Contents

Acknowledgements

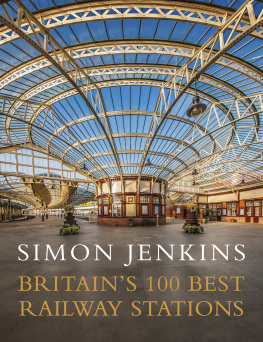

Sir John Betjeman features strongly in this book as it was time spent driving him round London in the 1970s that bred in me an early affection for stations (as for churches). His enthusiasm for these places and his eye for the charm of old buildings were infectious. He was almost in tears wandering through the near-derelict Broad Street. I would love to have known his hundred best, except that he would never have stopped at a hundred.

Since I have tended to ask everyone I met to suggest a best station, I cannot thank them all. Those whose help I particularly record are Marcus Binney, Simon Bradley, Ann Glen, Julian Glover, Chris Green, David Lewis, Bill McAlpine, Jeremy Musson, John Prideaux, Andy Savage, Peter Saxton and Tony Travers.

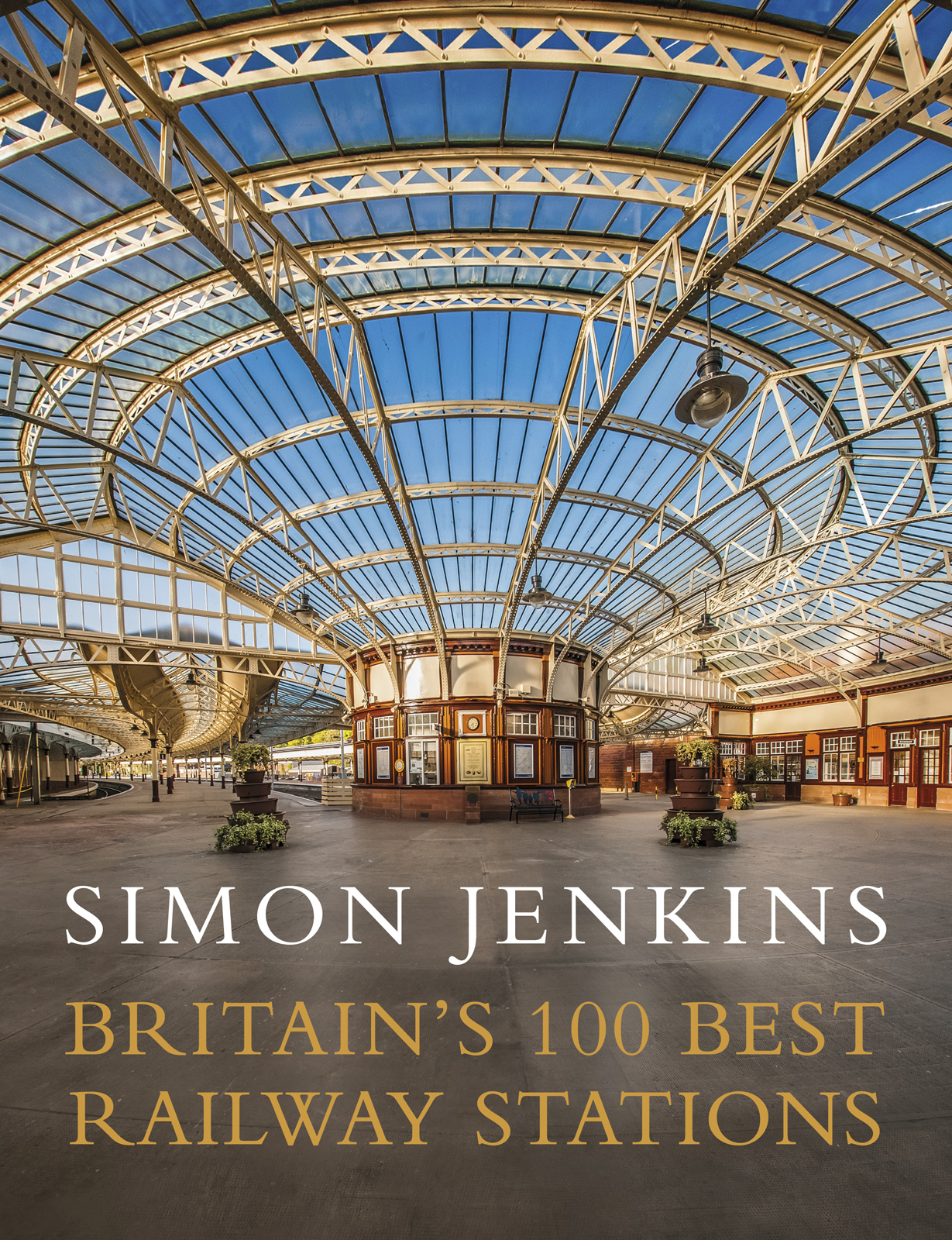

Special thanks go to colleagues at the body I founded in 1984, the Railway Heritage Trust, whose current director, Andy Savage, offered many vital corrections to the text, and whose photographer, Paul Childs, supplied many of the pictures. Paul is among the finest recorders of todays railway, in the tradition of the great John Gay. I also thank many others who have helped make this such an enjoyable book to write. They include the Penguin quartet of editor Daniel Crewe, picture researcher Cecilia Mackay, copy editor Jenny Dereham, and publicist Ruth Killick. Others involved were Keith Taylor, Claire Mason, Catriona Hillerton and Mike Davis.

ALSO BY SIMON JENKINS

A City at Risk

Landlords to London

Companion Guide to Outer London

The Battle for the Falklands (with Max Hastings)

Images of Hampstead

The Market for Glory

The Selling of Mary Davies

Accountable to None

Englands Thousand Best Churches

Englands Thousand Best Houses

Thatcher and Sons

Wales

A Short History of England

Englands 100 Best Views

Englands Cathedrals

Bibliography

Authors whose books I have used most heavily are listed below. I have not listed innumerable works on individual stations, nor can I list the hundreds of books that deal primarily with railways rather than stations.

Barman, Christian: An Introduction to Railway Architecture, 1950

Bennett, David: The Jubilee Line Extension, 2004

Betjeman, John, and John Gay: Londons Historic Railway Stations, 1978, 2001

Biddle, Gordon: Britains Historic Railway Buildings, 2003, rev. 2011

Great Railway Stations of Britain, 1986 Victorian Stations, 1973

with O. S. Nock: The Railway Heritage of Britain, 1983

Binney, Marcus: Great Railway Stations of Europe, 1984

and David Pearce (eds.): Railway Architecture, 1979

Bowers, Michael: Railway Styles in Building, 1975

Bowness, David, with Oliver Green and Sam Mullins: Underground, 2012

Bradley, Simon: The Railways, 2015

Crook, J. Mordaunt: The Dilemma of Style, 1987

Dow, Andrew: Dictionary of Railway Quotations, 2006

Fawcett, Bill: Railway Architecture, 2015

Freeman, Michael: Railways and the Victorian Imagination, 1999

Garnett, Andrew: Steel Wheels, 2005

Glancey, Jonathan: John Betjeman on Trains, 2006

Gourvish, Terry: British Rail 19741997, 2002

Jackson, Alan: Londons Termini, 1969

Judt, Tony, Glory of the Rails, New York Review of Books, 23.12.2010 and 13.1.2011

Kellett, John R.: The Impact of Railways on Victorian Cities, 1969

Legg, Stuart, ed: The Railway Book: An Anthology, 1988

Lloyd, Roger: The Fascination of Railways, 1951

Loudon, John Claudius: An Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture, 1833

Meeks, Carroll L. V.: The Railroad Station, 1956

Menear, Laurence: Londons Underground Stations, 1983

Minnis, John: Britains Lost Railways, 2011

Parissien, Steven: Station to Station, 1997

The English Railway Station, 2014

Richards, Jeffrey, and John M. Mackenzie: The Railway Station: a Social History, 2012

SAVE (ed. Marcus Binney): Off the Rails, 1977

Simmons, Jack: The Railways of Britain, 1986

The Victorian Railway, 1991

Wills, Dixe: Tiny Stations, 2014

Wolmar, Christian: The Subterranean Railway, 2004

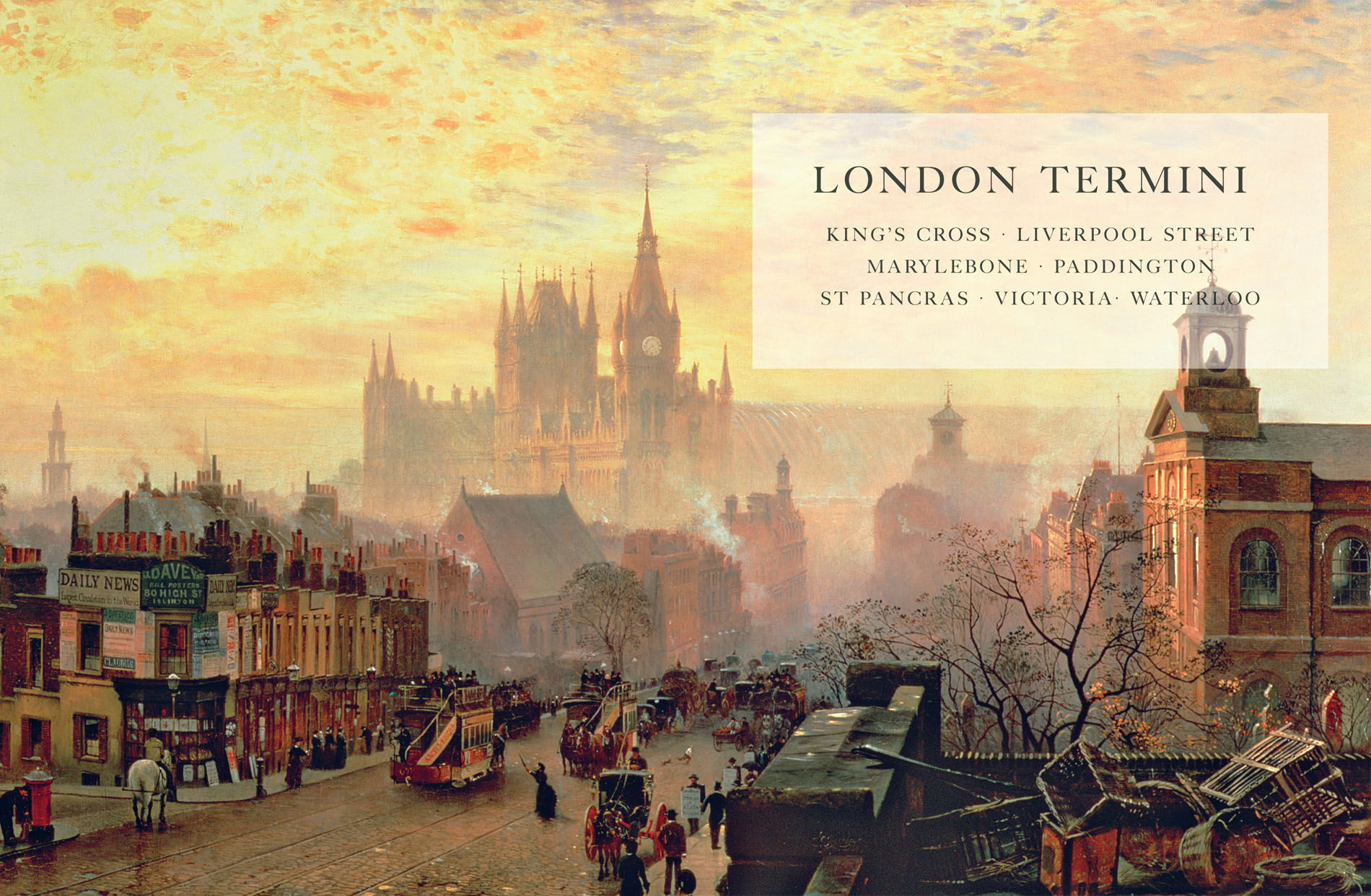

St Pancras from Pentonville by John OConnor, 1884

LONDON: THE TERMINI

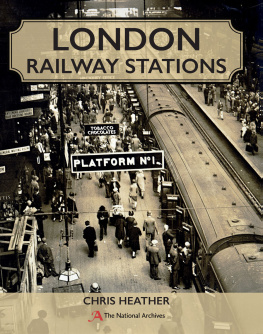

Central London was a repelling magnet to the railway. Neither government nor the rail lobby could overcome the hostility of the citys landed estates to tracks and termini jeopardising their rental values. As a result, the London termini were not the majestic hubs built in Paris, Berlin or Milan. Trains came to a in what were initially suburbs. The first versions of Paddington, Victoria, Waterloo and Liverpool Street were hundreds of yards short of their present locations. Only the railway companies crossing poorer land to the south and east were able to penetrate the City of London. Even then, none of the southern routes, with the exception of Holborn, could get beyond the north bank of the river. The result was that London had an astonishing fifteen termini.

The surface railway map of London is thus curiously lopsided. Termini from the north and west are ranged along the line of the Marylebone and Euston Roads. Termini from the south are along the line of the Thames, but the southern access lines are a cobweb of cross-cutting tracks, displaying how the early companies struggled to get as close as they could to their new markets. The result was a chaos of junctions, as at Borough Market and Clapham Junction. Trains to the south-east go from Victoria in the west, crossed by trains to the south-west from the more easterly Waterloo.

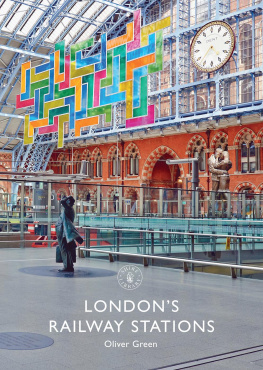

For the companies, the London termini were their showcases, although only Euston, Paddington and St Pancras were architecturally impressive. ) put most if not all the London termini under varying degrees of threat, although only Broad Street completely vanished. Saddest was Prime Minister Macmillans approved destruction of the original Euston, its replacement so miserable that it is now planned for demolition and rebuilding. But the recent revival has delivered gains, including the magnificent restoration of Kings Cross, Liverpool Street and, most spectacularly, St Pancras. I have omitted lesser London termini as insufficiently outstanding.

KINGS CROSS

*****

At the height of the competitive frenzy that consumed Londons railways in the 1860s, Kings Cross was plain Jane, the poor kid on the block. Built in 1852, it was overshadowed by neighbouring St Pancras, muscling on to its patch fifteen years later, the epitome of style and glamour. But that was the 19th century. Come the 20th, Kings Cross was suddenly the beautiful Cinderella and St Pancras the ugly sister. To have its roof expressed in the arches of its faade was honest. St Pancras was now a monstrosity, a ragbag of pseudo-historical references. When stations were lined up for execution at the time of the Devastation in the 1960s (see ), it was St Pancras that was condemned. Kings Cross, seen as a precursor of modernist virtue, was to be saved.