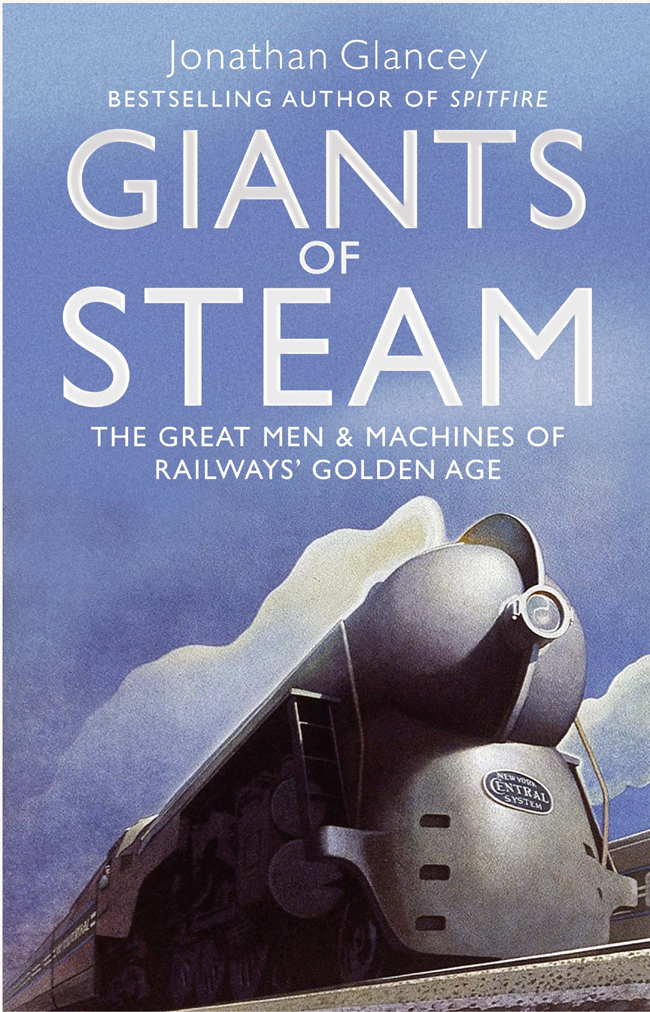

GIANTS

OF

STEAM

Also by Jonathan Glancey

The Story of Architecture

London: Bread and Circuses

Spitfire: The Biography

The Car: A History of the Automobile

Modern Architecture: The Structures That Shaped the Modern World

Architecture (Eyewitness Companion)

Lost Buildings

Nagaland: A Journey to Indias Forgotten Frontier

Tornado: 21st Century Steam

A Note on the Author

Jonathan Glancey is a frequent broadcaster and well known as the former architecture and design correspondent of the Guardian and Independent newspapers. He is also a steam locomotive enthusiast and pilot. His previous books include the bestseller Spitfire: The Biography.

First published in Great Britain in hardback in 2012

by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This edition published in Great Britain in 2014

by Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Jonathan Glancey, 2012

The moral right of Johnathan Glancey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission both of the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders.

The publishers will be pleased to make goodany omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

ISBN 9781782395669

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Atlantic Books Ltd.

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Here is the most marvellous of all machines... of which the mechanism most closely related is that of animals. Heat is the principle of its movement. It has in its various pipework a circulatory system like that of blood in veins with valves that open and close appropriately.

Bernard Forest de Belidor, Larchitecture hydraulique, vol. 2 (1739)

I cannot express the amazed awe, the crushed humility, with which I sometimes watch a locomotive take its breath at a railway station, and think what work there is in its bars and wheels, and what manner of men they must be who dig brown iron-stone out of the ground, and forge it into THAT! What assemblage of accurate and mighty faculties in them; more than fleshly power over melting crag and coiling fire, fettered, and finessed at last into the precision of watchmaking; titanium hammer-strokes beating, out of lava, these glittering cylinders and timely-respondent valves, and fine ribbed rods, which touch each other as a serpent writhes, in noiseless gliding, and omnipotence of grasp; infinitely complex anatomy of active steel, compared with which the skeleton of a living creature would seem, to careless observer, clumsy and vile.

John Ruskin, The Cestus of Aglaia (1865)

Somewhere in the course of manufacture, a hammer blow or a deft mechanics hand imparts to a locomotive a soul of its own.

mile Zola, La Bte Humaine (1890)

Steam has had a very good run for its money, and has lasted far longer than it was reasonable to expect. It has so lasted because retention of the pure Stephensonian form in its successive developments produced a machine which for simplicity and adaptability to railway conditions was very hard to replace.

E. S. Cox, Locomotive Panorama - vol. 2 - (1966)

PREFACE

THE OLD STRAIGHT TRACK

It was 10 oclock in the morning on Tuesday, 19 December 1933. Fog lay low across Swindon, the Wiltshire town that, since 1840, had been the mechanical heart of the Great Western Railway (GWR). The late-running Paddington to Fishguard express nosed its way cautiously west through the station and along past the great engineering works where its locomotive, 4085 Berkeley Castle, had been built eight years earlier. The driver of this fleet and powerful, 79 ton locomotive would have been unaware as the outer edge of its front buffer beam struck the bald head of an elderly gentleman who had been stooping down to inspect the condition of the tracks.

George Jackson Churchward, deaf and partially blind, was killed instantly. Colourful and autocratic, yet kindly and adored by his staff, he was already a legend by the time of his sudden death by steam, famed throughout Britain and its empire wherever a steel rail had made its impact on the landscape and the rhythmic beat of an engine could be heard. Born in 1857, the son of a yeoman farmer, in Stoke Gabriel, a village on the river Dart in South Devon, Churchward was one of the most important of all steam railway locomotive engineers, sharing a hall of fame with George and Robert Stephenson, creators of the steam locomotive as most of us know it, and Andr Chapelon, the French engineer who was taking this most charismatic and loved of machines to new heights of efficiency at much the same time as the GWR engineer was struck down by Berkeley Castle.

A part of the tragedy the stuff, in fact, of an ancient Greek play is that Churchward, the retired chief mechanical engineer of the GWR, was killed by one of his successors locomotives. It was as if the old king had been ritually slaughtered to make way for a new order. Certainly, Churchward was a very different character from Charles Benjamin Collett, the quiet, if forceful, engineer who had followed in his footsteps in 1921. Where Churchward was a radical, albeit one who looked and sounded like a tweedy English country squire, Collett was quietly conservative. Born at Grafton Manor, Worcestershire, a house built in the sixteenth century and rebuilt into the twentieth, he was educated at Merchant Taylors School before being apprenticed to a firm of marine engineers, after which he joined the GWR. He was happy to take up his predecessors mantle and to develop the hugely impressive machines for which the older man had been responsible, including the Saint and Star class passenger express 4-6-0s, which were among the most puissant and efficient of Edwardian steam locomotives. But where Churchward was very much a designer heading a highly talented design team, as well as an experienced workshop engineer, Collett was a production man, more interested in manufacturing at which he was very good than locomotive design.

The difference between the two one an outgoing fellow with a love of modern engineering and traditional country pursuits, the other an inward-looking spiritualist, hypochondriac, and keen vegetarian is well illustrated by a story from the mythology of Swindon works. One day, the pair were inspecting the fire-box of a locomotive together at the works. Pass me the illuminant, said Collett, a touch pompously, to a fitter, who had no idea what he meant. After a frustrating pause, Churchward popped his head out of the copper fire-box and barked, Pass the bloody light. Here was a man who was at once down to earth and highly imaginative. This has been a quality shared by all the truly great steam locomotive engineers; the steam railway engine has always responded best to those who are just as capable of wielding a heavy spanner as understanding the laws of thermodynamics.

Churchward was a consummate steam man. Unmarried, he dedicated his life when not out fishing to the development of the steam locomotive, in a career that began in 1873 with an apprenticeship at the South Devon Railway works at Newton Abbot. For him, the steam locomotive was as much a passion as a practical means of ferrying railway traffic. When teased about his bachelor status at a GWR dinner, Churchward retorted humorously: A lot of you are big men important men doing big jobs, where what you say goes. But what are you when you get home? Worms! Bloody worms! For Churchward, as for his great admirer Andr Chapelon, there was no time for wife or family. Their offspring, though, were some of the most impressive and best loved machines of any era or genre.