TOWARDS A NEW ARCHITECTURE

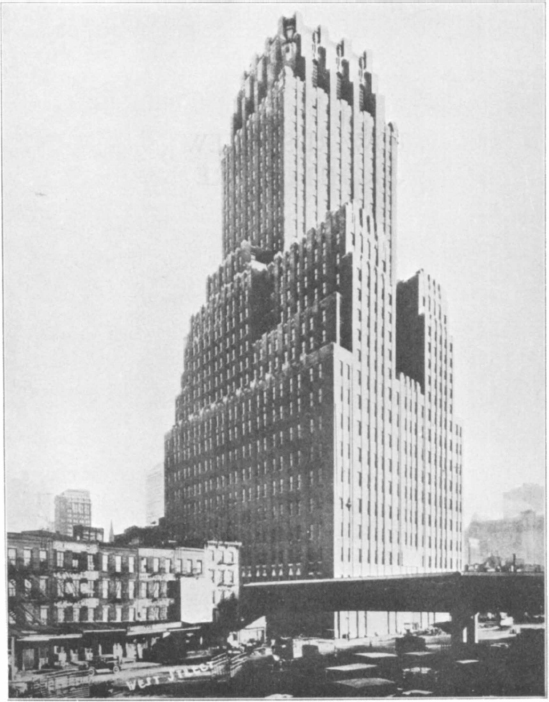

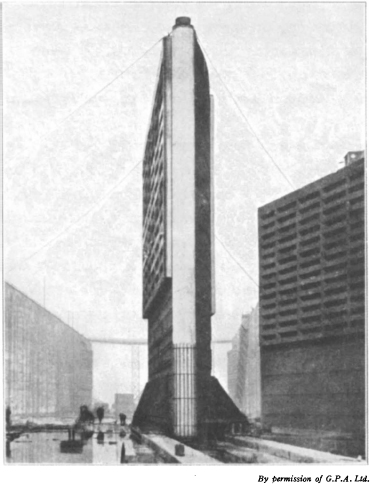

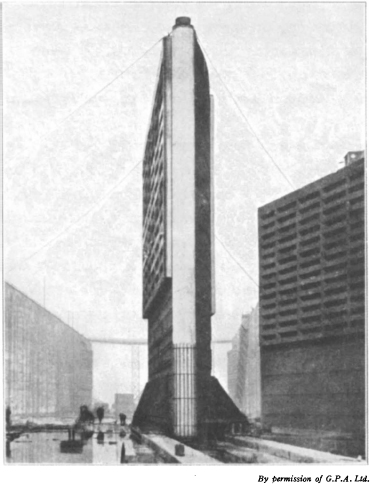

THE TELEPHONE BUILDING, NEW YORK

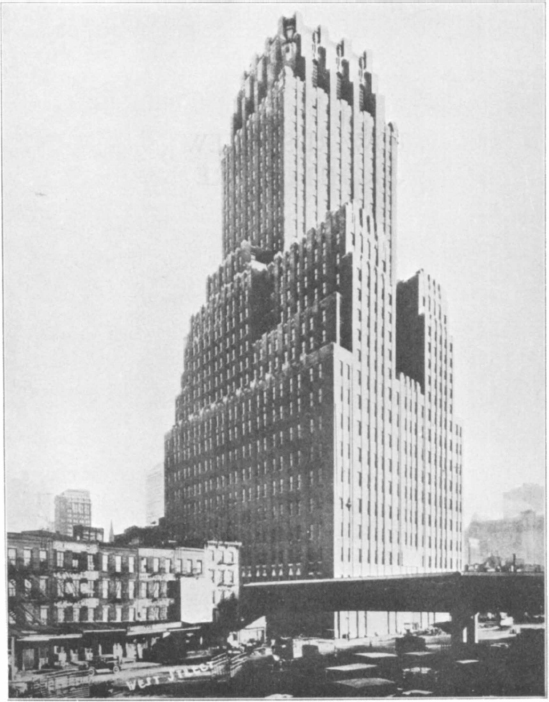

TOWARDS A NEW ARCHITECTURE

by

LE CORBUSIER

Translated from the thirteenth French edition and with an Introduction by

FREDERICK ETCHELLS

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

New York

This Dover edition, first published in 1986, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the work originally published by John Rodker, London, in 1931, as translated from the thirteenth French edition and given an English introduction by Frederick Etchells.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Le Corbusier, 1887-1965.

Towards a new architecture.

Reprint. Originally published: London: J. Rodker, 1931.

1. Architecture. 2. Functionalism (Architecture). I. Title.

NA2520.L3613 1986 720 85-20468

ISBN 0-486-25023-7

INTRODUCTION

Say not thou, What is the cause that the former days were better than these?

Eccles. vii. 10.

A MAN of the eighteenth century, plunged suddenly into our civilisation, might well have the impression of something akin to a nightmare.

A man of the nineties, looking at much of modern European painting, might well have the impression of something akin to a nightmare.

A man of to-day, reading this book, may have the impression of something akin to a nightmare. Many of our most cherished ideas in regard to the Englishmans castlethe lichened tiled roof, the gabled house, patinaare treated as toys to be discarded, and we are offered instead human warrens of sixty storeys, the concrete house hard and clean, fittings as coldly efficient as those of a ships cabin or of a motor-car, and the standardized products of mass production throughout.

We need not be unduly alarmed. All the inventions that go to make up our modern civilization, so far as it has gone, have awakened the same terrors. The railway, it was prophesied, would ruin the countryside, the motor-car the roads, and the airplane the upper air. All these things have happened, and to a large extent the criticisms were true, and yet man still survives and carries on, and seems happy or unhappy to much the same degree asbefore. The truth is that man has an uncanny faculty of adapting himself to new conditions. He learns to admit and even, in a sneaking sort of way, to like new and strange forms. The new form is at first repugnant, but if it has any real vitality and justification it becomes a friend. The merely fantastic soon dies.

Now, in modern mechanical engineering, forms seem to be developed mainly in accordance with function. The designer or inventor probably does not concern himself directly with what the final appearance may be, and probably does not consciously care. But men are endowed in varying degree with an instinct for ordered arrangement, and this can come into operation even when least thought of. The ordinary motor-car engine is a conspicuous example of this. Some are disorderly and messy in arrangement; others well planned and cleanly disposed.

In structural engineering the same thing appears. The modern concrete bridge or dam may be a crude and ungainly affair, or it may possess its own grave and stark beauty; the structure being equally good and functional in either case.

It is inevitable that the engineer, preoccupied with function and aiming at an immediate response to new demands, should produce new and strange forms, often startling at first, bizarre and disagreeable. Some of these forms are not worth constant repetition and soon disappear into the limbo of forgotten things. Others stand the test of use and standardization, become friendly to us and take their place as part of our general equipment. And these good new forms, so foreign to us and so disturbing at first view, are seen in the long run to have a curious affinity with those of a similar function in any good period of history.

The engineer and the architect have to work with other peoples money. They must consider their clients and, like politicians, cannot be too far ahead of their moment. The artist, on the other hand, particularly the painter, may generally find it nearly impossible tolive; but if he is able to establish one of those curious compromises by means of which he can carry on a lean existence, he is at least free (at times) to project himself on paper or canvas without necessary reference to anything or anybody; and to make experiment and research for its own sake. This passion, renewed in our own day by, it is true, a comparatively small body of artists, has resulted in that disconcerting but formidable body of work which angers unnecessarily so many people.

LIVERPOOL. ENTRANCE GATE TO NEW LOCK

The photograph shows one leaf of the new river entrance lock being moved into position on timber launchways. The gates are closed by wire rope attachments. This leaf alone weighs 500 tons, and the gates will be the largest in the world.

The modern engineer, then, pursues function first and form second, but it is difficult for him to avoid results that are plastically good. The good modern painter pursues plastic form for its own sake, and if he has the necessary ability the results are plastically satisfying.

These things are true of the modern engineer and the painter. Are they true of the architect, who in some ways combines the functions of both? M. Le Corbusier would emphatically tell us No!His book is a challenge to the members of his own profession. He writes, that is to say, as an architect for architects, and as a scholar always with an eye on the work of the great periods; and he writes more in sorrow than in anger! He is no fauve, no revolutionary, but a sober-minded thinker inspired by a fierce austerity. Towards a New Architecture was written, of course, originally for French readers, and there are points in it which obviously have not the same force applied to conditions in England or America; but the book strange paths we are likely to be forced to travel whether we will or no.

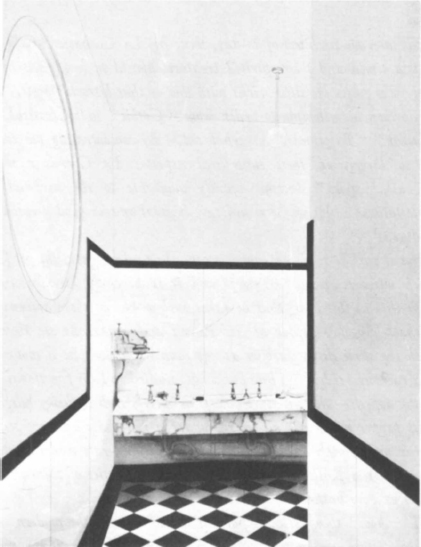

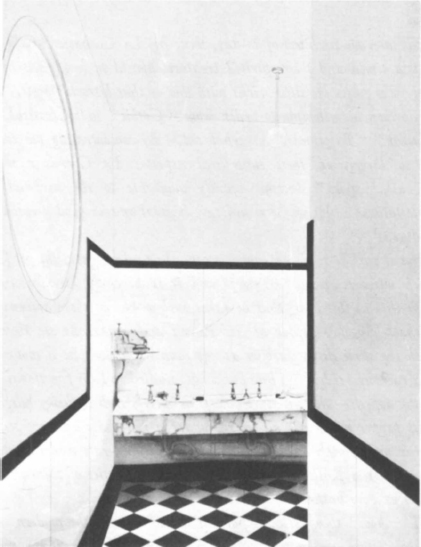

MODERN SYNTHETIC MATERIALS MEWS & DAVIS, F.F.R.I.B.A., ARCHITECTS.

The average architect of to-day, then, M. Le Corbusier would tell us, is a timid and poor-spirited creature, afraid to look facts in the face. He plays his little tricks with this or that historic style, and he can turn his attention to order from Gothic to Classical, to Tudor, Byzantine, or what not. By concentrating his training so largely on these superficial aspects, Le Corbusier would say, all styles become equally available to the architect for exploitation. Not so, he would say, is great or even good architecture produced.

But it will be said, we cannot escape the past or ignore the pit from which we were hewn. True; and it is precisely Le Corbusiers originality in this book that he takes such works as the Parthenon or Michael Angelos Apses at St. Peters and makes us see them in much the same direct fashion as any man might look at a motor-car or a railway bridge. These buildings, studied in their functional and plastic aspects

Next page