PRAISE FOR

NORMA FIELDS

IN THE REALM OF A DYING EMPEROR

Powerful a searing, persuasive indictment.

Elisabeth Bumiller, Washington Post Book World

In a style packed with poignant details, important facts and vivid historical description, Field analyzes issues of class, ethnicity and gender, further exploring the murky separation of church and state in contemporary Japan One of the most original and insightful discussions to emerge from recent Japan scholarship.

San Francisco Chronicle

Brilliant At a time when America and Japan administer nasty bashings to each other on a daily basis, the deeper understanding of Japanese society provided by Norma Field is vital. She bridges the two cultures and dramatizes as few writers could the pitiless price exacted from those ordinary Japanese who made high growth economics possible.

Chicago Tribune

Rich and complex.

The Economist

In this remarkable book, Norma Field returns to the land of her birth and examines it through the lens of its own taboos by portraying stories of people who have transgressed them. In the Realm of a Dying Emperor is the most insightful book about modern Japanese society that has come along in a decade. Fields ironic yet sympathetic style is both engaging and compelling.

Far Eastern Economic Review

Poignant a riveting portrait of contemporary Japan. Field is able to elicit rich personal histories from her interviewees [and] we see them as individuals. [In the Realm of the Dying Emperor] provides a much-needed assessment of modern Japan.

Seattle Weekly

A deftly crafted and politically timely book. Miss Field is a rare cultural go-between. The power and authenticity of her text derive from a unique ability to approach the issues with the political ideals and analytical mind of an American scholar while describing Japanese culture with the sensitivity of a Japanese raised in Japan.

Washington Times

In these moving portraits from beyond the pale, Field provides a complex social topography in which the tenacity of dissent is pitted against the tyranny of common sense. Field seeks the conscience of [Japan] and finds it memorably.

Times Literary Supplement (London)

Evocative moving The reader sees the connection between the personal and the political in this book, and this is perhaps what makes it successful. This is a powerful book precisely because it is written with passion [and] the painful and often powerful reflections of a sensitive author.

The Japan Times

[Field] anatomizes the Japan she knows in a stylish, brilliantly written, introspective book. In the Realm of a Dying Emperor draws its power not only from Fields personal experience and her expertise as a leading scholar, but from her courage in tackling the whole subject of Japanese inhibitions about their society in such a vivid, compelling way. Makes all other books about Japan obsolete, uni-dimensional and somehow irrelevant.

Edward Behr, author of Hirohito: Behind the Myth

NORMA FIELD

IN THE REALM OF

A DYING EMPEROR

Norma Field was born to a Japanese mother and an American father in Occupation Japan. She currently teaches Japanese literature as an associate professor at the University of Chicago. She is the author of The Splendor of Longing in the Tale of Genji , and the translator of And Then by Natsume Sseki.

ALSO BY

NORMA FIELD

THE SPLENDOR OF LONGING IN THE TALE OF GENJI

For Maia and Matty

and the children with whom

they must make a world

CONTENTS

I

II

III

PREFACE

EMPEROR HIROHITO of Japan, posthumously known as Emperor Showa, collapsed on September 19, 1988, and died on January 7, 1989. His state funeral, evidently attended by more foreign dignitaries than any other funeral in world history, took place on February 24. Those five-and-a-half months were lived with particular intensity by most Japanese. For the first time since the nation had been transformed by economic prosperity, there was an attempt to reflect on World War II and its legacy, especially on the role of Japan as aggressor as well as victim. At the same time, such newly critical reflection was truncated or repressed altogether by a spectacular exercise in self-censorship.

This book is a meditation on the death of Hirohito, the deaths in the Pacific War (the Fifteen Year War), and the death-in-life quality of daily routine in the worlds most successful economy. It is also an act of paying homage to those who resist the comforts of amnesia and the lure of fabulous consumption, who insist on thinking of the past and the present against each other.

More literally than many books, this book depends on others for its existence. My heartfelt thanks to all who appear in it for the generosity of time and spirit they extended to a stranger. My profound debt to family members who are part of this book can only be acknowledged, never discharged. This book is a modest tribute to them, too, especially the womenfolk who raised me with grace at such cost to themselves.

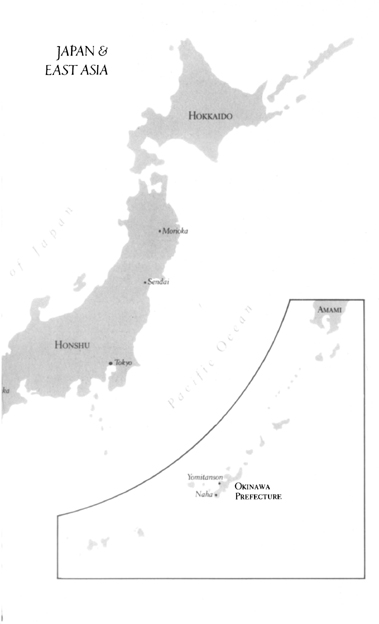

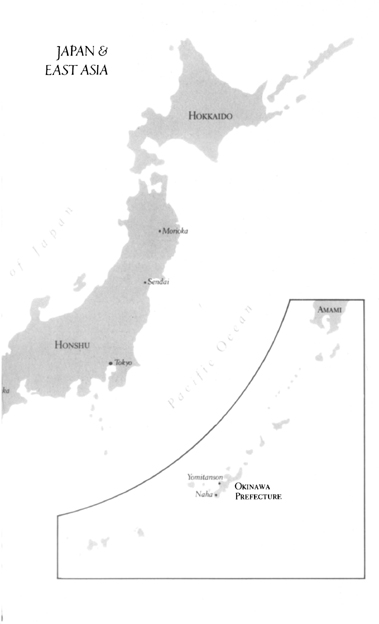

In Okinawa I was guided materially and conversationally by Hiyane Miyoko and Teruo, Kakazu Katsuko, Miyagi Harumi, Shimabukuro Toshiko, Shimojima Tetsur, Takara Ben, and Terukina Kei. I am also grateful to Kamiyama Shigemi, Mura-tsubaki Yoshinobu, and Yoneda Masaatsu of Siglo, Ltd.

In Yamaguchi, Urabe Yoriko and Yabuki Kazuo were generous with their insights and hospitality. Hayashi Kenji, Imamura Tsuguo, and Tanaka Nobumasa helped me understand the Christian struggle in modern Japan.

Brian and Michiko Burke-Gaffney, Iwamatsu Shigetoshi, Tsuchida Teiko, and Harada Na, together with all those drawn to his two-room publishing house, had a hand in the Nagasaki chapter.

The poets Chong Chuwol and Michiura Motoko have a special place in the journey underlying this book.

Kuriyama Masako generously advised and facilitated.

Old and new friends sustained the actual writing by reading the pieces I thrust upon them. I wish I could thank each of them with the particularity they deserve. Ren Arcilla, Bill Brown, Celia Homans, and Richard Rand expressed unrequired enthusiasm that proved essential through fainthearted periods.

Leslie Pincus and Miriam Silverberg grubbed through the manuscript. Their comments became steadfast companions, prodding me through my self-doubting revisions.

Finally, there is Maria Laghi, who was there in the beginning to make it all possible.

Following Japanese custom, I have cited Japanese names surname first. I have also adopted the forms of reference and address prevailing in their communities for Chibana Shichi, Nakaya Yasuko, and Motoshima Hitoshi: thus, Shichi, Mrs. Nakaya, and Mayor Motoshima or simply, the mayor. Titles of Japanese works are given in English translation in brackets. Subsequent references will be to an abbreviated version of the translated title. Except for citations from the official translations of the Imperial Rescript on Education of 1890 and the postwar Constitution, all translations from Japanese-language sources are my own.