To all those railway pioneers mentioned in the book.

They certainly started something!

And the world became a smaller place.

This electronic edition published 2013

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire

GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Ken Gibbs 2009, 2013

ISBN 9781445609188 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445624259 (e-BOOK)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

This book has been compiled from a number of magazine articles written by me over a number of years, making a miscellany of steam locomotive construction notes, tied together by additional relevant information, with reference to sights and operations from the workshops experienced in my apprentice years and subsequent practical knowledge gained in the works from 1944 to the end of official steam, and really beyond, as I am still working for several heritage railway groups. The photographs are from all sources acquired over many years, and selected for the book. Most modern photographs by the author.

As for the apprenticeship; I would do it all again!

Ken Gibbs

LCGI (M.Eng.)

INTRODUCTION

Lets have a quick look at the first real steam pioneers.

The first recorded person fascinated by Steam was Hero of Alexandria in 200 BC, who devised what could be called an embryonic steam turbine. This consisted of a hollow ball supported with two horizontal bearings, with two opposed bent spouts, looking like two arms of a swastika. Filled with water and heated, the steam generated exited through the spouts and rotated the ball. Really a curio and not exploited!

So while the world developed and settled down somewhat, hundreds of years went by while technology developed beyond the physical strength of man and horse. The extraction of minerals of various sorts from the earth had, by the seventeenth century, considerably developed. Mining techniques were among the technologies developed, and it was found that the deeper man dug into the earth, the more he was hampered by the essential to life itself, water.

The old saying Necessity is the mother of invention is still as true today as it has always been. Lifting water a short distance without pumping it or carrying it in buckets was assisted by the experiments of one Thomas Savery, who devised a system of forming a vacuum which sucked up water through a pipe, then having delivered it to a higher level chamber, delivered it to another higher level chamber by the pressure of steam on the water surface, forcing it up a delivery pipe. Savery also set up the worlds first steam engine (stationary) manufactory in London in 1702. His pump is described and illustrated in his work of the same date, titled The Miners Friend. While his pump was suitable for big houses, it would not work in mines. The Steam Age was opening up, continual improvement was inevitable, and 1705 saw the next important step.

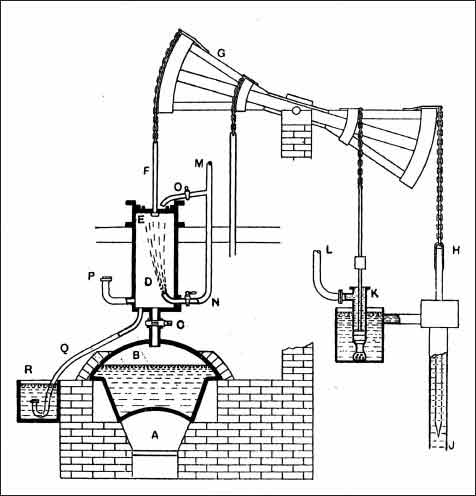

The improvements applied by Thomas Newcomen represented a great step forward. The illustration shows the beam, pump rods one end, steam cylinder the other. Steam entered the cylinder, a jet of cold water condensed the steam which had entered as the weight of the pump rod pulled the piston up to the cylinder top, and the atmospheric pressure forced the piston down, thus raising the pump rod. This system operated in mines for about sixty years, when a young James Watt started his model-making and experimenting. He noted the jet of cold water cooled the cylinder and left the walls of the cylinder wet. He considered this a waste of heat and thus the power of the steam. He devised a separate chamber where the steam could be condensed with the cold water, keeping the heat in the cylinder, making the operation more effective. Development continued.

Newcomens Atmospheric Engine. A: Boiler furnace; B: Steam boiler; C: Steam valve; D: Engine cylinder; E: Piston; F: Piston rod; G: Main beam; H: Heavy pump-rod; J: Mine pump; K: Pump for condensing water; L: Pipe leading to condensing water-tank; M: Condensing water pipe; N: Injection cock to cylinder; O: Water tap to top of piston; P: Relief or snifting valve; Q: Eduction pipe with no-return valve at end; R: Feed-water tank.

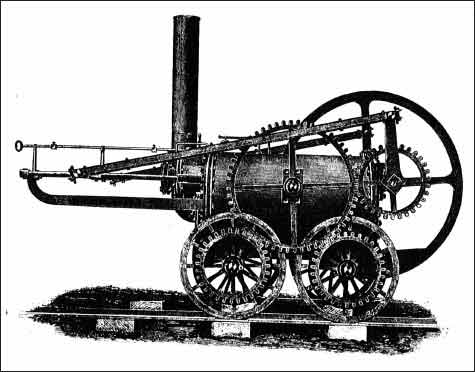

How the railway story began: the Pennydarren locomotive of Richard Trevithick, 1804.

So, steam, cylinders, rocking beams, static engines spreading over the countryside. But James Watt, double-acting steam, and no cold water spray changed all that!

It was inevitable that such a power source would find another application. So while theories were discussed, and models made, it was a Cornish man who decided on a mobile application in full size. Richard Trevithick decided to replace the limited power of man and horse with a mobile application of the principles of the static steam engine; thus 1804 saw the introduction of the steam locomotive to the mining and quarrying tram roads and plate ways. The power of man and horse had been overtaken!

1

EARLY LOCOMOTIVE DESIGN AND MANUFACTURE

Books on railway history, and the steam locomotive in particular, appear to always begin in one of two ways. They either start with the father-and-son combination of the Stephensons and their winning locomotive Rocket, or they begin with the Father of Railways, Richard Trevithick and his locomotive of 1804 for the Pennydarren tram road. In both cases, it was not the first venture of either of them into the world of steam power. Several others of the period soon followed on the heels of the 1804 Trevithick venture. Blenkinsop patented and Murray completed a two-cylinder (vertical) engine to run on a rack rail system in 1812. Blacket of Wylam Colliery followed with a smooth-wheel version made by Hedley in 1813. This was not successful but was rebuilt, emerging as Puffing Billy in 1813, reverting to two cylinders vertically operating a beam system. George Stephenson began building his first locomotive in 1814, made at the West Moor Workshops of Killingworth Colliery. This locomotive also had vertical cylinders and crossbeams, vertical rods working cranks and gear wheels to the smooth-wheel drivers. Steam was discharged as exhaust into the chimney, thus assisting the blast and keeping the fire glowing. In 1816, Stephenson produced a chain-driven locomotive for Killingworth. Up to about 1820, the emerging and developing steam locomotives had been employed solely for the purpose of achieving a replacement for the horse in moving around the product of the collieries, but thoughts of passenger traffic as well as goods were beginning to emerge.

A Bill submitted to Parliament was rejected three times but eventually was passed in 1821 and 27 September 1825 saw the first public railway in the world opened for traffic, with the