The City of To-morrow

AND ITS PLANNING

By kind permission of Aerofilms, Ltd.

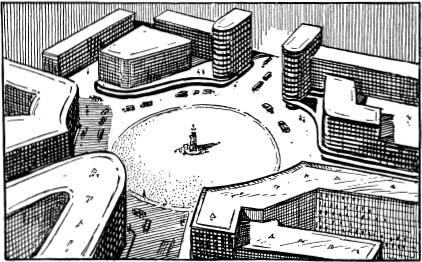

A LONDON SUBURB

The town spread out over an immense area. Narrow corridor streets. Back gardens that are little more than yards.

The City of To-morrow

AND ITS PLANNING

by LE CORBUSIER

translated from the 8th French Edition

of URBANISME with an introduction by

FREDERICK ETCHELLS

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

This Dover edition, first published in 1987, is an unabridged and slightly altered republication of the work originally published by Payson & Clarke Ltd, New York, n.d. [1929], as translated from the eighth French edition of Urbanisme and given an introduction by Frederick Etchells. The plans facing pages 176 and 177 were originally printed on a foldout; they have been printed over six consecutive pages for this edition. The illustration on page 276 and facing page was originally partially in color.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Le Corbusier, 18871965.

The city of to-morrow and its planning.

Translation of: Urbanisme.

1. City planningForecasting. 2. City planningHistory20th century. I. Title.

NA9095.L413 1987 711.40904 86-24342

ISBN 0-486-25332-5

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

25332509

www.doverpublications.com

INTRODUCTION

I N Le Corbusiers Book, Vers une Architecture, he set forth fully his general conception of architecture, both on the sthetic and on the constructional side. It is not altogether an easy book, yet the questions of which it treats are such as touch, at some point or other, the lives of every one of us, quite apart from matters which are likely to interest primarily the specialist. But interest in architecture to-day, at any rate in this country, is too often confined to what is pretty or cosy or picturesque; pleasant enough things in their way but not of the essence of good building. The excursions into the study of serious architectural forms which were a part of the necessary education of the cultivated eighteenth century gentleman must have helped, one imagines, to make that amazing age what it was.

This volume has a more immediate appeal to the ordinary citizen. It is true enough that the ugliness of the houses in which they live does not unduly depress the bulk of people, and it is easier to touch them on the point of amenities such as constant hot water or electricity than on questions of proportions and relationships of architectural forms. But nearly every town-dweller knows well what it is to wait in a queue for a bus on a wet evening, or to fight for entrance into a tube carriage at the rush hour; or to crawl along Oxford Street in a taxione of the most desolating experiences possible.

Here the author has undertaken a close survey of the existing conditions in our great cities and of their functioning under the new state of things which has arisen since the present machine age began ; and particularly, of course, in relation to mechanical transport. I shall mention later on the three vital topics with which he deals, the Street, Housing and Open Spaces in the great town. But it should be clear that the subject is one that touches us all, and closely. It is essential to town-dwellers that they should be appropriately and decently housed, that they should be able to get about their city in reasonable comfort, that light and air and provision for out-of-door exercise and recreation should be assured them, not to mention such services as sanitation, gas, electricity and water.

Le Corbusier began by tracing the origins of cities and the causes which have led to the state of chaos in which we find ourselves. As against the nomads camp, or the little collection of huts from which so many cities have sprung, he recalls town planning of the past, such as Babylon, the Roman colonial towns, Pekin, the mediaval fortified towns and the great works carried out under Louis the Fourteenth. All these were geometrical, predetermined and ordered lay-outs, in sharp contrast with the ordinary European mediaval townwith its narrow winding streets and picturesque jumble. It is this latter type of town which has in most cases determined the existing state of our cities. The City of London itself is a conspicuous example.

Few Englishmen are likely to be insensible to the charm of what is accidental or picturesque or a little haphazard ! The sensation of pleasure that an old village, for example, can cause us to feel is due partly, I suppose, to this element and partly to the beauty of patina and to that curious quality of rightness of things that have merely happened, as one can see in the case of a tea-tray where the crockery has been shifted about a little in use. But that is only one side of the picture ; there is a positive, and one would think a more sober and important, side of the human mind, which insists instinctively on the tidying-up of chaotic conditions. This is the instinct for Order.

This book deals strictly with urban conditions, and its main thesis is that such a vast and complicated machine as the modern great city can only be made adequately to function on a basis of strict order. We are to forgo, or to relegate to a minor place, pleasures arising out of picturesqueness or of what is merely pretty or wilful, and to confine ourselves to the sterner delights which severe and pure forms can give us. We are to aim first of all at efficiency, for that is the crying need of the moment, but it must lead us on to a fine and noble architecture.

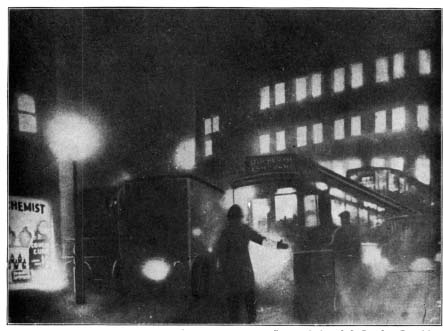

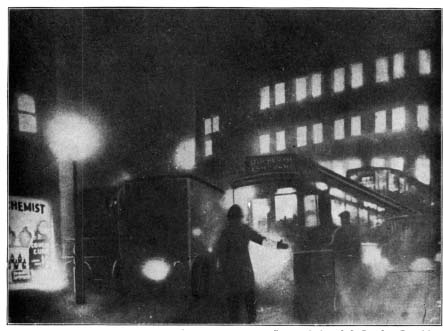

By permission of the Sunday Graphic.

A FOGGY DAY IN LONDON

Under such conditions all ideas of roof gardens, terrace gardens and indeed all outdoor amenities become ridiculous. The smoke nuisance must be eliminated as a first step.

The fog tonnage over London is 70 to 200, according to its density. The damage to health is estimated at 125,000, extra lighting and heating costs 275,000, wage losses amount to 150,000, goods delayed in transit mean a loss of 150,000, and the derangement of everybodys affairs costs no less than 300,000.

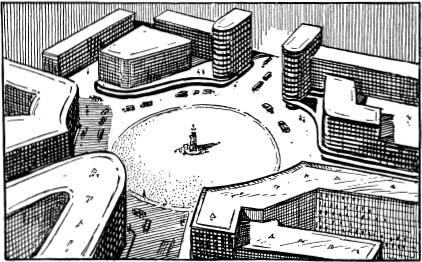

Now, if for a moment we look at our great citiesat London, if you likeas machines, we shall find that they do not function as they ought to ; I think this is common ground. The inhabitants, except for a fortunate few, are inadequately and uncomfortably housed, and traffic is a chaos. There are, as regards the buildings, a few picturesque survivals and a mass of fine eighteenth century architecture, but for the most part the existing structures are mean and unworthy. The whole urban scene is one of wasted opportunities and inefficiency.

If we consider the question of how the modern city is to be made to function under the conditions of to-day, we shall find ourselves forced to take sides at once. We may agree to carry on with the present methods of a little tidying-up here and there, the widening of an existing street or the provision of a new one, in the hope that these costly palliatives may cure the evil. But this seems to many of us a forlorn hope, and it must be admitted that the results have not, so far, been encouraging.

Next page