EMPEROR HIROHITO

AND

THE PACIFIC WAR

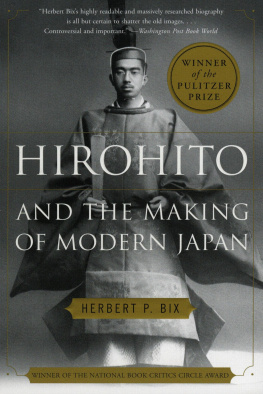

Emperor Hirohito in the uniform of army commander in chief, ca. 192829

EMPEROR

HIROHITO

AND

THE PACIFIC WAR

NORIKO KAWAMURA

NORIKO KAWAMURA

2015 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United State of America

Composed in Warnock, a typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

19 18 17 16 155 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kawamura, Noriko, 1955

Emperor Hirohito and the Pacific war / Noriko Kawamura.

pagescm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99517-5 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Hirohito,

Emperor of Japan, 19011989. 2. World War, 19391945Japan.

I. Title.

DS889.8.K3959 2015

940.54'26dc23

2015020141

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials,

ANSI Z39.481984.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 The Aftermath of the

Paris Peace Conference, 19191933

CHAPTER 2 Crises at Home and Abroad: From the

February 26 Incident to the Sino-Japanese War

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FROM INCEPTION TO COMPLETION, THIS STUDY OF EMPEROR Hirohito and the Pacific War has covered many years of my career as a historian. Robert J. C. Butow first encouraged me to pursue the topic and warmly supported me throughout the process. Without his encouragement and advice, I would not have been able to bring this project to a successful conclusion. Wilton B. Fowler offered me the foundational training that shaped me as a diplomatic historian with keen interests in historical issues of war and peace. Kenneth B. Pyle guided me in the study of modern Japanese history in the English-speaking world. In the early stage of my research in Japan, Akira Yamada and Hisashi Takahashi showed me divergent ways to approach the project and helped me with archival research. I also want to thank numerous people who assisted me at the National Diet Library of Japan, the National Institute for Defense Studies (Boeikenkyujo), and the Imperial Household Agency (Kunaicho). As this project progressed, many scholars gave me helpful suggestions and comments. I want to especially thank E. Bruce Reynolds, Michael A. Barnhart, Barton J. Bernstein, and Fredrick Dickenson. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Richard H. Minear for reading the entire manuscript and giving me useful suggestions. In addition, I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to Lorri Hagman of the University of Washington Press for her kind support and to Alice Davenport, Ernst Schwintzer, and my husband, Roger Chan, for editorial assistance.

EMPEROR HIROHITO

AND

THE PACIFIC WAR

INTRODUCTION

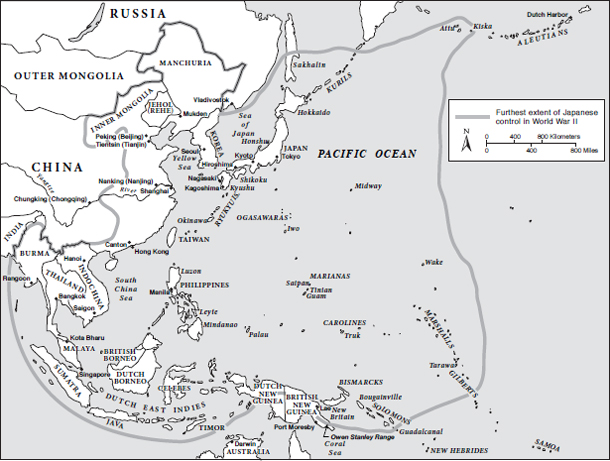

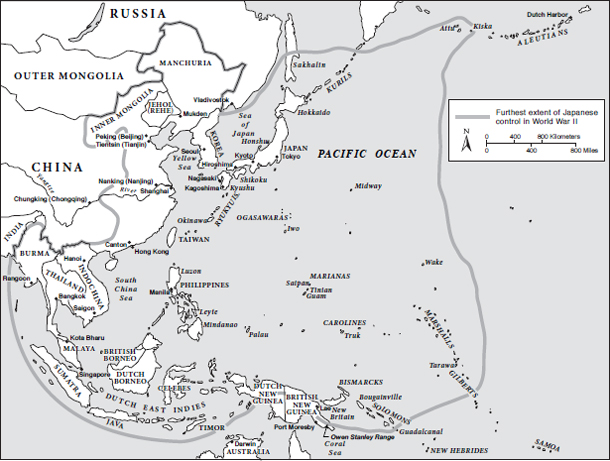

WORLD WAR II CREATED MANY HEROES AND VILLAINS. Emperor Showa, better known in the United States as Emperor Hirohito, has been one of the most controversial figures in the history of the war that Japan waged in Asia and the Pacific.

Japan fought the Pacific War to the bitter end in order to preserve its kokutai (national polity), for which the myth of imperial rule served as core. Nevertheless, upon Japans surrender to the Allied Powers, Hirohito, who renounced his divinity in his public declaration of humanity, was altogether spared the postwar Tokyo war crimes trial. He continued to reign in postwar Japan until his death in January 1989, serving as the symbol of the state and of the unity of the people under the new democratic constitution, which was essentially written by the Americans who occupied Japan from 1945 to 1952. This dramatic shiftfrom a divine absolute monarch under the prewar constitution to a humanized symbolic emperor under the postwar democratic constitutioncreated numerous historical narratives of two diametrically opposed images of Hirohito, before and after Japans war in Asia and the Pacific. These two contrasting images of Emperor Hirohito have fueled debates over his wartime responsibility, which remains a potentially explosive issue between Japan and former victims of Japanese military aggressions abroad, as well as a troublesome issue within domestic Japanese politics. Historians, in todays politically and ideologically partisan environment, continue to debate the power the emperor possessed and the role he played during the war.

As told from the United States point of view, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and pulled the United States into what Americans call the Pacific War on December 7, 1941, Emperor Hirohito became the countrys public enemy number one. Polls taken between 1943 and 1945 indicated that a third of the US public thought Hirohito should be executed, and even after Japans surrender, the US Congress passed a joint resolution demanding that he be tried for war crimes. Finding the answer to this particular question was vitally important to MacArthur and his staff and reflected their own assumptions and preoccupations.

In the end, the emperor was excluded from the entire process of the Tokyo war crimes trial and became the most useful ally of SCAPs reform efforts in occupied Japan. The Tokyo tribunal placed the blame for a reckless and aggressive war on the military, the ultranationalists, and the zaibatsu (financial cliques). The verdicts of the war crimes tribunal provided the basis for the postwar orthodoxy that portrayed Emperor Hirohito as a peace-loving constitutional monarch, who could not prevent the military from starting aggressive wars in Asia and the Pacific but who was nevertheless able to preserve his defeated nation from annihilation through his decision to end the war in August 1945. But the basic questionwhy did the emperor permit the war to begin in the first place?was never fully answered at the time and haunted him thereafter.

Over the past seventy years, numerous analyses by Japanese scholars and journalists have kept within the bounds of the generally accepted postwar interpretation of the emperor, although their arguments reflect various shadings and show the authors sensibilities to the complexity and nuances of the issue. Such Japanese studies explicitly or implicitly reinforce the orthodox view of Emperor Hirohito as a peace-minded constitutional monarch, and

More recently, leftist historians in Japan have challenged what they call the Tokyo Trial view of history advocated by so-called palace group historians and have criticized the emperors failure to take responsibility for starting the war. This leftist interpretation of Emperor Hirohito gained momentum after his death in January 1989. Utilizing primary sources that became available in the 1990sincluding diaries, letters, memoirs by persons close to the emperor, and records of the emperors own wordsthe postwar generation of leftist historians has been trying to bring the emperor to trial in the court of history. By focusing on his role as

Next page

AND

AND  NORIKO KAWAMURA

NORIKO KAWAMURA