This publication is made possible in part by the Barr Ferree Foundation Fund for Publications, Princeton University

This paperback edition published by Verso 2013

First published by Verso 2011

Hal Foster 2011, 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78168-230-2

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-84467-689-7

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78168-104-6

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

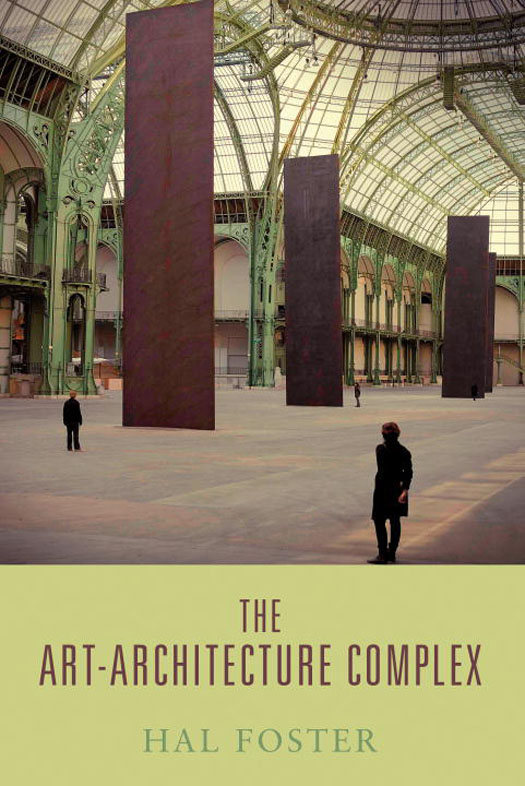

Over the last fifty years, many artists opened painting, sculpture, and film to the architectural space around them, and during the same period many architects became involved in visual art. Sometimes a collaboration, sometimes a competition, this encounter is now a primary site of image-making and space-shaping in our cultural economy. Only in part is the importance of this conjunction due to the increased prominence of art museums; it involves the identity of many other institutions, as corporations and governments turn to the art-architecture connection in order to attract business and to brand cities with arts centers, festivals, and the like. Often where art and architecture converge is also where questions about new materials, technologies, and media come into focus; this, too, makes the connection an urgent one to probe.

I begin with an overview of the role of image and surface in architecture from the moment of Pop art to the present, and conclude with a conversation with a sculptor who has long advanced a different approach to building, one that relates material to structure and body to site. A leitmotif of the book, this division has become a battle-line between practices in both art and architecture today. Within this frame are three sections of three chapters each, which explore central

The second section turns to architects for whom art was a key point of departure: Zaha Hadid, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and a group of designers informed by Minimalism, including Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. Not long ago, a near prerequisite for vanguard architecture was an engagement with theory; lately it has become an acquaintance with art. The connection is often significant, at least in a strategic way: Hadid launched her career with a return to Russian Suprematism and Constructivism, and Diller Scofidio + Renfro began their practice with a fusion of architecture with Conceptual, performance, feminist, and appropriation art. With designers influenced by Minimalism, the reciprocity of art and architecture is no less fundamental; just as Minimalists opened the art object to its architectural condition, so have these architects acquired a Minimalist sensitivity to surface and shape. As might be expected, recent developments in museum design come to the fore in this section.

All these involvements have altered not only the relationship between art and architecture, but also the character of such mediums as painting, sculpture, and film. The third section considers these transformations. Sculpture is what you back into when you back up to see a painting,

What relation do contemporary art and architecture have to a greater culture that prizes experiential intensity? Do their own intensities counter this larger one? Sublimate it? Cover for it somehow? Such questions also recur in what follows.

New materials and techniques play a role in contemporary design that is aesthetic as well as functional. Like the International Style, the global styles of Rogers, Foster, Piano, and others often feature heroic engineering, and once again technology is seen as a virtue, a power, in its own right, as though it were a fetish to ward away the unsavory aspects of the very modernity of which it is a part. (This new Prometheanism was bucked up, not knocked back, by the attacks of September 11: tall buildings in iconic shapes were thought to inspire moral uplift, not to mention financial interest and political support. Who can forget the phallic cry of Build them higher than before!?) Contemporary materials and techniques tend to be light, and this lightness, another leitmotif of this book, has affected art as well as architecture. In particular it has forced a revaluation of the old values of material integrity and structural transparency, the vicissitudes of which I also consider here. An essential ideologeme of modernity today, lightness has supported an abstraction beyond any seen in modernismone said to be in tune with the abstraction of cybernetic spaces and financial systems. Yet this lightness comes with a conundrum of its own, for how is modernity to be represented thereby? If the machine age had its distinctive iconography, what is ours?

Even as Herzog and de Meuron used as the default logo of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.)

Imageability, then, is another theme of this book (especially in the second section), and here the architecture-art connection is explicit. One positive development is that some work is able to carve out spaces, within conditions of spectacle, for experiences that are not scripted or even expected. Another is that some work is able to site its structures in ways that resist any easy consumption as image-events. Imageability remains a tricky business, though, especially when it comes to recent designs of art museums. Some of these buildings are so performative or sculptural that artists might feel late to the party, collaborators after the fact. Others make such a strong claim on our visual interest that they might compete in a register that artists like to claim as their ownthe visual. Architects have every right to operate in these arenas, of course, but sometimes in doing so they might neglect other matters (program, function, structure, space) that they address more effectively than artists. These confusions, too, are considered in what follows.

Lest I jump my own gun, let me mention just one more concern (especially in the third section): the question of artistic medium. Debate on this subject long stalled over the opposition between a modernist ideal of specificity and a postmodernist strategy of hybridity, yet these positions mirrored each other, as both sides assumed that mediums have fixed natures, with artists encouraged either to disclose them or to disturb them somehow. My understanding diverges from such accounts. In the first instance, mediums are social conventions-cum-contracts with technical substrates; they are defined and redefined, within works of art, in a differential process of both analogy with other mediums and distinction from thema process that occurs in a cultural field that, vectored by economic and political forces, is also subject to continual redefinition.McCall seeks to be autonomous, yet it implicates drawing, photography, sculpture, and architecture in that search. This question of medium is not an academic one, for an important struggle is waged between practices like these concerned with embodiment and emplacement and a spectacle culture that aims to dissolve all such awareness. The dialectic of postwar art, I suggest here, has produced not only a move from pictorial illusion into actual space, but also a refashioning of space