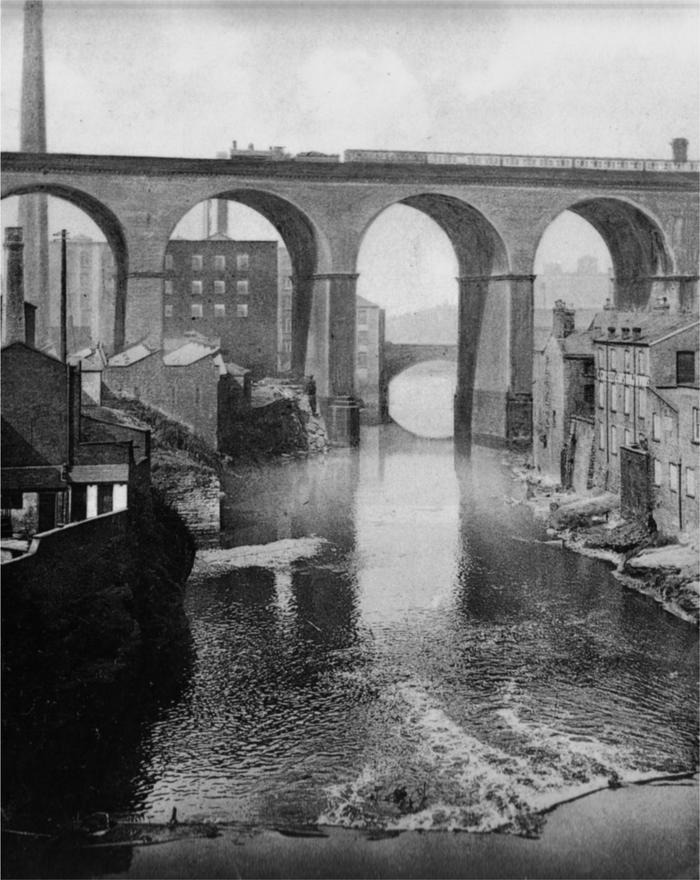

Stockport Viaduct. This view gives some idea how the viaduct over the Mersey Valley dominates the centre of Stockport.

C ommunication is a necessity for civilised societies. The earliest such societies were located in the valleys of great rivers such as the Nile and the Indus. The water of the rivers provided the means for irrigation and thereby the development of agriculture; they also provided the means of transport and communication for these early civilizations. The inhabitants of these societies learned how to use draught animals for agricultural purposes. However, they found what they had developed was threatened by barbarian enemies who, while not so advanced economically, had utilised the horse for the purposes of transport and particularly for warfare.

The speed of the horse, its relative intelligence and the ways in which it could be trained gave those who exploited it a huge advantage. It would not be unfair to say that, for a millennium and more, the horse was the key to economic, military and political power. The problem with the horse was the finite limits on its capacity and endurance. A horse could only go so fast, or a team of horses could only pull so heavy a load, or go at such a speed. A messenger could ride no faster from, say London to York in 1700, than his predecessor would have done in 1200. By the late eighteenth century, the then advanced world needed a new, more efficient and more powerful horse. This could only be a mechanical horse or, in that happy transatlantic phrase, an Iron Horse.

The invention of such a device was both a product of, and also a vital contributor to, that extraordinarily complex series of interacting processes which historians loosely but conveniently call the Industrial Revolution. This involved massive increases in humankinds control over nature, in the output and productivity of human labour and the scale and complexity of human co-operation and social organisation. The Industrial Revolution set in motion many of the economic and social processes which characterise the modern world, not least the expectation in the advanced economies that citizens have the right to enjoy a more or less continuous rise in their living standards and expectations.

The Industrial Revolution and associated technical and scientific developments in agriculture, as well as changes in landownership, meant that a hugely increased and predominantly urban population was supplied with food by a drastically reduced rural workforce. Those innumerable small towns and villages, each a centre of its immediate economic hinterland, that had been so characteristic of pre-industrial Britain, either stagnated or grew and transformed into centres of industry.

In the towns a radically new social fabric developed. Long-established social inter-relationships were destroyed. For example, the old semi-paternal nexus between squire and tenant, tenant farmer and labourer, priest and congregation, master and servant became anachronisms. Society was dominated by less personal relationships, such as those of employer and employee and producer and consumer. Most of all, the Industrial Revolution saw the emergence of the modern working class or proletariat; workers who sold their labour-power in exchange for wages, sometimes being employed in workforces of hundreds or thousands in factories and mills.

In finding their needs totally at odds with those of their employers, they learned from experience that the only way to defend and develop their interests was by collective industrial action. Workers self-help, especially in the form of trade unions, gave expression to this. The bringing together of huge numbers of impoverished or poor people in the industrial towns created public health, public order and other issues which could only be addressed by radical changes in social policy. With the improvement in communications and the overall rise in real wages, production increasingly was for national but also international markets. The British economy became embroiled in a tangle of worldwide commercial and financial business transactions: it was the beginning of globalisation.

All this amounted to a revolutionary change in almost every aspect of life. Although some parts of the process can be seen to have started developing momentum as far as back as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was in the eighteenth and especially the nineteenth centuries that the processes matured. If just one factor had to be identified as critical to industrialisation and all its associated changes, it would have to be the invention of reasonably efficient steam engines.

They provided the power for mechanised forms of industrial production and, after much further trial and error, were a prime mover in the field of transport. The latter was, of course, the steam locomotive. The quite

It is hard for us in the twenty-first century to appreciate the extent to which railways dominated land transport by the end of the nineteenth century. The statistics of their achievement are impressive. Between 1840 and 1870, annual passenger numbers rose from around 20 million to 336 million, and the amount of freight moved from 5 million to almost 170 million tons. Scarcely any town of any size was not served by one or more railway lines by 1900. The few towns that were never linked to the network either stagnated or actually declined even during the periods of sustained economic growth that made up much of the second half of the nineteenth century.

The railways also had a massive social, economic, intellectual and cultural impact. Processes of change from within and without are the dynamic of any society. The speed of change in Britain was enormously enhanced by the development of the railways. While some significant improvement to internal transport had been effected by turnpike roads and by canals, it was the railways that effectively shrank the British Isles, and made that which was previously distant, close. The first simple lines usually connected quarries and mines to the nearest navigable waterway, and little interest was expressed in the conveyance of passengers. The success of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in 1830 in benefiting the business communities of those cities was compounded when, to everyones surprise, it was found that there was also a demand for passenger travel, much of it just for pleasure.

The coming of the railways meant that a reasonably cheap form of transport was available throughout the land for moving minerals, raw materials and the products of industry. That was their prime purpose. The growth of significant business in moving people had not been foreseen and was a bonus. The very idea that people would travel in large numbers for pleasure would have seemed utterly ludicrous in 1700 when travel was relatively and absolutely slow, expensive, difficult and often dangerous. Within the next 150 years, however, large numbers of people, excluding all but the very poorest sections of society, were benefiting from the enormous broadening of horizons that much easier and cheaper travel brought.

The railways contributed enormously to economic and social change. They broke down rural isolation, they enabled labour and capital to be much more flexible and mobile, all factors essential for a modern industrialising economy, and they were part of the process of eroding family, local, district and national identities within Greater Britain. Railways undermined existing social and cultural practices. They greatly increased the speed with which ideas and information could be transmitted, and assisted the spread of the written word and of reading as an activity both with serious purposes in mind and just for simple pleasure.