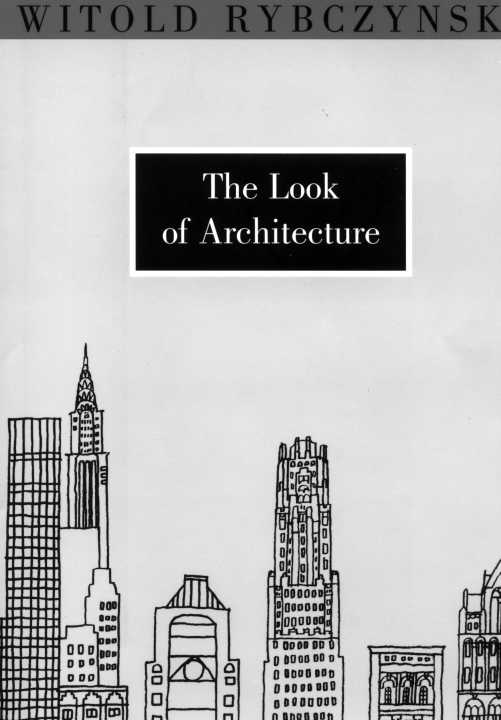

THE LOOK OF ARCHITECTURE

OTHER BOOKS BY WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI

One Good Turn: A Natural History of the Screwdriver and the Screw

A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the Nineteenth Century

A Place for Art: The Architecture of the National Gallery of Canada

City Life: Urban Expectations in a New World

Looking Around: A journey Through Architecture

Waiting for the Weekend

The Most Beautiful House in the World

Home: A Short History of an Idea

Taming the Tiger: The Struggle to Control Technology

Paper Heroes: Appropriate Technology, Panacea or Pipe-dream?

Each year the New York Public Library and Oxford University Press invite a prominent figure in the arts and letters to give a series of lectures on a topic of his or her choice. The lectures become the basis of a book jointly published by the Library and the Press. The previous books in the series are The Old World's New World by C. Vann Woodward; Culture of Complaint: The Fraying of America by Robert Hughes; Witches and Jesuits: Shakespeare's Macbeth by Garry Wills; Visions of the Future: The Distant Past, Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow by Robert Heilbroner, Doing Documentary Work by Robert Coles; and The Sun, the Genome, and the Internet by Freeman J. Dyson.

THE LOOK

OF ARCHITECTURE

Witold Rybczynski

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

To Peter Collins

Contents

xi

ONE

TWO

THREE

Introduction

Architects don't like to talk about style. Ask an architect what style he works in and you are likely to be met with a pained expression, or with silence. Press further, and you will provoke an exasperated denial: "Serious architecture has nothing to do with style." While a writer or a painter can be applauded for stylistic ability, calling an architect a stylist is considered faint praise. And nothing enrages an architect as much as being categorized according to a particular style. I have heard both Robert Venturi and Michael Graves bridle at the suggestion that their work had something to do with Postmodernism-of which both men are virtuoso practitioners. Most architects prefer to talk about massing and space, or context and historical allusions, or-if they are prone to academic jargon-about "tectonics" and "materiality." In other words, although architects are willing to accept the notion that buildings embody ideas, they don't like to acknowledge the manner in which these ideas are expressed.

Even a cursory glance at buildings of the recent past confirms that architectural style is real, and that, like style in dress or food, it changes with regularity. Different periods favor different materials: For example, glass-blocks belong to the 192os, and corrugated fiberglass marks the 1950s; we will likely remember the late 199os as the time that architects began wrapping buildings in zinc and titanium. The same is true for shapes and colors. There is no mistaking a cumbrous, monochrome prewar post office building, say, with its flimsy, pastel-colored Postmodern successor-the buildings, like stamps, have different styles.

One of the few modern architects early to face the issue of style was the iconoclastic Philip Johnson. "A style is not a set of rules or shackles, as some of my colleagues seem to think," he once said. "A style is a climate in which to operate, a springboard to leap further into the air." In 1932, Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock pointedly described the new architecture of flat-roofs, white rectilinear facades, and ship-railing balconies as the International Style. At the time, Johnson was an architectural historian; practitioners themselves bridled at being associated with something so trivial. "Style is like a feather in a woman's hat, nothing more," sniffed Le Corbusier. Gabrielle Chanel, who knew something about women's hats, saw things differently. "Fashion passes," she said, "style remains."

I agree with Chanel. It seems to me that style is one of the enduring-and endearing-aspects of architecture. Architects are being naive in denying validity to the concept of style. They are also being dishonest, since most successful practitioners are acutely conscious of style-and not only in their designs. How else to characterize Frank Lloyd Wright's capes and pork-pie hats, Le Corbusier's round eyeglasses, and Louis Kahn's bow ties, except as evocations of personal style? Even Frank Gehry's rumpled suits are a kind of style. In fact, most of the architects I know are preoccupied with style-not only in dress, but in furniture, automobiles, even pens (the cigarlike Mont Blanc Meisterstiick being the favorite). Why are they unwilling to acknowledge the obvious?

I have explored tentatively the subjects of style in essays and book reviews over the years. My first public lecture on dress and decor was at the 1994 International Design Conference at Aspen, later repeated at Colonial Williamsburg. I was given the opportunity to bring this material together in a considered manner when I was invited to give a series of public lectures under the auspices of Oxford University Press and the New York Public Library. I delivered the lec tures in the Celeste Bartos Forum of the Library on three successive Tuesday evenings in October 1999. This book is the result. It is organized in three parts, which reflects the course of the lectures. However, the spoken and written word differ. This book is not a transcription of what was, in any case, an extemporaneous series of talks. I have taken the opportunity to elaborate ideas, which I previously merely alluded to. Reflection and some pointed questions from an attentive audience have caused me to reconsider certain statements. The text has been enriched further by conversations with practitioners, notably Jaquelin T. Robertson and Robert A. M. Stern. It was the latter who reminded me that Oscar Wilde once remarked, "In matters of importance, style is everything."

THE LOOK OF ARCHITECTURE

ONE

DRESSING UP

rchitecture is hard to define. Goethe called it music frozen in space, which, while it captures a sense of rhythm, is too one-dimensional. And it relegates the mother of the arts to an inferior position; just as well to describe music as melted architecture. Nietzsche believed that architecture reflected his pride, man's triumph over gravity, and his will to power. This notion applies to many buildings, from Gothic cathedrals to skyscrapers, but it is too, well, Nietzschean. The British master Edwin Lutyens referred to architecture as a sort of play: "In architecture, Palladio is the game!" Le Corbusier described his art as "the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light," which is a good description of one of his own buildings. I am partial to Sir Henry Wotton's definition. Wotton, who lived a long time in Venice and was a lover of architecture though not an architect, published a treatise on the subject in 1642. "In Architecture, as in all other Operative Arts, the end must direct the Operation," he wrote. "The end is to build well. Well-building hath three conditions: Commoditie, Firmeness, and Delight."

rchitecture is hard to define. Goethe called it music frozen in space, which, while it captures a sense of rhythm, is too one-dimensional. And it relegates the mother of the arts to an inferior position; just as well to describe music as melted architecture. Nietzsche believed that architecture reflected his pride, man's triumph over gravity, and his will to power. This notion applies to many buildings, from Gothic cathedrals to skyscrapers, but it is too, well, Nietzschean. The British master Edwin Lutyens referred to architecture as a sort of play: "In architecture, Palladio is the game!" Le Corbusier described his art as "the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light," which is a good description of one of his own buildings. I am partial to Sir Henry Wotton's definition. Wotton, who lived a long time in Venice and was a lover of architecture though not an architect, published a treatise on the subject in 1642. "In Architecture, as in all other Operative Arts, the end must direct the Operation," he wrote. "The end is to build well. Well-building hath three conditions: Commoditie, Firmeness, and Delight."

rchitecture is hard to define. Goethe called it music frozen in space, which, while it captures a sense of rhythm, is too one-dimensional. And it relegates the mother of the arts to an inferior position; just as well to describe music as melted architecture. Nietzsche believed that architecture reflected his pride, man's triumph over gravity, and his will to power. This notion applies to many buildings, from Gothic cathedrals to skyscrapers, but it is too, well, Nietzschean. The British master Edwin Lutyens referred to architecture as a sort of play: "In architecture, Palladio is the game!" Le Corbusier described his art as "the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light," which is a good description of one of his own buildings. I am partial to Sir Henry Wotton's definition. Wotton, who lived a long time in Venice and was a lover of architecture though not an architect, published a treatise on the subject in 1642. "In Architecture, as in all other Operative Arts, the end must direct the Operation," he wrote. "The end is to build well. Well-building hath three conditions: Commoditie, Firmeness, and Delight."

rchitecture is hard to define. Goethe called it music frozen in space, which, while it captures a sense of rhythm, is too one-dimensional. And it relegates the mother of the arts to an inferior position; just as well to describe music as melted architecture. Nietzsche believed that architecture reflected his pride, man's triumph over gravity, and his will to power. This notion applies to many buildings, from Gothic cathedrals to skyscrapers, but it is too, well, Nietzschean. The British master Edwin Lutyens referred to architecture as a sort of play: "In architecture, Palladio is the game!" Le Corbusier described his art as "the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light," which is a good description of one of his own buildings. I am partial to Sir Henry Wotton's definition. Wotton, who lived a long time in Venice and was a lover of architecture though not an architect, published a treatise on the subject in 1642. "In Architecture, as in all other Operative Arts, the end must direct the Operation," he wrote. "The end is to build well. Well-building hath three conditions: Commoditie, Firmeness, and Delight."