Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

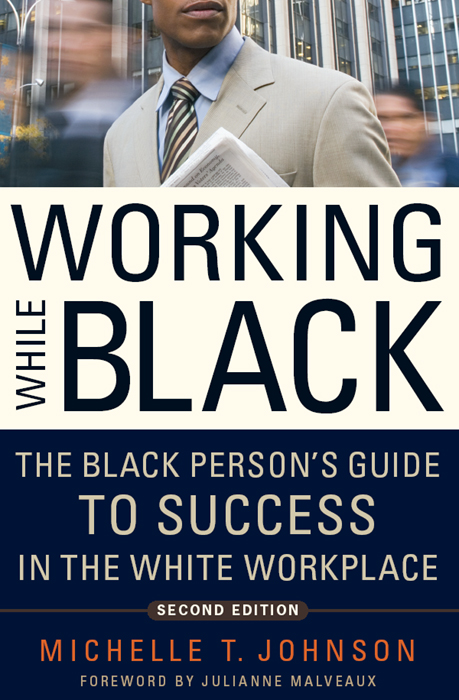

Johnson, Michelle T.

Working while black : the black persons guide to success in the white workplace / Michelle T. Johnson. 2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56976-346-9 (pbk.)

1. African AmericansEmploymentPsychological aspects. 2. Success in business. I. Title.

HD8081.A65J64 2010

650.1089'96073dc22

2010027728

Cover and interior design: Monica Baziuk

Cover photo: PBNJ Productions/Blend Images/Getty Images

Typesetting: Jonathan Hahn

2004, 2011 by Michelle T. Johnson

Foreword 2011 by Julianne Malveaux

All rights reserved

Second edition

Published by Lawrence Hill Books

An imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-56976-346-9

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to all the ancestors who made the opportunities possible, and to the descendants who endure and made the book necessary to write.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

W ITH THE SECOND EDITION of this book comes another group of supporters who helped make my writing and serving happen. So along with my stalwart supporters Ethel, Cliffie, Adrienne, and many others, I would particularly like to thank Ora Stafford, Jahi Boseda, and Joy Springfield.

DISCLAIMER

Every incident, person, and example in this book is either a true story or based on a true story. Because of the nature of my job as a mediator and former employment attorney in a law firm (and because I have friends and associates who will hunt me down), names are not used and, when necessary, identifying details are changed to protect privacy.

This is not, I repeat, not legal advice. Please do not let any comments in this book serve as your sole or motivating basis for doing or saying anything that will have legal ramifications. If you really think youve got a problem, talk to a friend, a counselor, a spiritual adviser, or an attorney and get advice from a professional who knows the specific facts of your situation. Refer to the resources in the back of this book for further assistance and inspiration.

FOREWORD

Julianne Malveaux

Without work all life is rotten, wrote the French novelist and essayist Albert Camus. But when work is soulless, life stifles and dies. I cannot read the Camus quote without thinking of the centrality of work in our lives and the many ways work has evolved from simply a means for survival and sustenance into something that infuses significant meaning in our lives. To be sure, most Americans must work in order to survivedespite the unequal distribution of wealth, only a small percentage of us are trust fund babies. For many of us, the workplace is the place where we spend a third of our lives, form relationships, develop social networks, search for meaning, and make a contribution to the world. Work doesnt always work. Men and women struggle with balancing work and family, many chafe under unsafe and unfair working conditions, others come face to face with discrimination in the workplace, and millions strain to find work because they both want and need it.

The workplace, then, is a complex place for most of those who inhabit it in good times and all the more challenging during this Great Recession, when the threat of layoffs and reorganization adds nuance to existing challenges. Furthermore, the workplace has been transforming for the past several decades. Instead of holding career jobs, todays average learner will have fourteen jobs by age thirty-eight, or a new job every year and a half. Globalization, the proliferation of technology, and demographic shifts have made the workplace far more competitive. And people continue to work because they must, both for survival and meaning.

What happens when you add race to the contemporary workplace? Michelle Johnson offers sociopolitical observations, advice, helpful workplace tips, and old-fashioned mother wit in this absorbing book. Being black is a full-time job, she observes, and you dont even get paid for it. While you wont get paid, you will pay, she says, and then delineates the many ways that African American workers pay the black tax on the job. Johnson acknowledges that the workplace is challenging for everyone, and 85 percent of the African American work experience is similar to that of others. The rub is the remaining 15 percent, those differences that are often unspoken and unacknowledged but painfully real for those who experience them. In unpacking the 15 percent, Johnson has produced a must-read for African American job seekers, those facing employment challenges, and those seeking to understand their own work styles. She divides black workers into survivors, strivers, thrivers, and drivers and contrasts the ways these folks might deal with race matters in the workplace. This useful division of work motivations makes this book also helpful for those who, regardless of race, want to understand the actions and reactions of their fellow workers and employees.

Why is a book like this needed in a so-called post-racial era? The answer, of course, is that we are not post-racial yet. In the employment arena, during this Great Recession, this is confirmed by data that shows, for example, that in June 2010 the unemployment rate for whites was 8.6 percent but nearly twice as high, 15.6 percent, for African Americans. It is confirmed by academic studies that show that Tammy is more likely to get a job than Tamika. The mean income among African Americans is still just 60 percent of white median income, and even when African Americans and whites have identical educations and work experience, there is an income gap.

The hard data suggest that the work experience for African Americans and whites is different, and subjective perceptions of the national climate underscore the suggestion. Consider the Shirley Sherrod case, in which an African American employee of the Department of Agriculture was unjustly accused of racism after a rogue Tea Party activist released a badly edited tape that seemed to show her making a loaded racial statement. In less than seventy-two hours she was fired, offered her job back, and given a presidential apology. The incendiary nature of the race debate is such that smug whites used her out-of-context comments as an example of reverse racism, while some hasty African Americans, eager to please, condemned Sherrod as quickly as whites did without bothering to hear the whole story. This story dominated the airwaves for nearly a week. What was the watercooler conversation around it? While the Sherrod situation may have had little to do with the work that any individual does, the heat around it must have seeped into some workplaces. Are there risks and rewards for black and white workers in engaging in conversations about controversial issues? Will opinions casually offered be used later to influence decisions about retention or promotion? Must African American workers withhold our opinions or stifle disagreement about the issues for which we feel passion? Working while black sometimes requires walking a tightrope, with less freedom than others have to simply be.