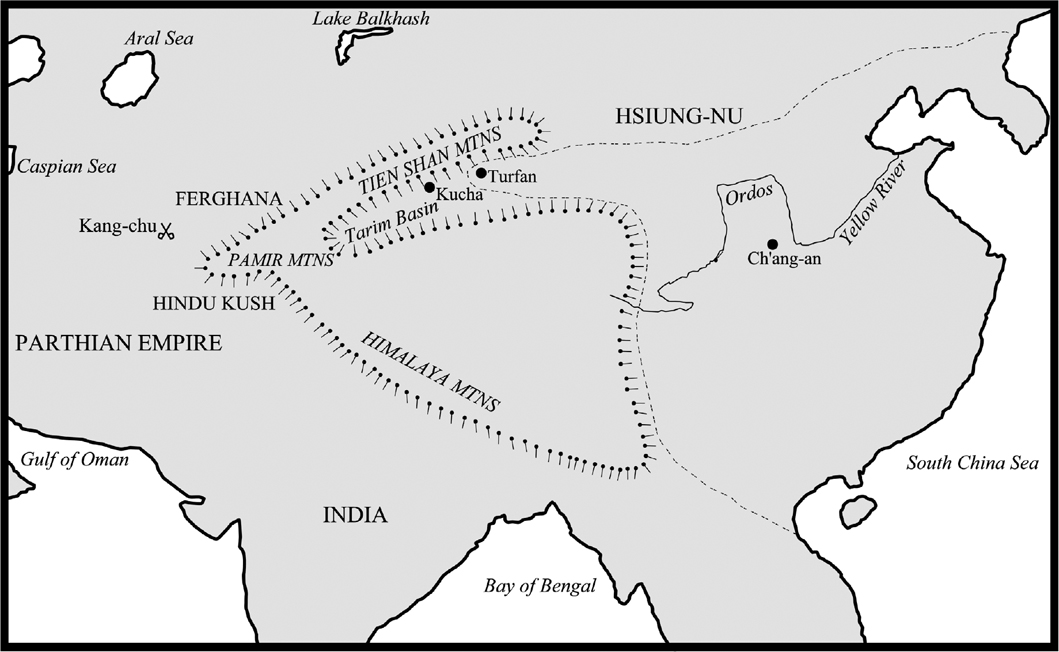

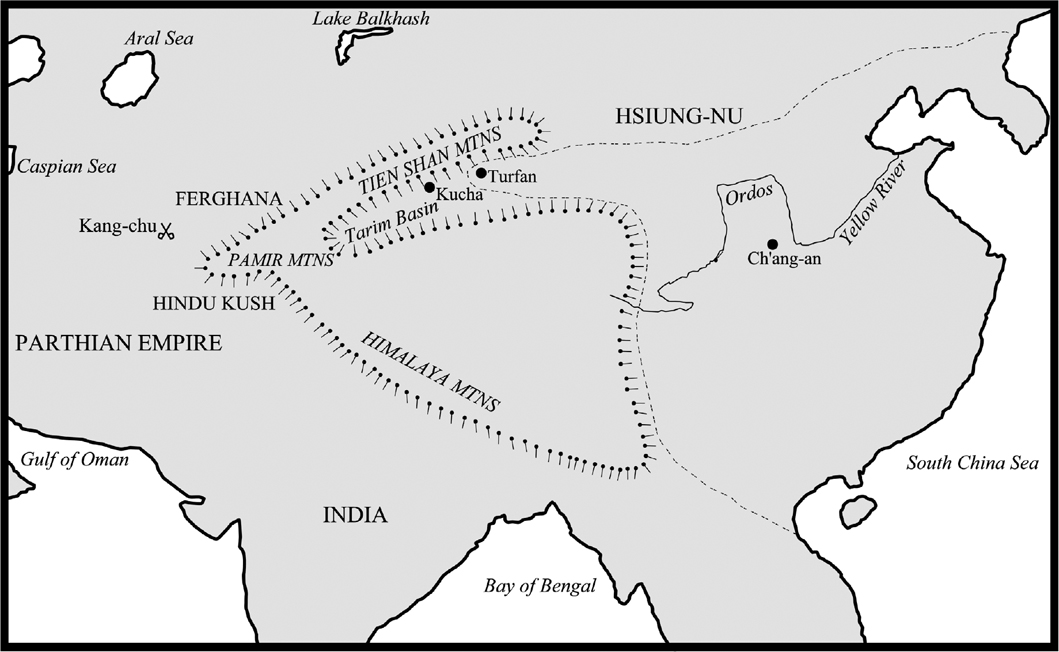

Central Asia in the Han period. The broken line indicates the approximate extent of the Western Han Empire, c. 100 BC.

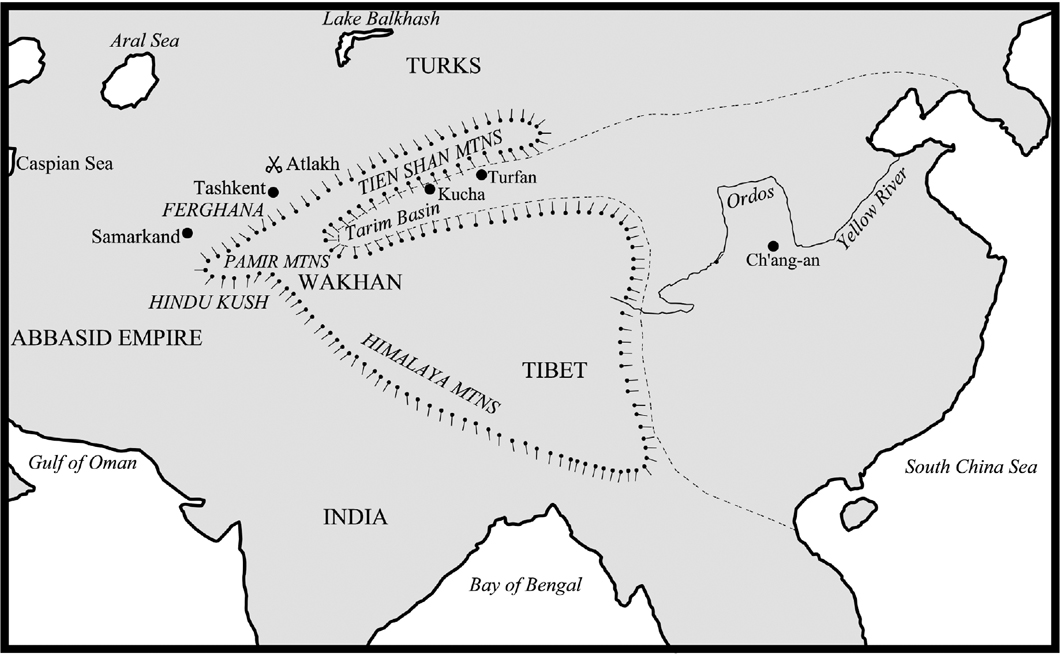

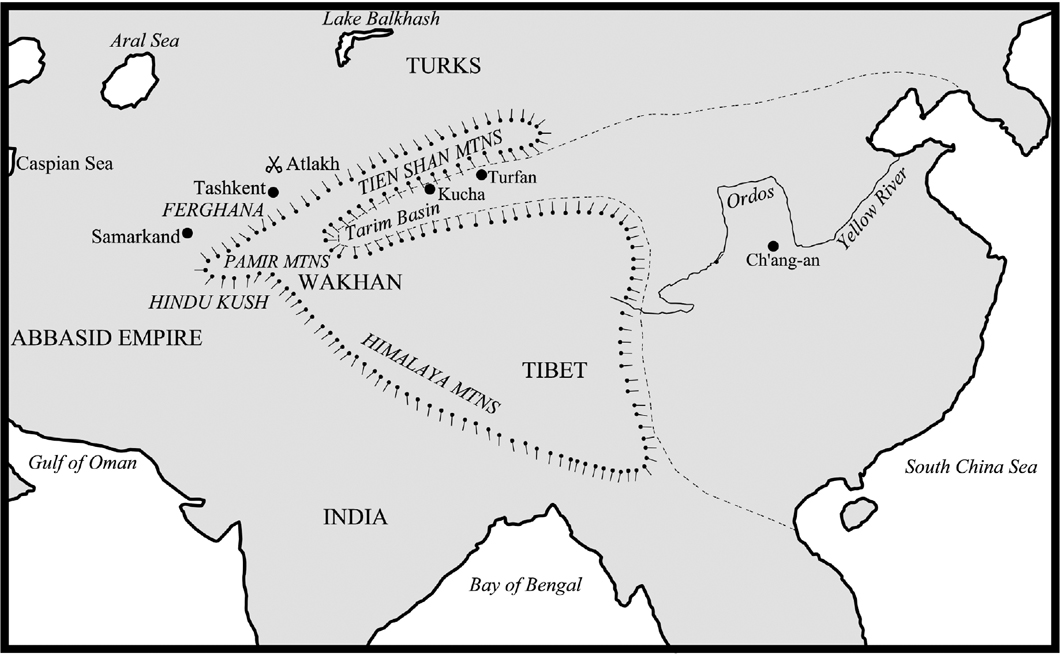

Central Asia in the Tang period. The broken line indicates the approximate extent of the Tang Empire, c. AD 750.

Introduction

Ancient China: History and Myth

I n the following chapters I intend to illustrate the evolution of the military art in ancient and medieval China with reference to ten battles or series of battles, and the campaigns which gave rise to them. They represent only a tiny fraction of the full scope of Chinese military history, but have been selected both for their historical importance and for the light which they shed on the weapons and tactics of the time. However the choice is also constrained by the limitations of the available sources. Chinese historical writing has been strongly influenced by the anti-military tradition which we associate with the great philosopher Confucius, and in the past many scholars did not consider the minutiae of military operations worth recording. There are several notable exceptions, but their coverage of events is often patchy, with the result that we can reconstruct a number of fairly minor actions in considerable detail, while our sources remain frustratingly vague about what we would regard as the pivotal events of the wars in question. For example, the relatively minor skirmish between Han troops and Hsiung-nu barbarians at Kang-chu in 36 BC is recounted at greater length than the far more extensive campaigns of Huo Chu-ping and others against the Hsiungnu-between 121 and 119 BC not because it was necessarily of greater historical significance, but because, as Michael Loewe points out in his study of military operations under the Han dynasty, Huos campaign went entirely according to plan, and so was subjected to less thorough analysis in official documents.

It is perhaps not surprising, in view of the linguistic and cultural barriers, that despite its recent rise to prominence on the world stage China remains a land of mystery to many in the west. A remarkable number of myths about Chinese history are still current. Of these, by far the most enduring concerns the Great Wall. In recent years several excellent studies, some of which are cited in the Bibliography, have tried to put this iconic structure into its true perspective, but it is still not uncommon to find popular works treating the Wall as if it had been a constant factor in Chinese strategy since the first millennium BC questioning, for example, how the Mongols could have got past it in the early thirteenth century, or even doubting the veracity of Marco Polo, who arrived in China overland later in the same century, because he does not mention it. So some readers may wonder why the Great Wall does not feature in any of the battles described in this book. The answer is simply that, at most of the periods with which we are concerned at least, it was not there. We know that the Emperor Shih Huang-ti of the Chin dynasty built a wall, or a series of walls, along the northern frontier of China at the end of the third century BC, but we cannot be sure what sort of obstacle it was, or exactly where it ran, or whether it was even a continuous barrier. In fact the emperors biographer Ssu-ma Chien, whose account is our main source for the Chin era, implies that it was not continuous, referring instead to a scheme which involved the fortifying of forty-four cities, the utilisation of natural mountain barriers, and the construction of earth ramparts at other points where they were needed. Some later dynasties also built fortifications mostly of earth rather than stone at various points along the frontier, but others, like the Tang, placed less emphasis on defensive measures, and allowed the works of their predecessors to fall into disrepair. The Wall as we know it today was constructed under the Ming dynasty in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries AD, and it runs far to the south of most of the earlier defensive lines none of which are likely to have been as formidable an obstacle as the modern stone structure, even when newly built.

Another related myth portrays the Chinese as a uniquely unmilitary people, who have always preferred to rely on technology or sheer cunning to overcome their enemies, rather than brute force. This ties in neatly with the idea of an isolationist civilisation hiding behind the Great Wall, and with the emphasis on deception and psychological warfare to be found in Sun Tzus famous classic on the Art of War, but as a generalisation it is highly misleading. It is true that the dominant ideology of Imperial China, as expressed in the fifth century BC by Confucius, emphasised , placed their emphasis on the unfitness to rule of the defeated Shang king, rather than on the innovative tactics which may in fact have been decisive on the battlefield. An often-quoted Han proverb describes a military career as a waste of talent comparable to using good quality iron to make nails. But the following chapters will show many examples of men who rose to power and fame, and even founded prestigious dynasties, by their success in war.

Next page