THE GROUPING

A t the end of the First World War, Britains railways were in a parlous state. Years of heavy use and inadequate maintenance had taken a toll on a network that had been built by over a hundred private companies that ranged in size from the major players such as the Great Western, the Midland and the London and North Western to minor lines serving essentially local needs. Many of these companies were in financial difficulties, with a total deficit of over 40 million, partly because of the impact of the war, and partly because of the considerable duplication of routes and stations, the result of fierce competition between Victorian railway builders. During the war, the government had taken control of the railways, while stopping short of actual nationalisation, and this control continued into the immediate post-war years.

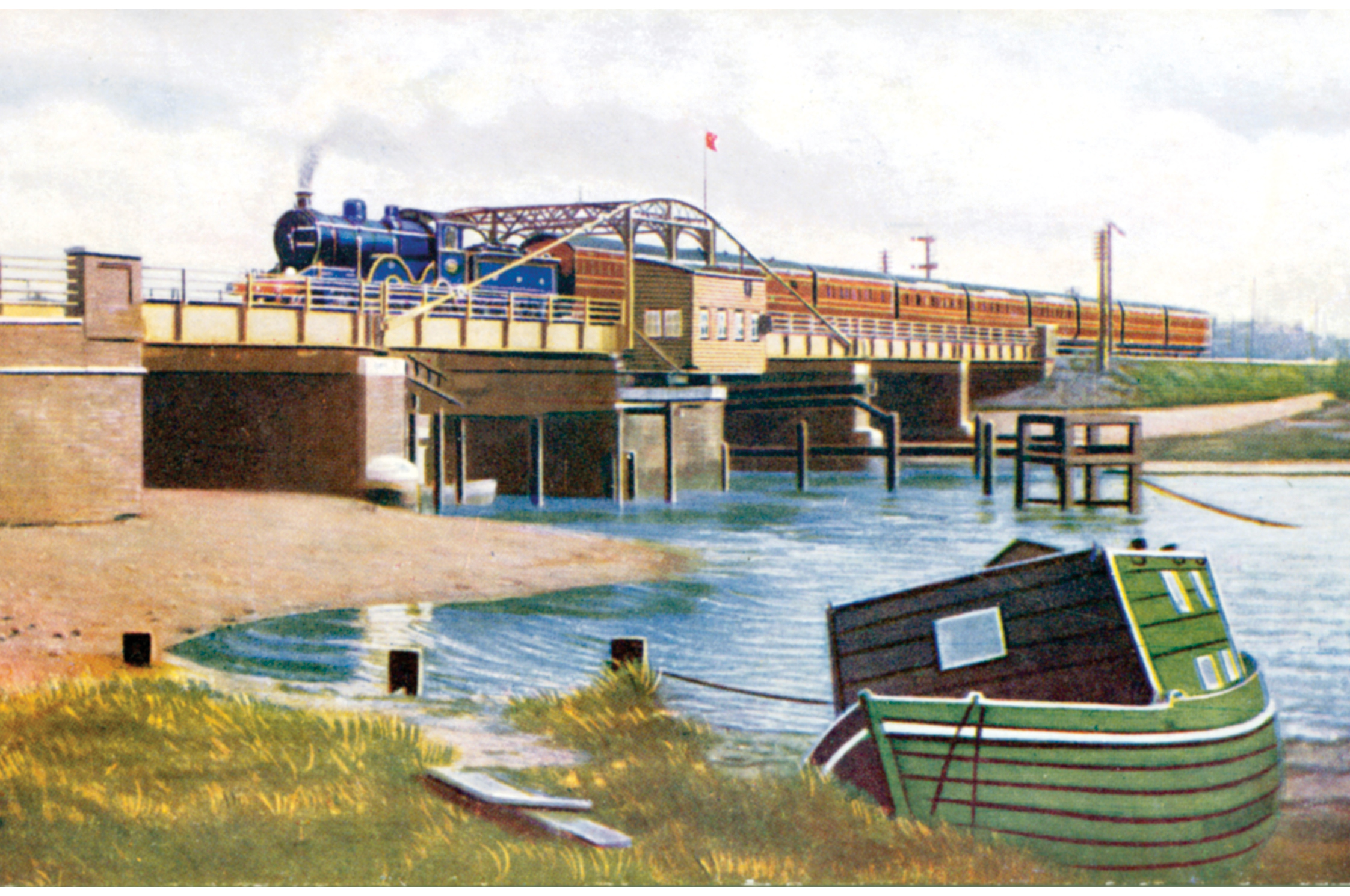

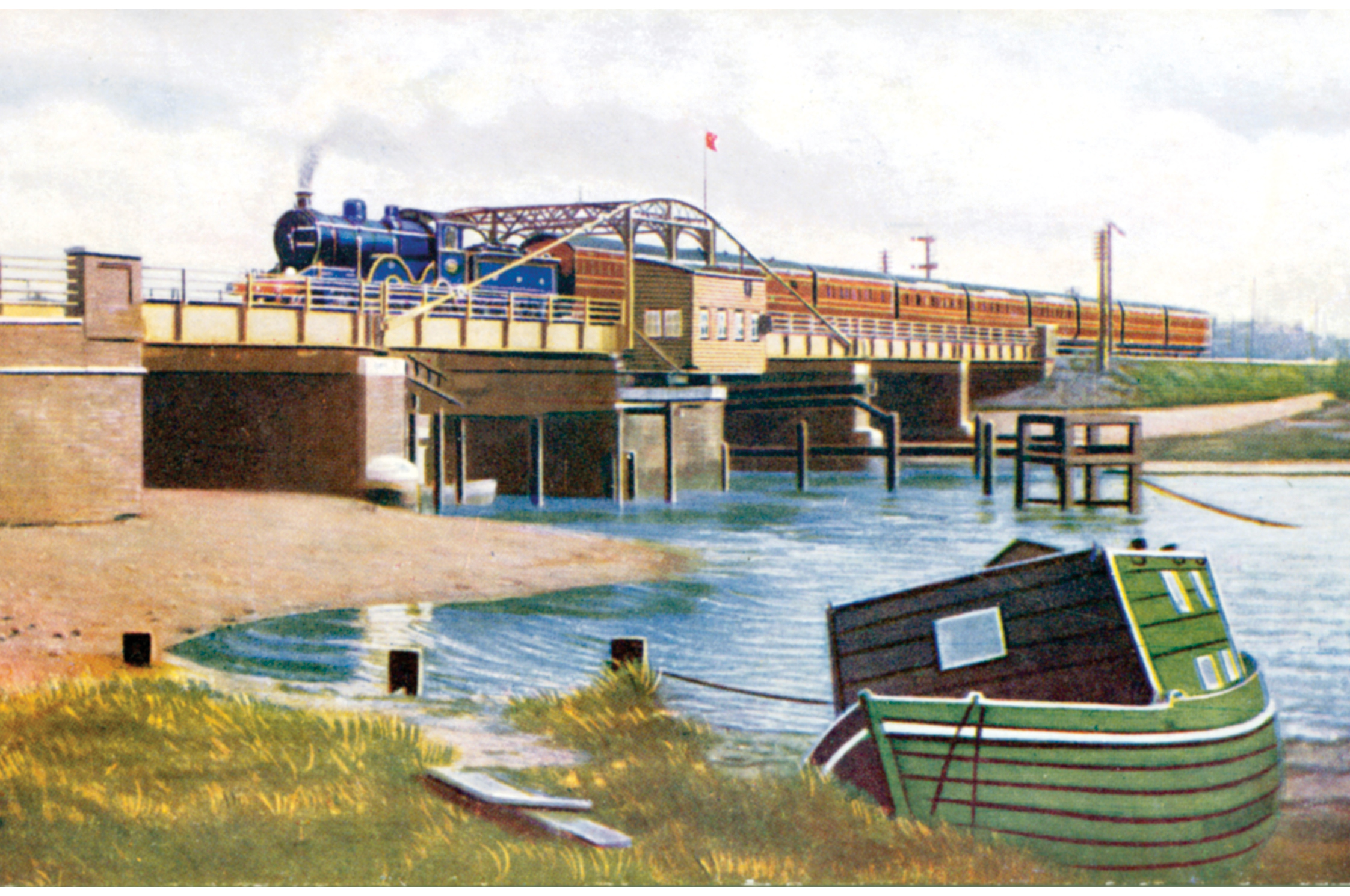

Postcard depicting Great Eastern Railway 4-4-0 Class T19 locomotive and passenger train crossing Trowse swing bridge near Norwich, in about 1910.

In 1920 Eric Geddes, the Minister of Transport and a former deputy general manager of the North Eastern Railway and First Lord of the Admiralty, was asked to put together a plan for the future of Britains railways. His White Paper formed the basis of the Railways Act of 1921, known popularly as the Grouping Act, the essence of which was that the major railways should be brought together into large regional groups. The original proposal was for six or seven areas or groups, including a separate one for Scotland, but for the Act that was passed in August 1921 this was reduced to four with Scotland included, defined as the Great Western Railway (GWR), the Southern Railway (SR), the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) and the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). These quickly became known as the Big Four. A subsequent Act in 1933 created the London Passenger Transport Board to operate the capitals transport network. Though the regional boundaries were clearly drawn, there was inevitably some overlap and some anomalies, usually the result of pre-Grouping partnerships. Obvious examples were the LNERs operation of the West Highland line to Mallaig, deep into LMS territory, and the LMSs control of the former London, Tilbury and Southend route eastwards from London into LNER territory. However, the core separation was between the main routes from London to Scotland, with the LMS having the West Coast route, and the LNER the East. The Railways Act came into force on 1 January 1923.

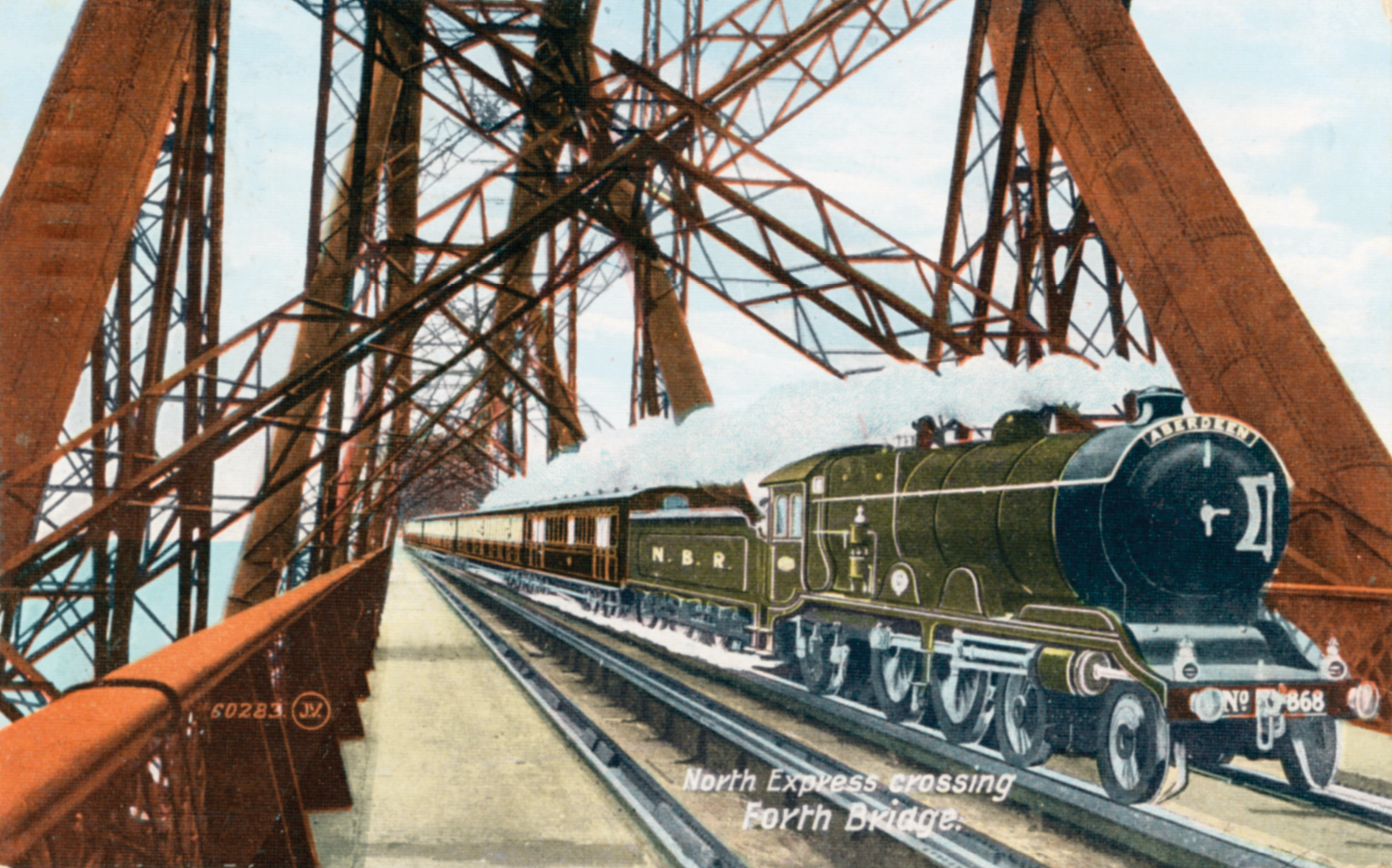

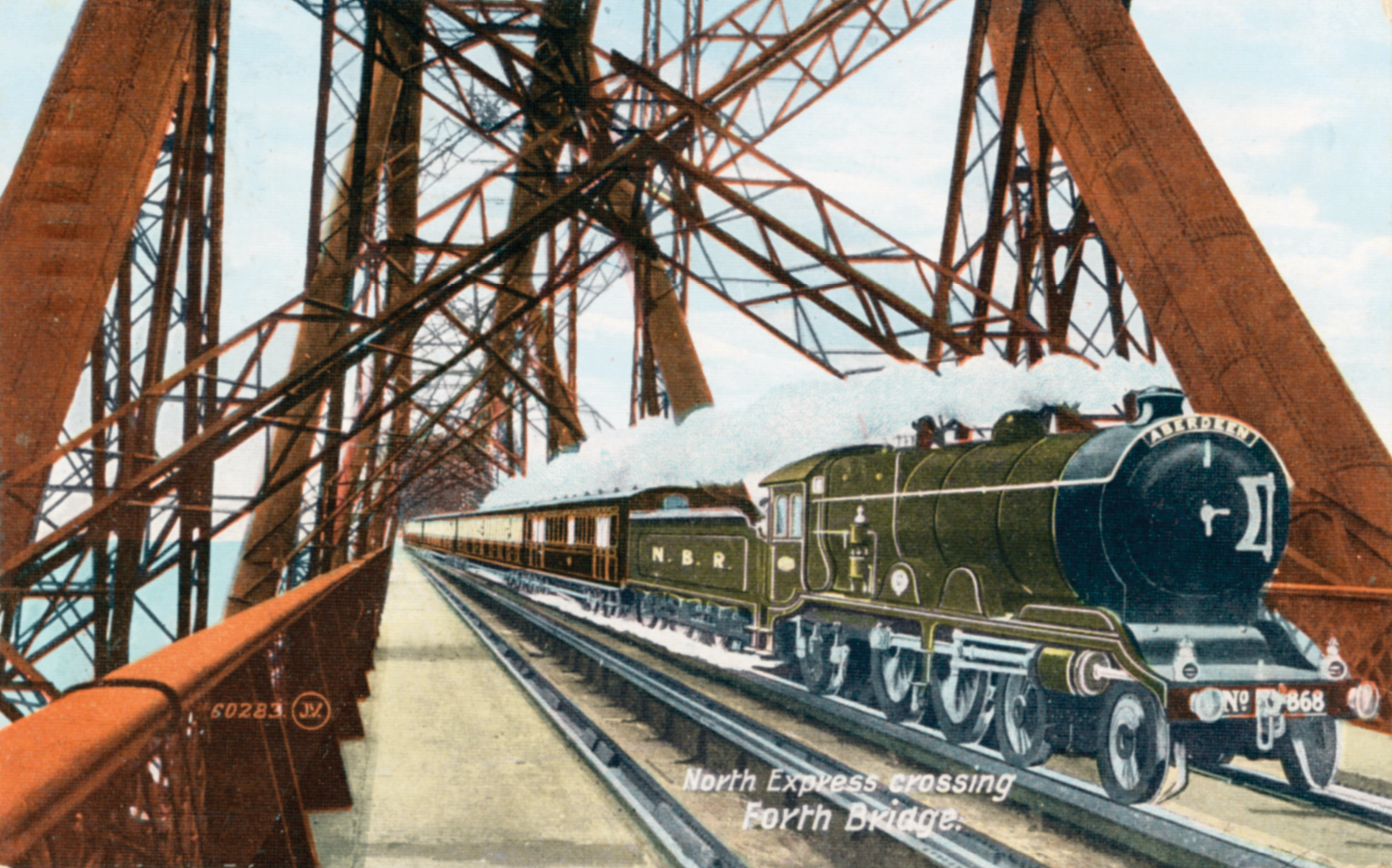

Postcard depicting North British Railway 4-4-2 Class H locomotive crossing the Forth Bridge in about 1910.

The main constituent companies of the LNER were the Great Eastern Railway, the Great Central Railway, the North Eastern Railway, the Great Northern Railway, the Hull and Barnsley Railway, the North British Railway and the Great North of Scotland Railway. The most important of these, the GER, the GCR, the NER and the GNR, had themselves been created by mergers and amalgamations during the previous century, while the ambitious NBR was the largest railway in Scotland. In addition, brought into the Group were many other lesser lines, giving the LNER a route length of 6,590 miles and making it the second-largest of the Big Four. The very long list of subsidiary, leased and jointly operated lines included a few independent companies, such as the Mid-Suffolk Light Railway, and a large number of lines leased or worked by the main constituent LNER railways. There were about twenty-four of these, mostly either short connecting railways or nominally independent local and branch lines. They ranged from minor or obscure companies, such as the NERs goods only Fawcett Depot Line, the GCRs North Lindsey Light Railway, the GNRs Stamford and Essendine Railway and the NBRs Lauder Light Railway, to substantial and sometimes important lines on the railway map, such as the GERs London and Blackwell Railway, the GNRs East Lincolnshire Railway, the NBRs Forth and Clyde Junction Railway and the Hull and Barnsleys South Yorkshire Junction Railway.

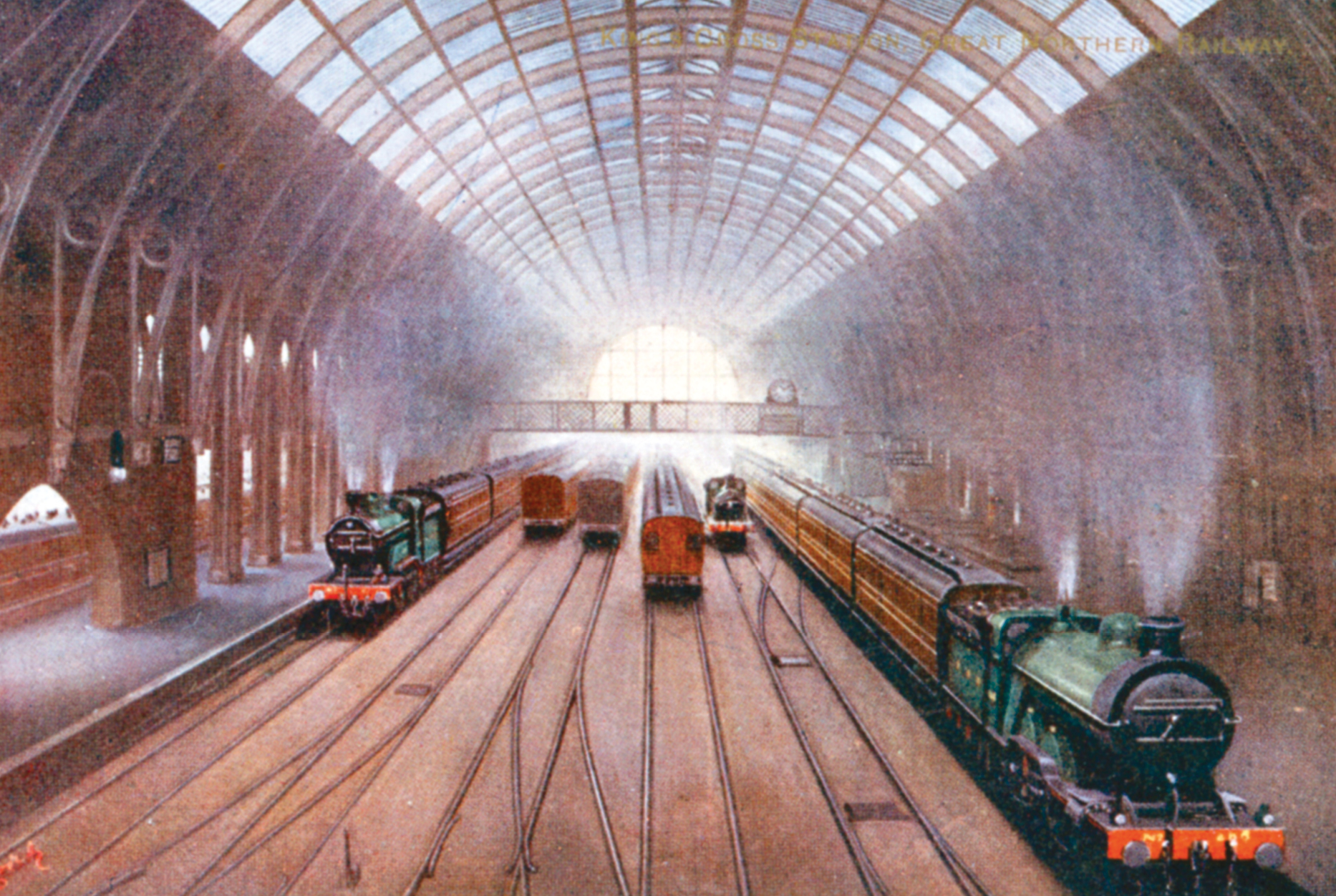

Postcard depicting Great Central Railway 4-4-0 Class 11B locomotive heading a Sheffield and Manchester express from Marylebone station in about 1912.

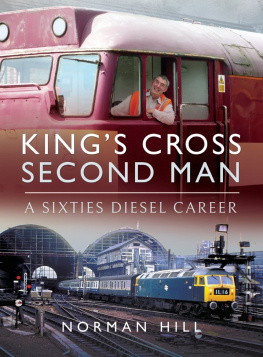

There were also over twenty jointly operated lines, mostly shared with the LMS. The largest of these were the 183-mile East Anglian network of the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway which, though incorporated into the LNER in 1936, continued to be shared by the LNER and the LMS, and the 142-mile Cheshire Lines Committee. Other joint LNER and LMS lines were to be found in many parts of England and Scotland and included the Axholme Light Railway, the Dundee and Arbroath Railway, the Great Central and North Staffordshire Joint Railway, the Norfolk and Suffolk Joint Railway and the Tottenham and Hampstead Junction Railway. The LNERs route map ran from London to Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Elgin and included Leicester, Sheffield, Manchester and Carlisle, along with most of East Anglia and all of eastern England from the Thames to Newcastle and the Border. In London, the LNERs main termini were Kings Cross, formerly GNR, Liverpool Street, formerly GER, Marylebone, formerly GCR and Fenchurch Street, formerly London and Blackwall Railway.

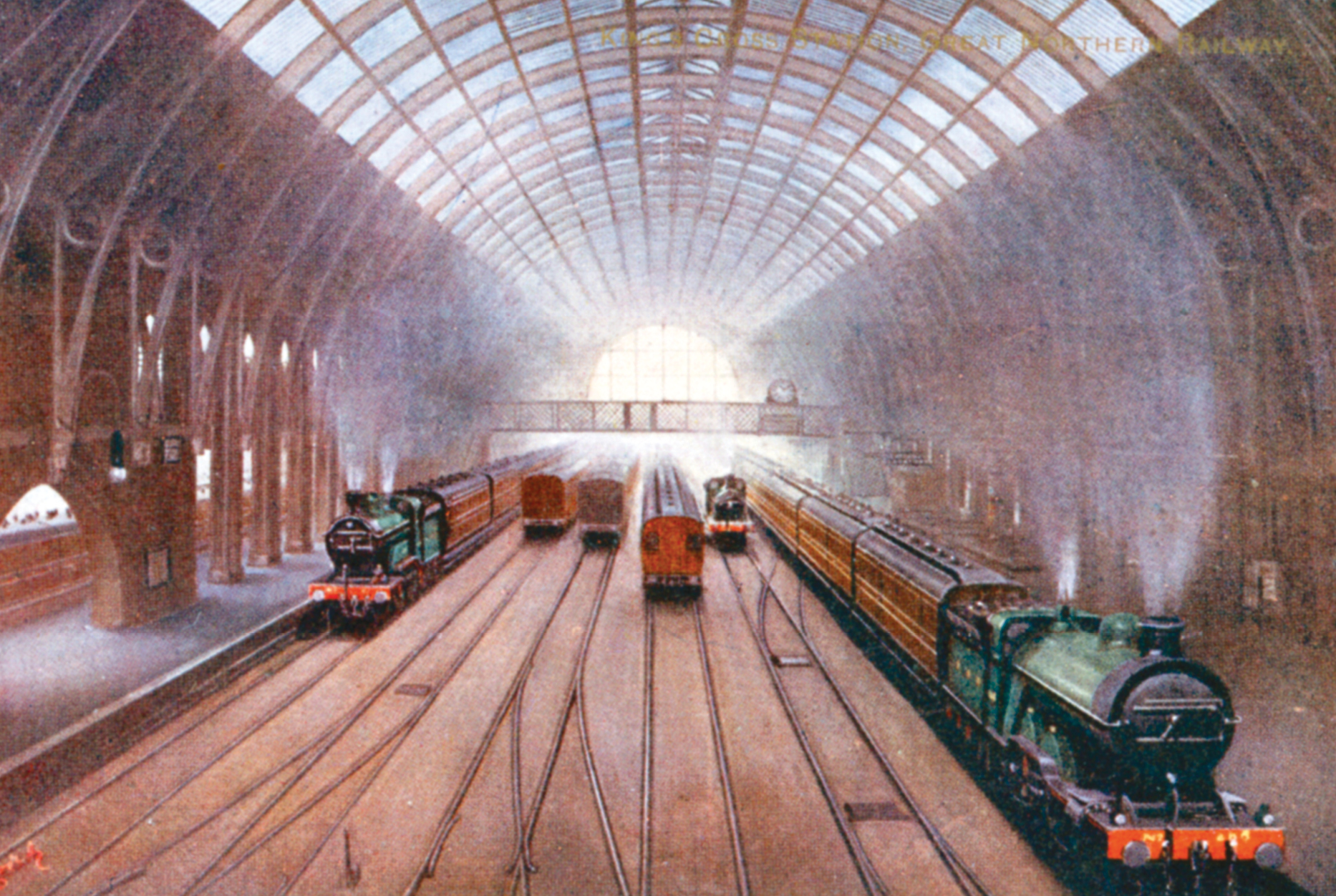

Postcard depicting Kings Cross Station during the Great Northern Railway era, in about 1910.

SETTING UP THE BUSINESS

A t its formation the LNER found that it had inherited over 7,000 steam locomotives, 20,000 carriages, around 30,000 freight vehicles, a small fleet of electric trains and steam and motor railcars, over forty passenger and freight ships, a number of river and lake steamers, over twenty hotels and a massive fleet of road vehicles, including 800 mechanical horse tractors. It had shares in bus and road transport companies, and there were over 2,500 stations and goods depots, along with thousands of other buildings, including warehouses, signal boxes, houses and cottages, engine sheds, workshops and offices. The LNER also took charge of docks and harbours in twenty places, the most important of which were Hull, Immingham, Harwich, Grimsby, Hartlepool and London, along with Leith and Aberdeen. There were also smaller wharves and piers all over the network and eight canals. Over 205,000 staff were employed, along with a large number of horses.

From the start, the LNER built a reputation for sound and careful but creative management. The chairman, William Whitelaw, came from the NBR and the deputy chairman, Lord Faringdon, came from the GCR, companies well known for their careful and thrifty behaviour. The chief general manager, Sir Ralph Wedgwood, and his assistant, Robert Bell, both came from the NER.

The main challenge facing the LNER was the integration into one company of many independent railways, large and small. Many were well known as efficient and well-run companies that had been financially viable until the depredations of the First World War, and they were generally regarded with great loyalty by both staff and customers. The larger ones had successfully operated a great range of trains over a long period, which included main-line and secondary passenger traffic, commuter services, excursions and a significant freight business. In addition some ran a network of dining and sleeping cars, along with steamers and hotels. Some, such as the GNR, were already famous for the quality and originality of their publicity and had established a particular look, or image. The larger companies had also built their own locomotives and vehicles, often with distinctive and individual approaches to design, construction and operation.