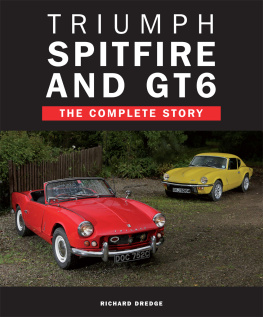

SPITFIRE

First published in Great Britain in hardback in 2006 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This edition published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Jonathan Glancey, 2006

The moral right of Johnathan Glancey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission both of the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders.

The publishers will be pleased to make goodany omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

eISBN 9780857895103

All technical drawings by Mark Rolfe Mark Rolfe Technical Art

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Atlantic Books Ltd.

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

I can hardly better the dedication Alfred Price made in his excellent Spitfire: A Complete Fighting History to the men and women who transposed the Spitfire a mere fabrication of aluminium alloy, steel, rubber, Perspex and a few other things into the centrepiece of an epic without parallel in the history of aviation.

Nonetheless, I would like to add my own to the infamous memory of Britains New Labour governments, their love of ill-founded war and their authoritarian fight, undertaken with greater effectiveness than the Luftwaffe, to undermine those civil liberties and hard-won traditions of freedom fought for by decent people over many centuries, and especially by those, of whatever nationality, class, creed, colour, age, gender or political affiliation, who designed, built and flew the Spitfire.

And in loving memory of my father.

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

SPITFIRE

INTRODUCTION

I Ts the sort of bloody silly name they would give it. R. J. Mitchell, inventor of the Spitfire, the most famous, best-loved and most beautiful of all fighter aircraft, was not exactly impressed by the tricksy appellation some cove flying a desk in Whitehall is said to have come up with for his prototype Supermarine Type 300 monoplane. The aircraft answering to Air Ministry specification F.37/34 had, in fact, been named by Sir Robert McClean, chairman of Vickers, the company that had bought the Supermarine Aviation Works, after his young daughter Anna, a right little spitfire. As for Merlin, the name given to the magnificent 1,000-hp Rolls-Royce V12 aero-engine that powered the Spitfire, this had been a wonderfully apt choice by Rolls-Royce itself. The Merlin proved to be the stuff of mechanical wizardry and, as the loudly beating heart of the stunning little fighter aircraft that soared into British skies against Hitlers Luftwaffe in 1940, it was a significant part of the spell, and more than a flash of the sorcery, that led to the Nazis Gtterdmmerung in 1945.

Rolls-Royce had actually named what was to become its most famous aero-engine not after the Arthurian wizard but after the falcon the Americans know, rather prosaically, as the pigeon hawk, and the British, more poetically, as the merlin. Rolls-Royce had a policy of naming its engines after birds of prey the Eagle, Kestrel, Peregrine, Griffon and Vulture were all installed with varying degrees of success in RAF aircraft. The Merlin, though, was a perfect match from the very start for Mitchells promising little fighter. The avian merlin is a raptor with thin, pointed wings that allow it to dive at sensational speed. The Spitfires famously thin wing enabled it too to dive at very great speeds, so much so that in 1943 one of Mitchells sensational machines was not so very far from breaking the sound barrier. Not that a piston-engined aircraft ever has achieved this; it took the custom-designed and rocket-powered Bell X-1, Glamorous Glennis, to do the job in October 1947 with Captain Charles Chuck Yeager at the controls. During the Second World War, Yeager had flown the North American P-51D Mustang, a superb American fighter powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin, built under licence by Packard in Detroit. It was also the stuff of aeroindustrial sorcery.

The fastest falcon of all, the peregrine, can reach a speed of up to around 200 mph in a headlong dive in pursuit of its prey. The Victorian Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins evoked the flight of one of these mercurial raptors in an exhilarating, tongue-tripping poem, The Windhover:

I caught this morning mornings minion,

kingdom of daylights dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skates heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

When I first read those words, dedicated by the poet to Christ Our Lord, I was a schoolboy at what I thought of as a Catholic Stalag Luft. I was fascinated by birds and in love with aircraft and the idea of flight, and I thought of Hopkinss falcon as a Spitfire scything through the air, off forth on swing as a skates heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend. It was as if Hopkins had actually seen a Spitfire, another kind of saviour, in flight although if he had, he would surely have described the sound of the Merlin engine that accompanies the flight of this most dangerously exquisite mechanical bird of prey. The Merlins voice is all thunder and lightning, a deep, pulsing roar overlain with the throaty whistle of its supercharger.

Rumble thy bellyful! Spit, fire! spout, rain! Even in this line from Shakespeares King Lear (Act 3, scene 2) that I happened to alight upon at much the same time as I flew on minds wings with Hopkinss falcon, I could hear the basso profundo thrum of a Merlin and the blazing sight and chattering sound of Browning .303 machine-guns, or the pom-pom thud of Hispano 20-mm cannon, raining revenge from the wings of a fighter that really did spit fire.

Of course, for any English schoolboy of my generation who could assemble 1/72 scale Airfix Spitfires a squadron of them, in fact, lovingly painted and detailed, complete with oil leaks from their glossy black Merlins and do so without spreading strands of Britfix 77 glue and telltale fingerprints across their Lilliputian windscreens, there was another poem, that those who loved aircraft, yet pretended not to care a fig for literature, knew by heart:

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward Ive climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds and done a hundred things