FOREWORD

C an history be shared? This is the key question Laurence Rees raises in this important book. And the book gives a resoundingly affirmative response to that question.

There is a temptation to view a nations past primarily, if not entirely, in the national framework: to consider its history as sui generis , a product of its own culture, to be understood in the context of its own indigenous development. A recent school textbook in Japan one that has aroused a storm of protest from Korea, China, and other countries states that there are as many histories as there are nations, with the implication that a countrys history must be comprehended, appreciated, and judged in terms of its peoples ideas, interests, and values. Defenders of this sort of self-centred nationalism and such people are found everywhere believe that a given people understand their history better than other peoples, and that foreigners should not stand in judgment over it.

Horror in the East , both as a documentary and as a book, takes the opposite view. It has been produced on the assumption that the past must be shared, that it is open to anyone to examine, and that the quest for historical understanding knows no national boundaries. Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Filipinos, Australians, Americans, British, and others who appear in the book (and in the documentary film) all seek to understand, whether as participants in past dramas or as contemporary commentators, the human tragedy that was the horror in Asia during the Second World War.

To speak ofhorror, of course, implies moral judgment. But the judgment is not necessarily that of one nation condemning another nation, for no nation is free of moral culpability. Rather, the judgment is, first, the application of universal human standards to specific deeds of barbarism committed by individuals; it is, second, an effort to understand why atrocities of such magnitude were perpetrated at specific moments in time; it is, finally, an act of linking the present to the past in which todays generation speaks to an earlier generation.

The book is rich in detail, containing some episodes the BBC team discovered in dust-covered archives in Japan, the United States, Britain, the Netherlands, Australia and elsewhere. The interviews, especially of Japanese veterans, are vivid reminders of what it was like to live, and to face certain death, in the valley of darkness, the term that is often used to describe the war years. There are no taboos in the story; Rees, for instance, asks pertinent questions about the role of the emperor and examines them dispassionately, avoiding dogmas and emotional rhetoric. Above all, the book succeeds in putting Japans wartime policies and behaviour in the context of a conformist society under pressure. As one who grew up during the war I was in fifth grade when the war ended I can attest to the truth of this argument. The power of conformism, the ardent wish not to be different, a misguided sense of honour which dictates that dissent will disgrace the nation, the family, and yourself these traits still exist in Japan, and in many other countries, today. But the book suggests that there are others, those who are willing to speak candidly about the past, not merely among themselves but also with people from other lands. To the extent that Horror in the East reveals the existence of such people, the book points to the emergence of an international arena where memory and history may be shared and openly discussed, where what the author aptly refers to as a common thread transcending national or cultural differences may be found.

Professor Akira Iriye

Harvard University

INTRODUCTION

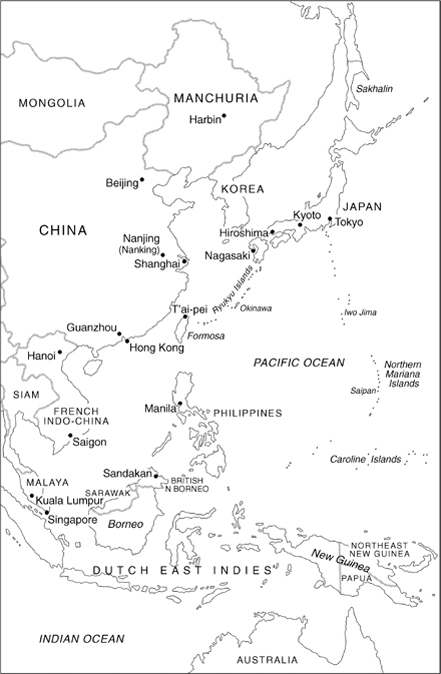

I nscrutable that is the adjective most often used to describe the Japanese. And on the face of it, what could be more inscrutable than their actions during the Second World War? Their attack on Pearl Harbor, their worship of their emperor as a God, their willingness to die in kamikaze attacks, their appalling treatment of Allied prisoners of war, their war crimes against women and children in China all these actions and more are hard, if not impossible, for Westerners to understand.

I fully expected to run into this concrete wall ofinscrutability in our quest to understand why the Japanese acted as they did during the war just as I had when, years before, I had asked an intelligent, sophisticated Japanese friend what she knew about the most infamous atrocity committed by the Imperial Army, the Nanking massacre of 1937. Ah, she replied, smiling, I did study history at school, but you must understand, Japanese history is many thousands of years old and very complex. Its a very, very big book we have to study. And, of course, we start at the beginning of the history and study hard and in detail. So, unfortunately, by the time I left school we hadnt finished the whole history....I think perhaps we stopped at the end of the nineteenth century. We just didnt get around to looking at the Nanking massacre.