This book has taken some while to write, on and off over several years. Sarah Chalfant at the Wylie Agency suggested it to Julian Loose, my supremely patient commissioning editor at Faber. I would like to thank them both very much indeed. Thanks, too, to Kate Murray-Browne for guiding the book through the production process and to Trevor Horwood for his meticulous copy-editing and many useful suggestions. Peter van Ham and the late Jamie Saul travelled extensively through Nagaland between 1996 and 2006, their journeys overlapping my own. Peter has kindly provided his and other photographs of rural Nagaland together with images from the extensive Macfarlane Archive of which he, as chairman of the Society for the Preservation and Promotion of Naga Heritage in Frankfurt, is custodian. Jamie died in the Burmese Naga Hills in 2006. Their book, Expedition Naga is a beautifully illustrated and revelatory travelogue following in the remote footsteps of the European district officers and anthropologists of the 1920s and 1930s. I am indebted to them both. Above all, my thanks are to the people of the Naga Hills who have let me see so much of their beautiful, if challenging, country. Their names are mostly left unrecorded. This, however flawed, is their story.

While acknowledging new names for cities and countries, I have in most instances used, for claritys sake, those best known over the centuries to Nagas, Indians, Burmese and British alike.

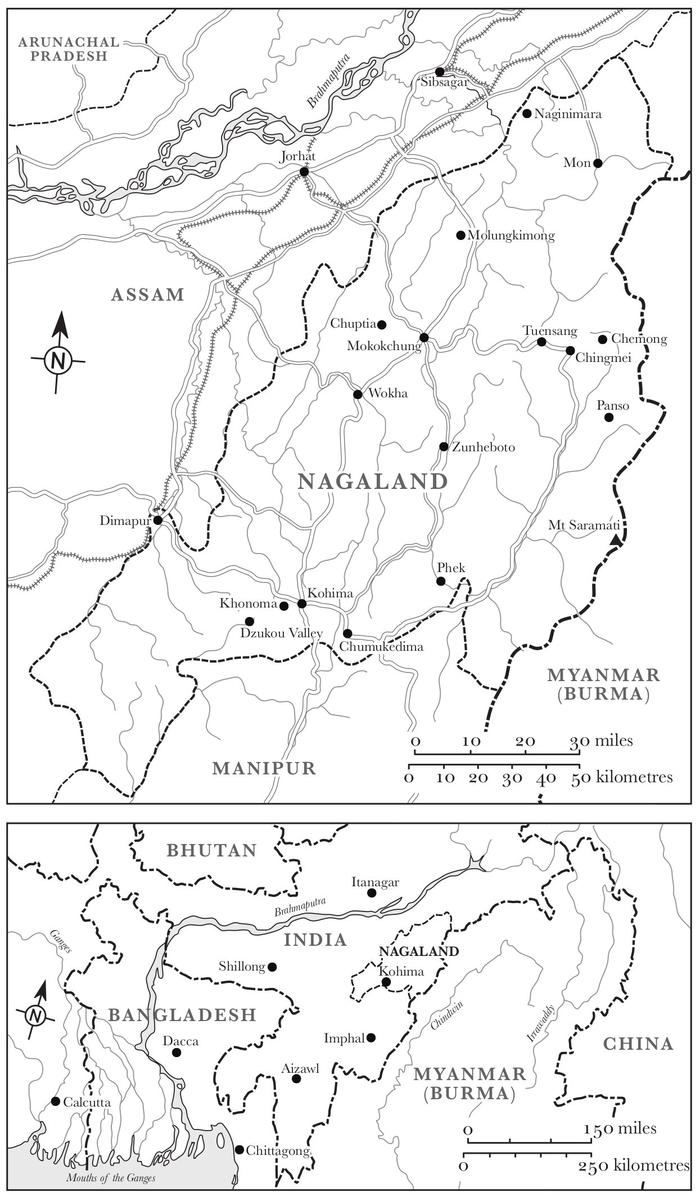

Landlocked, and largely inaccessible to foreigners, Nagaland is one of the youngest and certainly the most hidden state of modern India. Cut off from the rest of the world at the eastern hem of the Himalayas, it is home to nearly two million people from some sixteen Tibetan-Burmese tribes who have been fighting a remote and rarely reported war for independence from India, on and off, since the early 1950s. The fighting continues sporadically, skirmishes between rival independence movements and against Indian armed forces undermining fragile treaties while tourists, some apparently unaware of the struggle being fought around them, continue to enjoy the more peaceful areas of the state.

Nagaland is tucked into the far north-eastern corner of India. It borders the states of Assam, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh and, across an international frontier, the Union of Myanmar, once known as Burma. But up to a further two million Nagas live outside the states borders. For many of them Nagaland, which has existed as a state only since 1963, is an Indian fabrication that fails to recognise their nationhood: a fragmentation of their natural homeland by politically expedient boundaries. What Naga independence movements and guerrilla armies have been fighting for over several decades is the dream of Nagalim, or a Greater Nagaland, an independent country that would unite all the tribes in a land of their own. As this book hopes to explain, their dream remains just that, and may do for many generations to come.

Here is a remarkable place Shangri-La through a glass darkly a people, and a war without end, largely unheard of outside the Indian subcontinent, and not much known even within it. Nagaland is a place of stunning beauty, a once-flourishing secret garden blighted by war and effectively cordoned off from the rest of the world. More than 200,000 people have died here in seven decades of brutal conflict while its political masters, despite numerous short-lived peace settlements over the years, maintain a heavy-duty military presence in the region. The Nagas, however, remain unwilling to settle for anything less than a much greater degree of freedom than the government of India is ever likely to sanction.

I had wanted to visit this high and haunting land since I was a small boy. My father, Clifford George Glancey, a child of the Raj born in Lahore, and my grandfather, George Alexander Glancey, an Anglo-Irish Indian Army general, knew Nagaland well. It was then the partly unexplored Naga Hills district of Assam, the great tea-growing region, where my uncle Reg, a future Eighth Army officer, was a planter. He spoke fondly of the Naga people. They were, he said, headhunters. But they were also hospitable, loyal, brave and passionately fond of music, dancing, hunting and extravagant costumes. They lived in remote regions of lush hills and valleys patrolled by tigers, and across the Burmese border in self-governing highland villages.

My father returned to the region with the RAF in 1944, when Commonwealth forces and Naga warriors loyal to the British drove the Japanese back from the Indian border to Burma and the tropical seas. The Japanese had hoped to reach Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Delhi through the Naga Hills. Had they done so, they would have broken the back of colonial India and of the British Empire itself.

My father said I would enjoy a trek to Burma from India through Assam and the Naga Hills. This, tricky enough in his day, is more easily said than done in mine. For many years Nagaland has remained a dream destination, much as Kafiristan had been for Brothers Daniel Dravot and Peachey Carnehan, Freemasons and soldiers of fortune, in Kiplings The Man Who Would Be King, a short story that I read over and over again as a boy. In 1975 it was made into an equally enjoyable and compelling film, directed by John Huston and starring Sean Connery and Michael Caine, renewing my enthusiasm for some unknown, mythical Asian world beyond established frontiers.

What few written references I came across to Nagaland as a boy were, however, hardly encouraging. I remember buying a second-hand paperback copy of H. E. Batess The Jacaranda Tree at a time when this author was best known for his frightfully English novels Love for Lydia and The Darling Buds of May, but not for the stories he wrote as Flying Officer X for the RAF during the Second World War. Bates developed one of these into The Jacaranda Tree, published in 1949. It tells the story of English settlers in Burma making a tragic escape to India with the Japanese army in hot pursuit. Led by Paterson, manager of a rice mill, their route would take them north through Naga territory:

The hills might be tough, but he knew the road, if you could call it a road, for about a hundred and twenty miles northwestward, roughly in the direction of Naga country, but beyond that he did not know it and there were few who did. He could only guess what lay there. Soon the scraped-out terraces of blistered rice-field would give way to the wretched fields where nothing grew but the thinnest sesasum and millet where in harvest the flocks of raiding paroquets were like hordes of banana-green locusts ravaging the seed. It had always been a country of continual exodus up there: a wandering from place to place by thin cattle, lean men, sore-eyed children, women with faces of teak-wood, an endless search for the hills less bitter places. And soon all that would go, to be replaced by the folded parallels of forested rock, basaltic, bitter, waterless, like hills of iron veiled with minutest cracks of sand scorched to whiteness by the long dry season, mockingly like rivers between the great sunless towers of forest and bamboo It was not the things that lay behind that troubled him but the things that lay in front of him. If he feared anything at all it was that the road might die up there, somewhere in the high jungle, between the foothills where they now were and the far tea country of Assam.