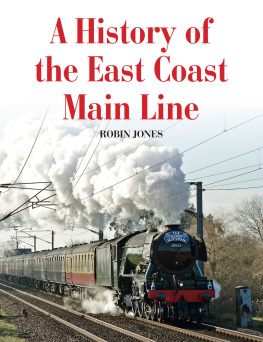

A History of

the East Coast

Main Line

A History of

the East Coast

Main Line

ROBIN JONES

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2017 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2017

Robin Jones 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 287 8

Frontispiece: The greatest racehorses of the East Coast Main Line: the last line-up of all six surviving Gresley A4 streamlined Pacifics, including the pair repatriated temporarily from North American museums, took place at the Locomotion Museum in Shildon, County Durham, in February 2014. Pictured left to right on the evening of 19 February are Nos 60007 Sir Nigel Gresley, 60008 Dwight D. Eisenhower, 60009 Union of South Africa, 4489 Dominion of Canada, 4464 Bittern and 4468 Mallard, the world steam railway locomotive speed record holder. (Fred Kerr)

Title page: On 30 September 2015, in the waiting room on Platform 2 at Grantham, the official unveiling took place of the spectacular stained-glass window depicting world steam railway speed record holder Mallard, created by local artist Mike Brown. (Author)

Dedication

To Vicky and Ross, who both began their careers travelling on the East Coast Main Line.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Brian Sharpe, Dennis Butler and the A1 Steam Locomotive Trust.

All pictures credited CCL are published under a Creative Commons licence. Full details may be obtained at http://creativecommons.org/licenses.

Pictures credited AUTHOR were taken by the author. Pictures credited AUTHORS COLLECTION are non-copyright pictures from the authors personal collection.

All pictures taken inside the National Railway Museum were taken with the permission of the NRM.

Contents

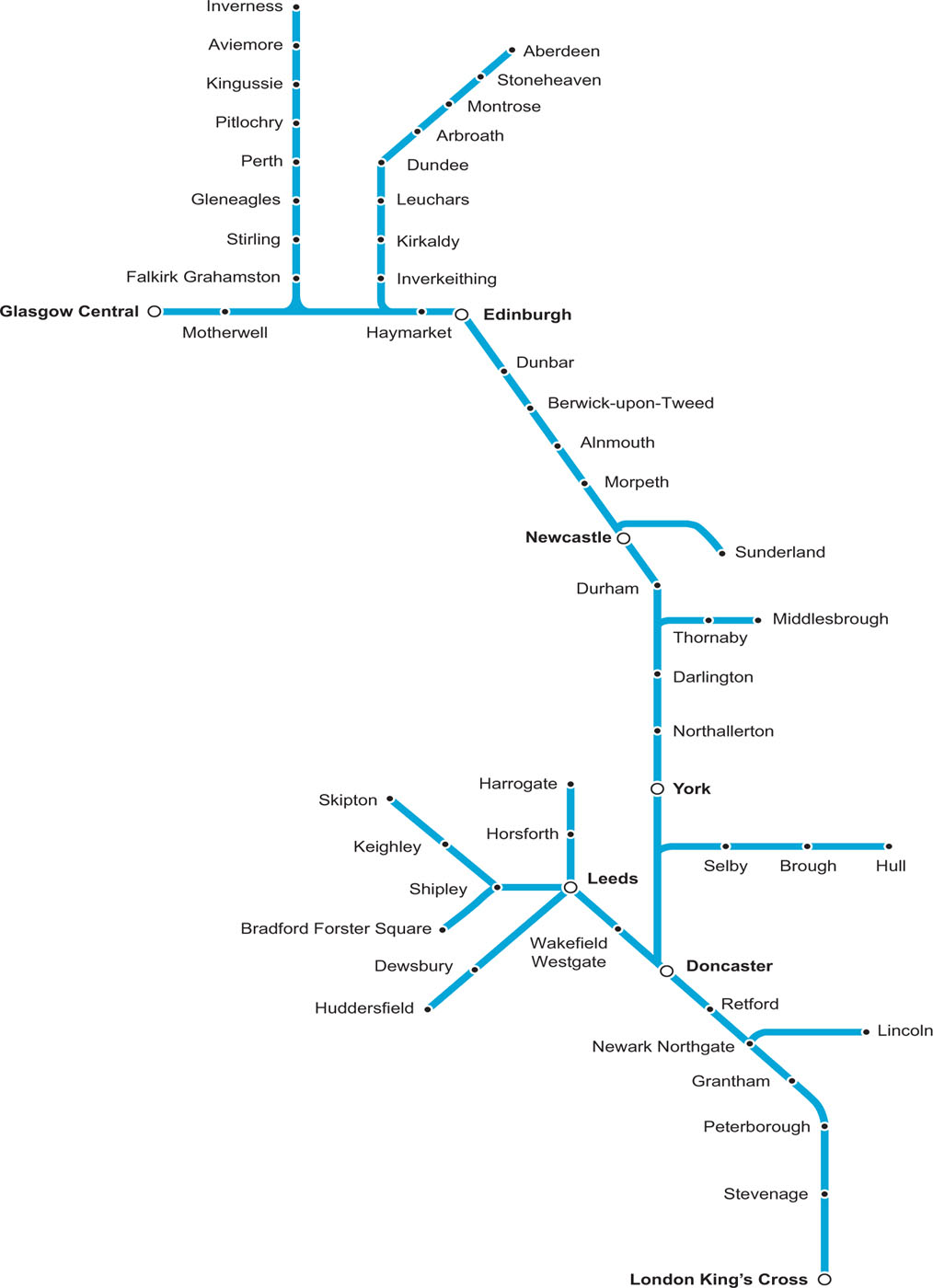

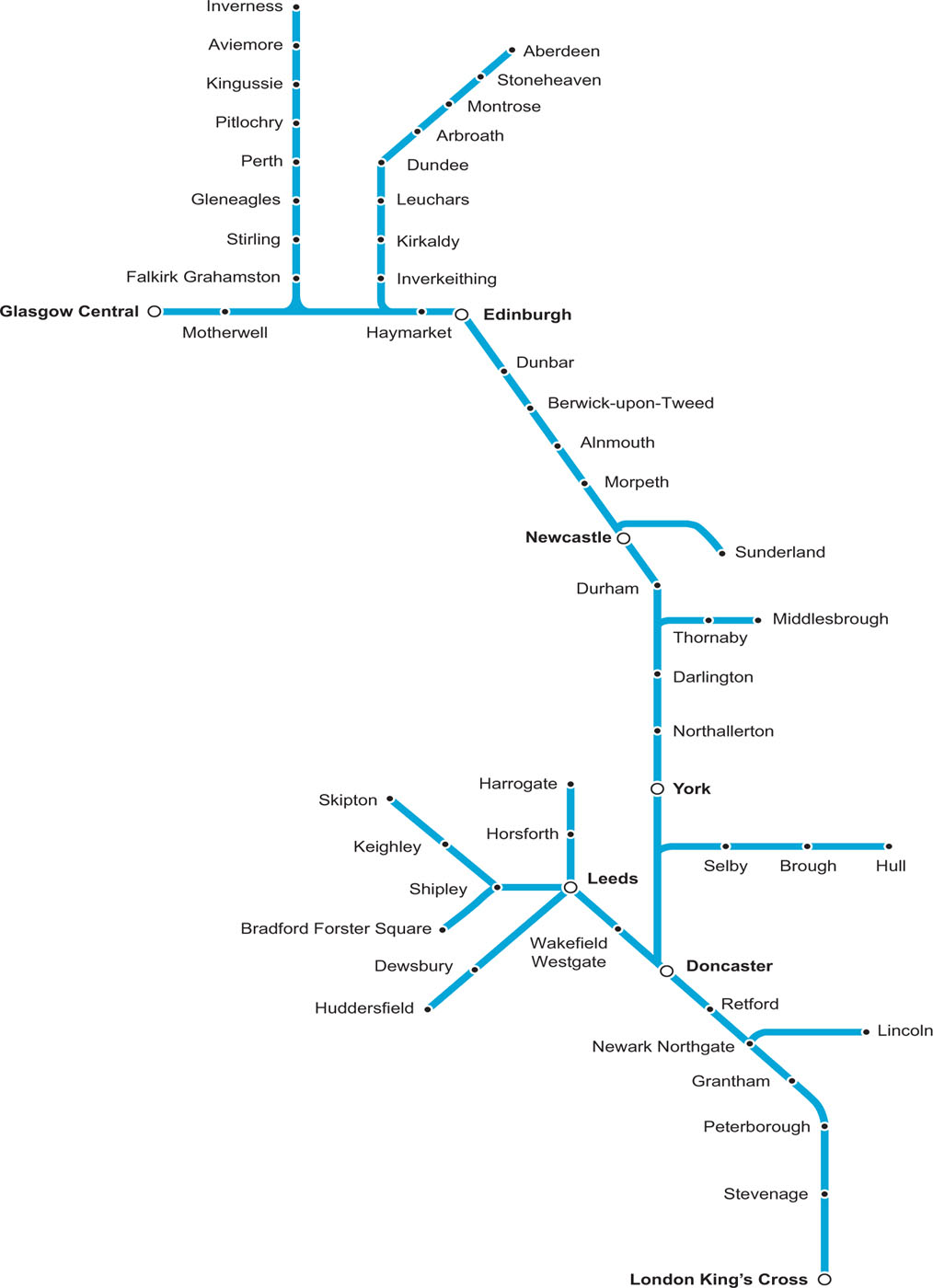

A 2010 Department for Transport route diagram of the East Coast Main Line from Kings Cross to Aberdeen and its principal connections.

Introduction

Steam hit the national headlines in a big way in 2016, with the return of the legendary Flying Scotsman to the nations railways after a lengthy absence, during which it underwent a major rebuild costing a phenomenal 4.2 million. Thus not only was it already the worlds most famous steam locomotive, but its overhaul under the auspices of owner the National Railway Museum also made it the worlds most expensive one.

The fact that we live in an age of celebrity culture was no more apparent than when the great Brunswick green behemoth returned to the tracks in triumph and began hauling passenger trains again. It is a gross understatement to say that crowds turned out everywhere it went: there were numerous instances of people trespassing on the lines to get a closer view, and on its official comeback trip from London Kings Cross to York on 25 February it had to be halted twice because onlookers were straying on to the electrified main line in complete disregard of their own safety. In fact the rail authorities stopped publishing its timings in a bid to deter trespassers, operators cancelled or rerouted two of its planned trips for fear that onlookers would stray on to the line side, and British Transport Police published photographs taken from a helicopter following at least one of its trains in a bid to identify and apprehend offenders. In short, Scotsman frenzy had gripped the nation: here was a train that had become almost too famous to run.

Flying Scotsman is, for many people, the defining icon of the steam age, and its exploits both in the steam era and its years in preservation never fail to enthral. Yet there is a far bigger story surrounding Sir Nigel Gresleys masterpiece not just concerning the locomotive, but also the route on which it staked its immortal claim to fame: Britains East Coast Main Line.

In 1706, the English Parliament passed the Union with Scotland Act, and the following year, the Union with England Act was passed by the Parliament of Scotland. The legislation brought to a conclusion a merger between two once-hostile countries, which had in effect begun with the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, when King James VI of Scotland inherited the English crown from his double first cousin twice removed, and a union of crowns took place, with both countries sharing one monarch for the first time. From 1 May 1707, the English Parliament and its Scottish counterpart united to form the Parliament of Great Britain, based in the Palace of Westminster. History recorded that the union took Great Britain to new political heights.

The following century the union of England and Scotland was further reinforced, not by further treaties, but by a 393-mile (632km) trunk railway. It reduced the journey time of five days or more between London and Edinburgh by stagecoach to just a few hours. In those days, such a feat was considered by ordinary folk as we might today regard daily commuter shuttles to a moon base and back: simply mind-blowing.

In the incessant drive by the railway companies operating over this trunk route to cut travelling time between the two capital cities, world transport technology jumped forwards in leaps and bounds, with Britain leading the steam era pack by a long way. There was open rivalry, firstly with the West Coast Main Line, which ran from London to Scotland on the opposite side of the country, and secondly with Germany, and this spurred on landmark developments in locomotive and infrastructure technology, leading to the golden age of steam in the Thirties.

In 1934 the London & North Eastern Railway A3 Pacific No. 4472 Flying Scotsman became the first in the world to officially break the 100mph (160km/h) barrier. Four years later another masterpiece was designed by the companys chief mechanical engineer Sir Nigel Gresley: the streamlined A4 Pacific No. 4468 Mallard, which set a world speed record of 126mph (203km/h) on Stoke Bank in Lincolnshire, snatching the crown off Nazi Germany. That world speed record has yet to be broken, and almost certainly never will be.

The great gateway to the East Coast Main Line: the frontage of Kings Cross station, as seen in the early LNER period. LONDON TRANSPORT MUSEUM

So not only did the East Coast Main Line make history by facilitating an ever-faster link between two capital cities, it also provided an international stage for Britains engineering marvels, inspiring many generations of schoolboys and adults alike. That was to continue after the end of the steam era on British Railways, with diesel and then electric traction setting a series of new records over the route.