THE VICTORIAN PUMPING STATION

S team-powered pumping stations with their rich decorative architecture and mighty beam engines are amongst the most distinctive and important buildings of the nineteenth century. They were built to drain agricultural land and improve production, top up the water in canals to keep commercial traffic moving, and supply the hydraulic systems that powered industrial machinery. The most impressive, however, were erected as part of revolutionary, large-scale water supply and sewerage disposal systems, which significantly improved the health of the nation. Before looking in detail at these intriguing buildings we will briefly explain why these ornate municipal pumping stations came into being in the first place.

The population of industrial towns and cities was booming in the early nineteenth century. In the first three decades Liverpool grew from 82,000 to 202,000, Leeds from 53,000 to 123,000 and London from around 1,000,000 to 1,730,000 inhabitants. Most of them were squeezed into accommodation without clean running water and effective methods of waste disposal. The situation was made even worse because many who moved from the country brought their livestock with them. Inevitably, disease became rampant in working-class areas as the continued demand for housing overwhelmed the existing utilities and created the notorious Victorian slums.

The Victorians love of decorative forms extended to the interior of many pumping stations, as in the ornate cast-iron structure of the central octagonal well at Crossness Pumping Station in South East London.

The initial lack of action in dealing with these problems was partly due to the ethos of self help, which resulted in the authorities resisting calls for action. They were content to let local corporate initiative take the lead and were reluctant to pass legislation unless the situation became so chaotic that it would restrict enterprise. Improvements to water supply and sewerage were also hindered by peoples misunderstanding of the ways in which disease could be spread; until the second half of the nineteenth century most people believed in the miasma theory the idea that deadly outbreaks were caused by poisonous particles of decaying matter in foul-smelling air. The word malaria is derived from the Italian words malaand aria(bad air), since this was believed to be the source of the disease. The fact that unpleasant odours seemed to hang over the slum areas where epidemics were centred only added weight to the theory.

One of the first to disprove this idea was Dr John Snow. Whilst working in London during the cholera epidemic of 1849 he studied an outbreak in the south of the city and realised that the water supply was being contaminated by cesspits in the rear of the properties during heavy rainfall, and that the disease broke out shortly afterwards. He made a similar study in 1854 in Soho, plotting the occurrences of the disease and tracing it back to a water pump in Broad Street (now Broadwick Street). Once he had the handle removed the number of cholera cases quickly subsided. Although his theory that the disease was water-bound would not be proven until the 1880s, his voice was one amongst a growing number calling for action to improve the quality of drinking water and create an effective sewerage system.

Great pride was taken in the huge steam-powered beam engines that operated the pumps. This beautifully maintained example at Papplewick Pumping Station formerly supplied water to Nottingham.

Mounting pressure upon the government came not just from these vocal campaigners: there were by now hard facts and detailed reports that would force their hand. The census, first carried out in 1801 and by 1841 recording full details about individuals and their occupations, clearly illustrated the population shift and where it was most dense; photographs recorded the slum conditions in which many were living. An increasing number of Royal Commissions were set up, which could be shocking in their detail and led to undeniable conclusions. A new official, the inspector, became key in highlighting the plight of the working classes at a local level. One such man, Robert Rawlinson, was sent to look into the sanitary conditions in Sunderland in 1850 and published a report in the following year which opened the eyes of those in authority to the shocking state of poor housing in the area. He described a cottage whose walls were constantly wet and which stood next to large mounds of manure and recalled, When I first visited this cottage I found it occupied by a very clean old woman and her husband; their bedroom was very offensive; they are both since dead of cholera.

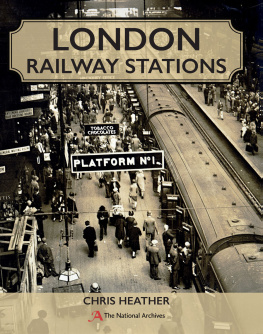

One of the earliest uses of steam-powered pumps was to top up the summit level of canals. The original 200-year-old Boulton and Watt steam engine at Crofton Pumping Station, Wiltshire, still supplies water to the Kennet and Avon Canal.

As a result of this growing weight of information, local and national government passed legislation that would ultimately result in the authorities taking responsibility for public utilities. The 1835 Municipal Corporation Act reformed over 170 boroughs across the country (excluding London, which had its own reforms) and established town councils elected by ratepayers. The 1848 Public Health Act enabled those boroughs that had formed a corporation to take responsibility for water supply and sewerage removal.