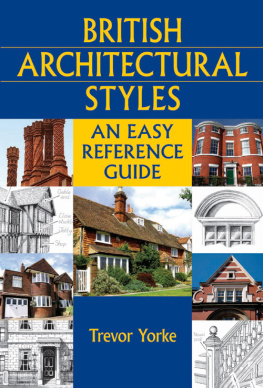

BRITISH

ARCHITECTURAL

STYLES

Trevor Yorke

COUNTRYSIDE BOOKS

NEWBURY BERKSHIRE

First published 2008

Trevor Yorke, 2008

All rights reserved. No reproduction permitted without the prior permission of the publisher:

COUNTRYSIDE BOOKS

3 Catherine Road

Newbury, Berkshire

To view our complete range of books, please visit us at www.countrysidebooks.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 84674 082 4

Designed by Peter Davies, Nautilus Design

Produced through MRM Associates Ltd., Reading Printed by Cambridge University Press

All material for the manufacture of this book was sourced from sustainable forests

Introduction

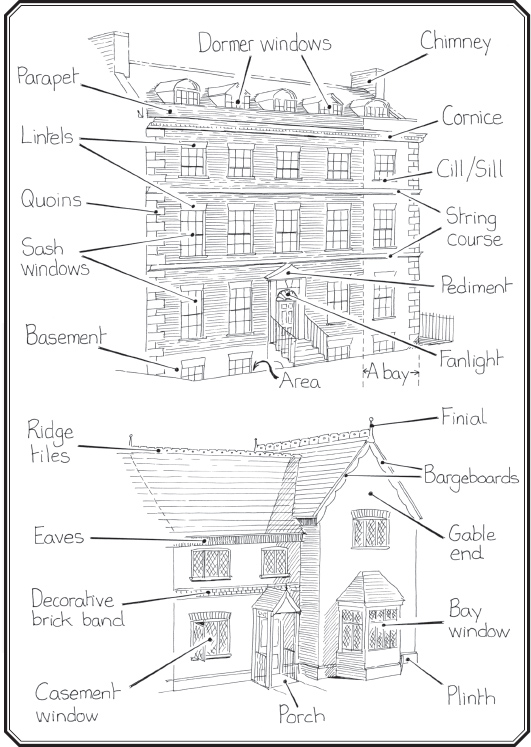

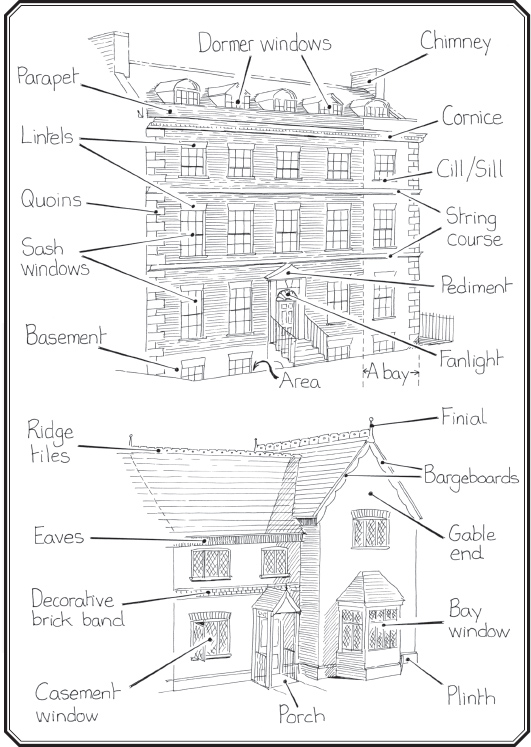

H ouses are more than homes. They can be outward expressions of the owners aspirations, a reflection of the local geology, or a canvas for the latest fashion to appear on. En masse they can form imposing terraces and squares which characterise a town. Medieval York, Georgian Bath, Regency Brighton and Victorian Manchester are just some of the places distinguished by their housing. Yet, where do you start if you wish to understand the immense and bewildering range of structures and styles? This book simply uses drawings to illustrate the principal changes through the ages which can help you date and appreciate houses. At the end is a glossary, timechart and a list of other books in this range should you wish to take the subject further.

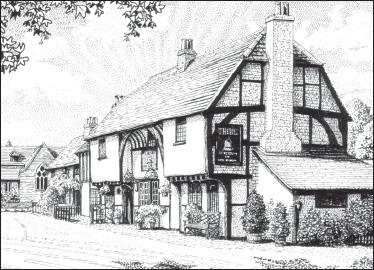

There are a few general points which are worth mentioning before looking in detail at period houses. The 450 years or so covered in this book have seen immense changes in bricks and mortar. When Henry Tudor became King of England in 1485 most of the few million population still lived off the land, in homes which were only designed to stand for a generation or two. The houses which generally survive today from then and up to the 18th century are the finer quality urban and country houses, most of which were vernacular, made from local materials by masons and carpenters who passed their knowledge down from one generation to the next. There were, however, underlying structural and decorative changes which are common across most of the country rather than just one region and the early chapters focus upon these.

In this pre industrial age, fashion took time to spread, so a new style in London may not appear in the far flung reaches of the country until fifty years later. Few also could afford to completely replace their house, so the latest fashion was applied over an older structure. Dates on the outside, especially of 18th-century buildings, are often of the refit and not the original structure beneath. Interiors change regularly and few original ones survive, but more permanent fixtures like stairs and fireplaces can be found so it is these which are generally shown at the end of each chapter.

Housing makes dramatic changes from the 18th century as tighter regulations, improved transporting of goods and ideas, increased wealth and a booming population resulted in standardisation of form, widespread availability of materials, and national styles. Vernacular housing is replaced by uniform brick and stone structures, with the latest decoration applied to its exterior. A wider range of houses survives from this period, including smaller terraces built for an emerging middle class, and the illustrations in the later chapters reflect this broader diversity of building.

Chapter

Tudor House Style

1485 - 1560

Hampton Court, Surrey:This most notable of Tudor houses was built by Cardinal Wolsey but fell into Henry VIIIs hands, who set about expanding it into a royal palace. This gatehouse incorporates all the fashionable features of the day, including red brick with stone dressing, diaper patterns, oriel windows and prominent chimneys, yet still retains medieval details like the crenellations along the top and the courtyard layout.

T he Tudor period was one of great change, improving fortunes and notorious monarchs! The feudal system, cornerstone of medieval society, had broken down as a population, halved by the Black Death and subsequent periodic outbreaks of plague, sought greater freedom and opportunities, with families originally from a poor background acquiring land and wealth over generations to become yeomen farmers, merchants, or even gentry. The creation of the Church of England and the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII created huge social upheaval and resulted in a large amount of land being granted to the Kings favourites, although doubts over the permanence of his actions meant few did much with their new properties in this period. It is the houses, large and small, of these newly successful families, alongside those of the existing landed classes, which survive today.

Structure

Tudor towns and cities were generally small, with houses set upon thin plots of land with a narrow frontage overlooking the street. Villages were dominated by the manor house and two-storey farmhouses while around them the majority of the rural population was housed in simple buildings of timber, mud or rubble. These were often shared with the livestock and may have lasted a few hundred years or just a generation, but only survive today as raised platforms in deserted villages. The houses of the successful and wealthy were generally one room deep because the weight of the roof structure limited greater width, and there was little attention to outward display and style. Most large houses were asymmetrical arrangements of buildings looking inwards upon a courtyard. The urban houses of merchants and tradesmen often had a shop, warehouse or workshop on the lower storey with accommodation jettied above.

Wealden House:A popular style of house in the south and east of the country was the Wealden House. Built for the lesser gentry and farmers, it had a recessed open hall in the centre with two-storey cross wings at either end, all under a single roof.

Exterior Style

The gentry had been little concerned with the arts, their wealth was spent embellishing the House of God to secure passage through purgatory rather than in decorating their own residences. It was later in this period before they became aware of the artistic flowering of the Renaissance, only for contact with this new flow of European culture to be severed by the Reformation. The finest timber-framed houses featured close studding (tightly fitted vertical members) or had decorative timber patterns set in the panels to demonstrate the owners wealth. Many, especially in towns, had jetties overhanging the lower floor, a status symbol as much as a way of creating extra space. Bricks were typically red, often with stone dressing for the windows and quoins (corner stones) and diaper patterns (diagonal crosses) formed out of over-burnt dark grey bricks.