First published in Australia in 2011

Copyright Sarah Maddison 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

978 1 74237 328 7

Typeset and ePub production by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Let no one say the past is dead.

The past is all about us and within.

From The Past, by Oodgeroo Noonuccal, 1970

Contents

Foreword

n 2010 I launched an exhibition at the Australian Museum in Sydney. It contained works by the noted Aboriginal artist, Gordon Syron. A few days earlier, I had been invited by Gordon to visit the Keeping Place, a large space near the Everleigh train sheds in which he and his wife maintained their unique collection of art by Aboriginal painters.

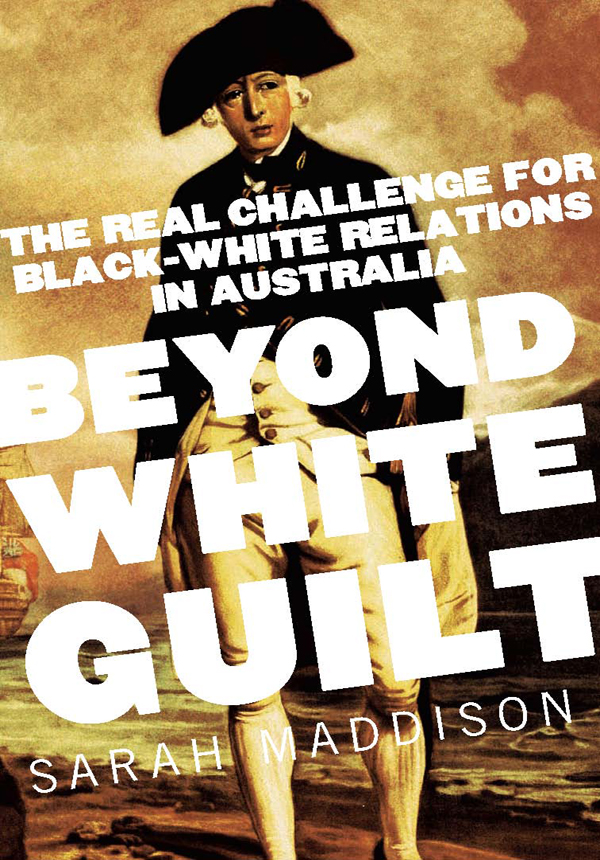

One painting in the collection caught my eye. It was part of a series that Gordon had produced, over the years, showing the fateful meeting between the ships of Governor Arthur Phillips First Fleet, arriving off the heads of what is now Sydney Harbour, and a lone Aboriginal witness. He seems to stand defiantly on the water, confronting the ghostly vessels with their portents of change.

Executed in beautiful colours of dark blue and pale white, the painting was arresting both in its concept and its execution. Gordon Syrons most famous painting portrayed a courtroom in which all the actors (bewigged judge and barristers, the jury and attendants, clerks and members of the public) were black. Only the accused, sitting in the dock was white. It was a powerful allegory. And yet the sombre confrontation of vessels and witness on the January day in 1788 bore a more subtle message: What if?

What if the British officials had been more attentive to the demands of the American colonists? What if they had quickly given away their obduracy and agreed to accord to their American cousins rights equal to those enjoyed by Englishmen at home? What if the need to find an alternative dumping ground for the British convicts had evaporated, so that there was no requirement to send the prisoners to the far-off coast that James Cook and Joseph Banks had reported in 1771? What if Phillip and his captains had got lost on the long journey? What if they had succumbed, as so many Netherlands vessels did, to the dangers of the Roaring Forties or the perils of landfall in Australia? What if Phillip had not been such a skilled commander but had lost his human cargo to disease or mutiny? What if he had quickly suffered the failure in his large project in Sydney town? What if they had not explored Farm Cove and, in search of water, had pressed on to the New Zealand? What if, on arrival at Farm Cove, Phillip or his successors had negotiated a treaty with the original inhabitants, acknowledging and respecting their rights, treating them as the first peoples, as would later be done at Waitangi? What if the Aboriginals and other indigenes had been more numerous? More warlike? Less transfixed and overwhelmed by the astonishing vessels off the heads, with their pale human cargo and well-armed redcoats?

All of these questions are futile today because we know what happened. The First Fleet laid anchor in the pristine solitude of one of the largest and most beautiful spaces of water in the world. The home reports that followed made Australia a beckoning attraction to the waves of migration that have continued, right up to the present time. The droughts and flooding rains have hardly caused in a dent in the ongoing arrivals of humanity that pour into the Great South Land searching for adventures, opportunities and human happiness.

Of course, many of those who have arrived have suffered pain and disappointment. But the chief disruption, as events turned out, was for that first solitary Aboriginal witness and his descendants. This book lays out the way modern Australia can right the wrongs that have occurred in the intervening years, and decades, and centuries that have passed since that first dramatic encounter.

In the middle of this book, the author tells of an exchange she had with the great Australian philosopher, Peter Singer. She records, with candour, that at a conference he accused her of being inadequately concerned with the real-life challenges confronting Aboriginal women and children in the here and now. No doubt, there will be readers of this book who will likewise roll their eyes at its title and put down its pages with distaste and exasperation. Rejecting the thought that they are racists. Embracing the idea that they live in a land of the fair go. Clinging to the notion that it is completely unnecessary to re-live the moments when British power and Aboriginal presence confronted each other on the fateful shore of Sydney Harbour. As Sarah Maddison repeatedly explains, the Australian reaction to the indigenous people of the continent has been ambivalent from the first. Most of the newcomers hoped to find, in the image of the country they grew up in, or later adopted as their own, honourable stories of good deeds, generous acts and magnanimous engagement with others.

Whilst there had been such events in the evolution of Australian nationhood, a defect quickly arose in our relations with the first peoples. Many were killed for daring to protect their lands, possessions and families against the onrush of the explorers and settlers. Quite quickly, the legal system rejected their claims for acknowledgement of land rights. It denied respect for the culture and traditions of their Aboriginal forebears. They were not eliminated in the kind of genocidal extermination pursued by the Nazi rulers of Germany. But they were certainly denied true equality; many driven to the outskirts of townships; exposed to crippling diseases; introduced to the debilitations of alcohol; and effectively kept from the benefits of modern shelter, education and health care. Equal pay (or pay at all) was very slow in coming to them. Few indeed were admitted to universities, the professions, or leadership opportunities. The Constitution itself for a long time contained disparagements, notions of assimilation and elimination of cultural identity. For generations, these represented the accepted policy of successive Australian governments. In the long term, it was expected, the Aboriginal problem would simply disappear because they would die out and be fully assimilated.

Although by the 1970s, this story of deprivation began to change, the authors thesis is that the change has been too slow. It has not been whole-hearted. It is deeply flawed by a stubborn refusal of white Australia to acknowledge the wrongs, so that we can all move beyond unarticulated feelings, collective guilt and discomfort into a true sense of solidarity and community with Aboriginal brothers and sisters. This will not happen, it is suggested, so long as Australians cling to the notion that everything has been fixed up. That the tide has turned. That reconciliation has been achieved. That a national apology has been given. And that enormous advances have been accomplished in land rights, shelter, education, health and opportunities.