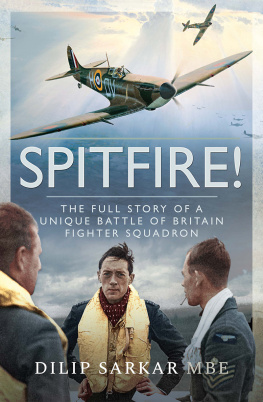

Sadly, not only servicemen and women, and their families, suffer in time of war. On 24 September 1940, Supermarines Spitfire factory at Woolston in Southampton was successfully attacked by Erprobungsgruppe 210s fighter-bombers. The two youngest casualties beside the River Itchen that day were Douglas Cruickshank, a workshop assistant, aged fourteen, and nineteen-year-old Margaret Anne Moon, a typist. It is to those two teenagers that this book is respectfully dedicated.

First published 2013

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Dilip Sarkar, 2013

The right of Dilip Sarkar to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 9781445605852

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 11pt on 12pt Sabon LT Std.

Typesetting by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The Supermarine Spitfire is the most charismatic and inspirational fighter aircraft ever built. Fascination for it certainly shows no sign of abating. In this book, therefore, I have tried to put the Spitfire into its design and operational context mainly through the use of original photographs. Whereas my previous works have concentrated on the human experience connected with the Spitfire, this book focuses on the aircraft itself. The photographs are from a variety of sources, mainly from the personal collections of pilots and support staff. Although not of a professional photographers standard, these nonetheless provide a unique window through which we can still glimpse the past and are often much more interesting and revealing than the officially sanctioned images so widely available today. Sadly, most of the contributors are now deceased, but I remain grateful to all for their friendship and co-operation. The Spitfires Finest Hour was, of course, during the early war years, so I make no apology for having allocated more photographs to the years 193641.

I would also like to thank Roger Henderson, Henry Fargus, Steve Bown and Garry Campion for adding several extra illustrations, and my publisher, Jonathan Reeve, for suggesting this book. Indeed, I look forward to publication of Rogers book, The Channel Front: A Chronicle of 19 Squadron at War, 194142. Rob Rookers boundless enthusiasm for all things related to 152 Hyderabad Squadron led to him founding and maintaining what is undoubtedly the best squadron-based website available: see http://www.152hyderabad.co.uk. Rob has also collected numerous photographs from veterans, and I am particularly grateful to him for contributing a number of them to this project.

My wife, Karen, of course, has my love and gratitude for her continued, unfailing, and essential support.

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS BA(Hons),

Worcester, 26 April 2013

1

A REAL KILLER FIGHTER: 19361939

In the psyche of the British public, R. J. Mitchells Supermarine Spitfire was a winner from the outset. This was not just because of its stunning sleek lines, elliptical wing and high performance, but because the Spitfire was a direct descendant from Mitchells famous Schneider Trophy-winning British seaplane racers. This spectacular competition took place between 1919 and 1931, aircraft racing at low level over water, providing a breathtaking spectacle for spectators. The matter became one of great national pride. Aircraft designers began pushing the boundaries, breaking away from the traditional biplane and producing faster and more streamlined monoplanes. Mitchell, the chief designer of Supermarine at Southampton, was at the forefront of this development. In 1927, Mitchells S5 achieved first and second place, setting a new air speed record of 281.66 mph. In 1929, the improved S6 won again, with an average speed of 328.63 mph. Afterwards, the S6 was confirmed as the fastest and most technologically advanced aircraft in the world when Squadron Leader Orlebar set a new world record at 357.7 mph. Britain needed one more consecutive victory to permanently retain the coveted silver trophy but the dreadful Wall Street Crash dictated the withdrawal of government funding for the next race. An eccentric patriot, Lady Houston, incensed at the prospect of Britain being unable to compete, then wrote a cheque for 100,000 enabling Mitchell to win the Schneider Trophy in 1931 with the S6Bs staggering 340.08 mph. In spite of the seaplanes high performance and the patriotic fervour generated by the race, the RAFs Air Member for Supply & Research, Air Vice-Marshal Hugh Dowding, considered the racing seaplanes useless for military purposes. Nonetheless, Dowding had recognised the clear superiority of monoplanes, leading to the issue of Specification F7/30 on 1 October 1931, which invited private tenders from aircraft designers to produce a new fighter for the RAF. As Dowding said, I wanted to cash in on the experience gained in aircraft construction and engine progress. The Spitfire story had begun.

The requirements for F7/30 were:

1. Highest possible rate of climb.

2. Highest possible speed at 15,000 feet.

3. Fighting view.

4. Manoeuvrability.

5. Capability of ease and rapid production in quantity.

6. Ease of maintenance.

The Air Ministry also required the new fighters maximum speed to be at least 250 mph, and for it to carry four machine-guns. Surprisingly, Gloster Aircraft won the competition with a radial-engined biplane, the SS37, although this never entered production. Fortunately the Air Ministry recognised that the designs edge in performance was insufficient, meaning that it would soon become obsolete. Mitchell had found F7/30 too restrictive to produce an aircraft of the highest possible performance. Consequently Supermarine and aero-manufacturer Rolls-Royce decided to privately collaborate on a real killer fighter. The Air Ministry was notified of this and advised that under no circumstances would any official interference be tolerated. In November 1934, therefore, Mitchell began work on his Type 300 Fighter.

A month later, the Air Ministry commissioned Supermarine to produce an improved F7/30 design, from which point the project became government funded. On 3 January 1935, Supermarine confirmed this arrangement and provided details of their new machine. This specification included all the F7/30 requirements in addition to a tail wheel, as opposed to the more traditional skid, and wing-mounted machine-guns firing beyond the propeller arc. While this work was in progress, in April 1935 the Air Ministry redefined its requirement for the new Single-Engine Single-Seater Day and Night Fighter in F10/35. The main points were:

1. Had to be at least 40 mph faster than contemporary bombers at 15,000 feet.

2. Have a number of forward firing machine-guns that can produce the maximum hitting power possible in the shortest space of time available for one attack. The Air Ministry considered that eight guns should be provided.

3. Had to achieve the maximum possible and not less than 310 mph at 15,000 feet at maximum power with the highest speed possible between 5,000 and 15,000 feet.