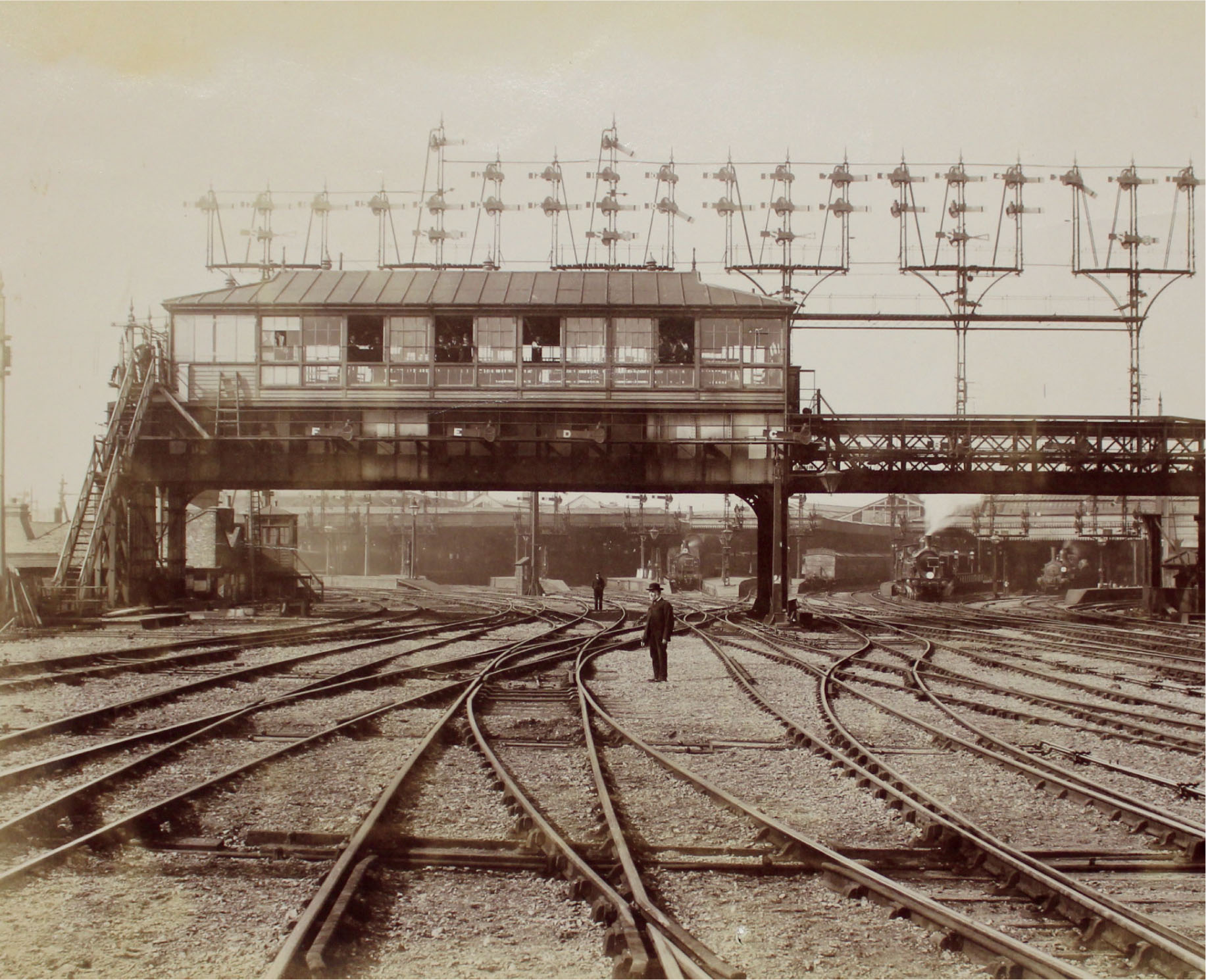

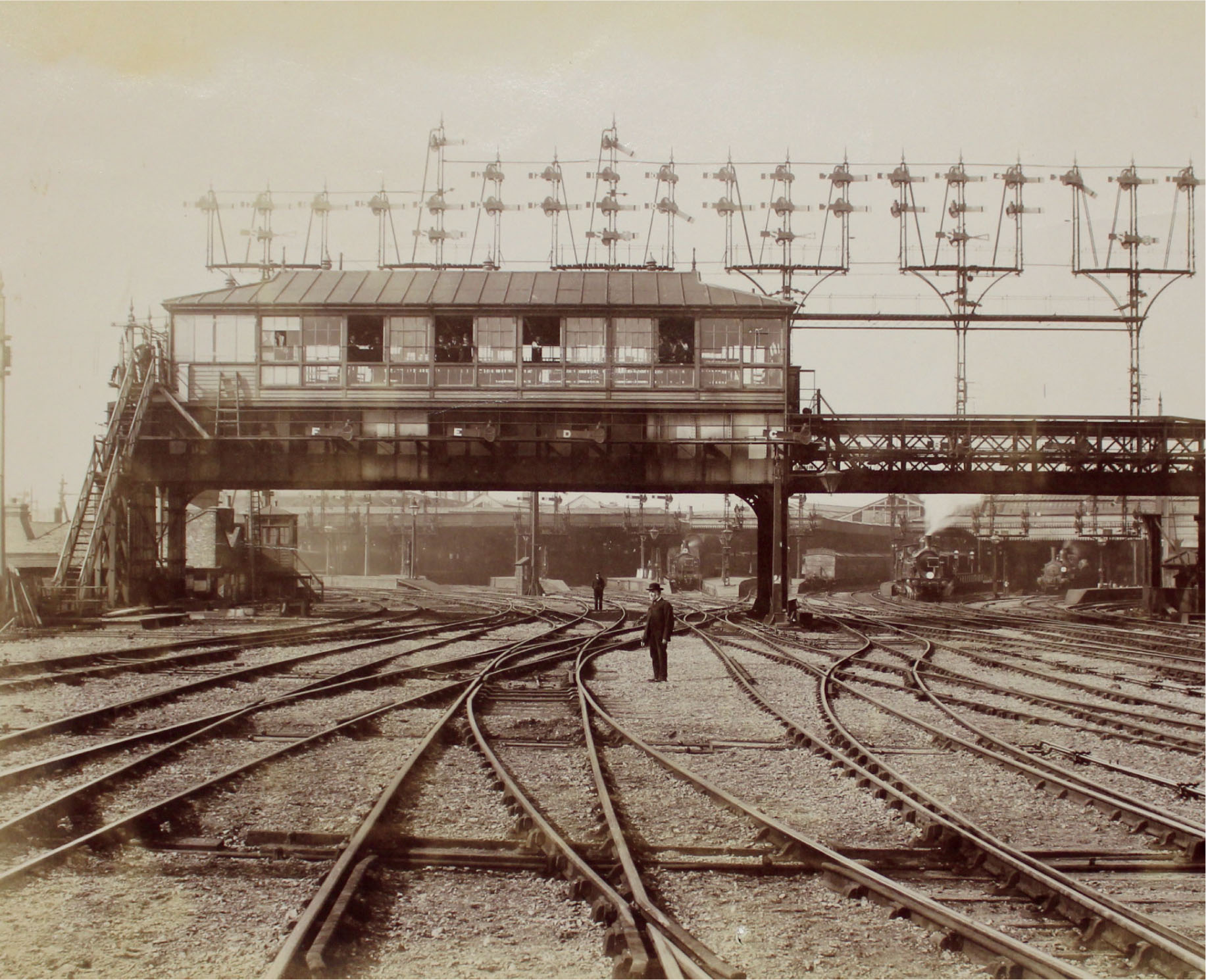

Waterloo Station Junction COPY1409/219

First published in 2018 by

Chris Heather, an imprint of

The Crowood Press Ltd,

Ramsbury, Marlborough,

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

Crown Copyright

Images reproduced by permission of The National Archives, London

England 2018

The National Archives logo device is a trade mark of The National Archives

and is used under licence.

The National Archives logo Crown Copyright 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 2765 5

Disclaimer

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace and credit illustration copyright holders. If you own the copyright to an image appearing in this book and have not been credited, please contact the publisher, who will be pleased to add a credit in any future edition.

Contents

Introduction

W HEN THE RAILWAYS BEGAN TO BE built in Britain over 180 years ago, London was already the largest city in the world. With a population of around two million people in 1830, London was not only a capital city: it was the hub of the British Empire, soon to become the largest empire the world had ever seen. No wonder, then, that London became a magnet for business, trade, work and entrepreneurs. A key aspect to this development was the coming of the railway, a transport system that changed the face of London forever.

Nearly three billion rail journeys are undertaken each year in the UK, and nine of the ten busiest stations are in London. Waterloo Station alone deals with a quarter of a million passengers each day. There are thirteen mainline termini in London, more than in any other capital city. Moscow, for example, has only nine mainline stations, while the French capital, Paris, a city of similar age and status to London, has a mere seven. There are two main reasons why London has so many stations: firstly, Britain was the first country to develop a railway system at a time of huge industrialization, when goods and people needed to move around the country, and businessmen saw opportunities to make large profits. London was therefore ahead of the game.

Secondly, the British Government saw no need to provide an overall plan for the railway network across the country, or in the capital. It was left to individual companies to propose new railway lines, seek parliamentary approval, and raise enough capital to get started. This led to huge competition and rivalry between the various railway companies, each one striving to make money by choosing a different market, whether it was holiday traffic to Devon, the movement of beer from Burton-on-Trent, daily commuters to London, or collecting goods arriving at the Thames docks. This freedom was fertile ground for engineers and architects to come up with unique buildings and structures, many of which can still be seen today.

The laissez-faire approach to transport infrastructure also led to the duplication of lines, the unnecessary embellishment of buildings, the demolition of housing, vast over-expenditure by companies, and many other issues, which can be seen as good or bad depending on ones perspective. Nevertheless, this is how the railways evolved, and how they came to influence the layout of the capital city we know today.

The story of Londons stations is one of co-operation and competition, personal ambition and corporate determination. It includes instances of innovative design, technological invention, devotion to service, and triumph over bureaucracy and difficult physical terrain. All thirteen mainline stations were built during a sixty-four-year period, starting with London Bridge Station, which opened in 1836, and ending with Marylebone, which was the last to open in 1899. Each one has its own personality and its own charms and idiosyncrasies. These were determined by location, the functions the stations were designed to perform, the status of the architect, the pride of the railway company, and of course the amount of money available at the time.

These buildings were new inventions in themselves. No one had created a large railway terminus in a capital city before, and nobody knew how they should look or what they should include, and although mistakes were sometimes made, architects had a free rein to create buildings that would be both functional and impressive. Often they would borrow from the grand styles of classical Greek, Roman and Gothic architecture, and this theme would be extended to the associated railway hotel, many of which are today some of the most richly decorated and luxurious hotels in London. As well as hotels, each station could have a retinue of support buildings: offices, stables, goods yards, signal boxes, bridges, viaducts and railway lines, which provided succour to new urban development along their routes, with housing and businesses contributing to the suburbia that would eventually become Greater London.

This book tells the story of each of these stations, how they came to be positioned where they are, who designed them, and what happened to them over time. Through these pages we meet some of the people who built them, worked in them, passed through them as travellers, and even died in them. A wide variety of human activity can be seen here, each anecdote contributing to the narrative of these vital structures that are so familiar to us, and yet which come from another age an age of steam, smoke, gas lamps and horses. This was an age when a rented brass foot warmer was the height of luxury, and when hailing a cab from the station meant travelling by two wheels and four hooves.

These stations have survived many changes over the years, some more sympathetic than others, but most of them include preserved examples of their original design, bearing testament to the perception, skill, enthusiasm and foresightedness of their Victorian creators. I would encourage you to visit them, to take in the atmosphere and to spot some of the original features, since all can be reached in a couple of hours quite easily from the Circle Line on the Underground. And I hope this book will bring new light to what may be for you very familiar buildings, and help you to see Londons mainline stations through new eyes.

Chris Heather, 2018

Chapter 1

LONDON BRIDGE, 1836

T HE STORY OF LONDON BRIDGE STATION begins with Lieutenant-Colonel George Thomas Landmann, your archetypal Victorian adventurer. A man with an entrepreneurial spirit, he played his part in literally building parts of the British Empire. The son of a German professor, he was born in the grounds of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, in 1780. He lived a full and varied life, and his colourful escapades, and his inventiveness and ability to get things done, helped to change the face of London.

Next page