Contents

Guide

Page List

Further Praise for

Self-Portrait in Black and White

This small book poses a very large question: How to become a self? Thomas Chatterton Williams uses his own story to remind us that inner freedom depends on escaping the insidious categories of history and the suffocating clichs of the present. It is a stirring call to genuine liberation.

MARK LILLA, AUTHOR OF THE ONCE AND FUTURE LIBERAL

In fifty years, smart students will be writing senior theses seeking to understand why anyone in the early twenty-first century found anything in Self-Portrait in Black and White at all controversial. For now, curl up with this book to join a conversation on race about progress rather than piety, thought rather than therapy.

JOHN H. MCWHORTER, AUTHOR OF THE CREOLE DEBATE

This moving and engrossing memoir is unfashionable in the best of ways. At a time when even purportedly optimistic visions of the future seem to assume that Americans will always be defined by the color of their skin, Thomas Chatterton Williams makes us dream of a future in which the importance of race will recede, and we are finally able to love each other for who we truly are. An energizing book by one of the greatest writers of our time.

YASCHA MOUNK, AUTHOR OF THE PEOPLE VS. DEMOCRACY

ALSO BY

THOMAS CHATTERTON WILLIAMS

Losing My Cool

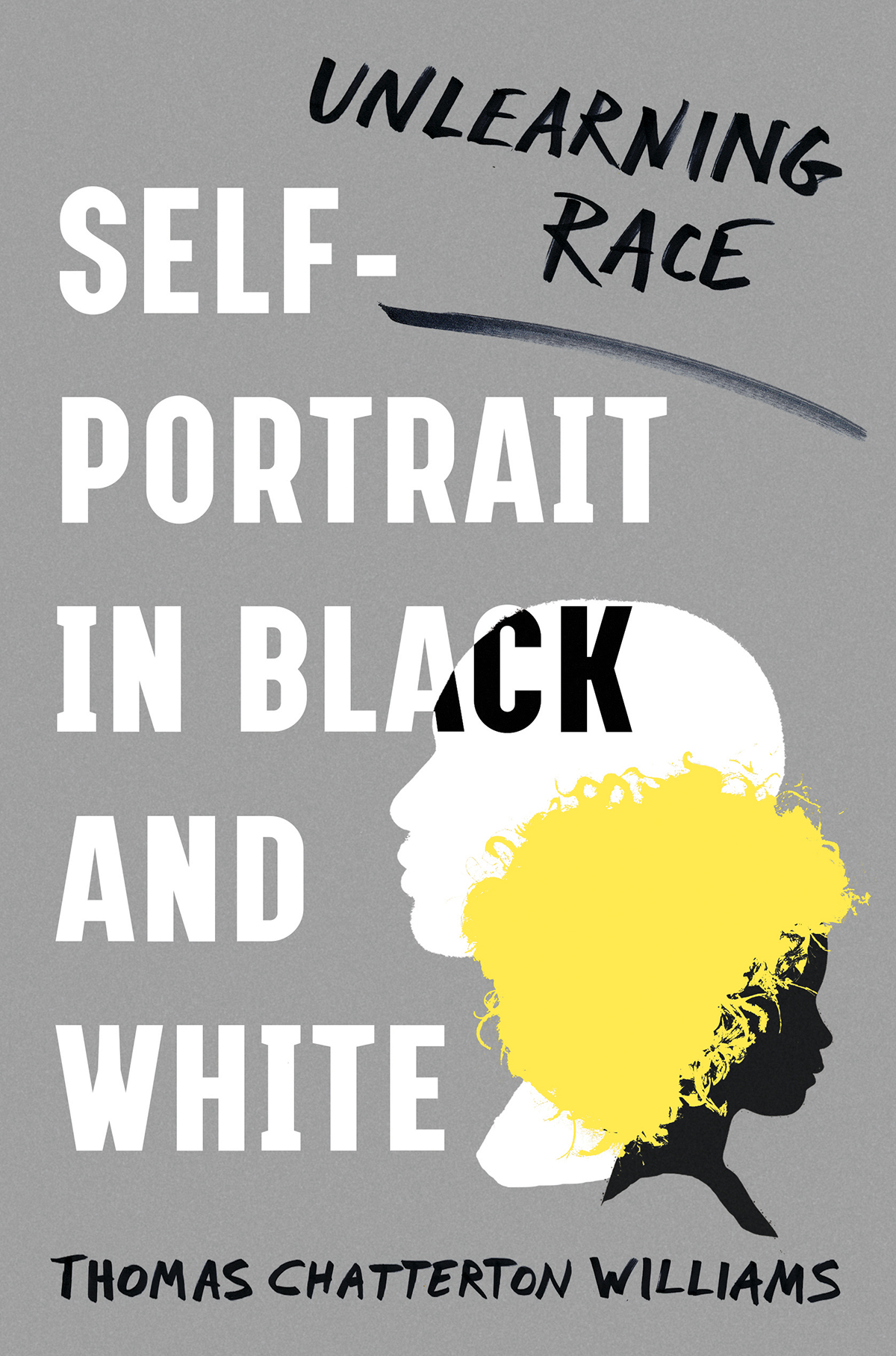

SELF-PORTRAIT IN BLACK AND WHITE

UNLEARNING RACE

THOMAS CHATTERTON WILLIAMS

For

MARLOW AND SAUL,

WHO HAVE TAUGHT ME

NEW WAYS TO SEE.

It was necessary to hold on to the things that mattered. The dead man mattered, the new life mattered; blackness and whiteness did not matter; to believe that they did was to acquiesce in ones own destruction.

JAMES BALDWIN, NOTES OF A NATIVE SON

Why waste time creating a conscience for something that doesnt exist?

For, you see, blood and skin do not think!

RALPH ELLISON, INVISIBLE MAN

CONTENTS

I HAVE TRIED TO CAST DOUBT ON AND REJECT TERMS (AND their synonyms) such as white, black, mixed, biracial, Asian, Latino, monoracial, etc., throughout this text. In so doing, I have frequently placed them in quotation marks. But for comprehensibilitys sake, inevitably I also have to fall back on our languages descriptive conventions, identifying people in some instances as they are commonly understood. If I use these terms and do not place them within quotation marks, for example if I mention a black classmate or a white police officer, it is because this is the way these people have defined themselves or been defined. It does not mean that I believe these terms are helpful, accurate, or true.

I have also changed certain names and descriptive details of some characters who could not have been aware that they were interacting with a memoirist during the times that we shared.

SELF-PORTRAIT IN

BLACK AND WHITE

I N OCTOBER 2013, AFTER A LATE DINNER WITH VISITING American friends, my wifes water broke. In a daze of elation, Valentine and I did what wed planned for weeks and woke her sisters boyfriend, Steve, who gamely drove us from our apartment in the northern ninth arrondissement of Paris to the maternit, all the way on the citys southern edge. At two in the morning, we had the streets practically to ourselves, and the route Steve tookdown the hill from our apartment, beneath the greened copper and gold of the opera house, and through the splendor of the Louvres courtyard, with its pyramids of glass and meticulous gardens, over the Seine, with Notre Dame rising in the distance on one side and the Grand Palais and the Eiffel Tower shimmering on the other, and down the wide, leafy Boulevards Saint-Germain and Raspail, into Montparnasse, through that neon intersection of cafs right from the pages of A Moveable Feastwas unspeakably gorgeous. I am not permanently awake to Pariss beauty or even its strangeness, but that night, watching the city flit by my window, it did strike me that such a placeboth glorious and fundamentally not minewould be my daughters hometown.

Another twenty-four hours elapsed before Marlow arrived. When Valentine finally went into labor, even I was delirious with fatigue, sustained by raw emotion alone and thinking incoherently at best. On the fourth or fifth push, I caught a snippet of the doctors rapid-fire French: something, something, something, tte dore... It took my sluggish mind a moment to register and sort the sounds; and then it hit me that she was looking at my daughters head and reporting back that it was blond. The rest is the usual blur. I caught sight of a tray of placenta, heard a brand-new scream, and almost fainted. The nurses whisked away my child, the doctor saw to my wife, and I was left to wander the empty corridor until I found the mens room, where I shut myself and wept like all the other newborns on the floor. I mean newborn literally. Along with the litany of universal realizationsof new and daunting responsibilities, of advancing ageI was aware, too, however vaguely, that whatever personal identity I had previously inhabited, I had now crossed into something new and different. When, finally, Id washed my face and returned to meet my child, she was having amniotic fluid vacuumed out of her stomach. I sat beside my wife and helplessly watched our baby struggle into existence. Once she was calm and safe, the nurse passed her to us, and she squinted open a pair of inky-blue irises that I knew even then would lighten considerably but never turn brown. For this precious being grasping for milk and breath, I felt the first throb of what has been every minute since the sincerest love I know. And I also felt, if Im honest, something akin to the fear of death electrify me to the core. What have you done? the voice of my superego or something far stricter demanded from some distant region of my mind well beyond conscious control. What have you done! I willed it to silence. An hour or so later, when Valentine and the baby were asleep for the night, I fell back into a taxi, my own brown eyes absentmindedly retracing that beautiful and quasi-foreign route.

I HAVE SPENT my whole life earnestly believing the fundamentally American dictum that a single drop of black blood makes a person black primarily because they can never be white. I say fundamentally American, because elsewhere it is not the same. In Brazil, for example, a drop of white blood makes someone not-black. Before my daughter, Marlow, was born that night in Paris, Id never remotely questioned the idea that, when the time came to have them, my children would be black like me. They would be mixed, yes, but thats a matter of degree for all of us whose roots stretch far enough backas far as I was concerned, theyd be as black as Frederick Douglass or W. E. B. Du Bois, Lenny Kravitz or Halle Berry. Blackness as an either/or truth was so fundamental to my self-conception that Id never rigorously reflected on its foundations. My own father, whom we call Pappy in a nod to his Southern roots, is a red-brown man. Despite a dusting of freckles under the eyes and a prominent, in my mothers teasing words, Indian nose, no one has ever described him as anything other than black. His appearance, along with the strength of his persona, allowed me to assume that the Williams family identity would forever be in his image, even though my mother is unambiguously whiteblond-haired, blue-eyed, and descended on all sides from Northern European Protestant stock.