GRAVESTONES

TOMBS AND

MEMORIALS

TREVOR YORKE

TREVOR YORKE

COUNTRYSIDE BOOKS

NEWBURY BERKSHIRE

First published 2010

Trevor Yorke 2010

All rights reserved. No reproduction permitted without the prior permission of the publisher:

COUNTRYSIDE BOOKS

3 Catherine Road

Newbury, Berkshire

To view our complete range of books, please visit us at

www.countrysidebooks.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 84674 202 6

Photographs and Illustrations by the author

Designed by Peter Davies, Nautilus Design

Produced through MRM Associates Ltd., Reading

Typeset by CJWT Solutions, St Helens

Printed by Information Press, Oxford

| Introduction |  |

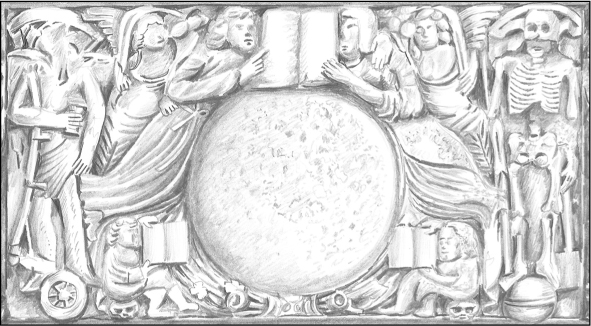

I am as guilty as anyone of assuming that old gravestones and tombs are no more than simple records of the deceased or collectively form a backdrop to the church. I had always thought they only mustered interest when massed together in the gloriously ostentatious Victorian cemeteries. It never crossed my mind to pay too much attention to them when visiting churches whilst researching for a recent book until, while leaning upon one such memorial to steady my camera as I photographed a small Gloucestershire edifice, I became aware that I was being stared at! Stepping back in surprise I found that I had made eye contact with a skull, and standing back further realised that he was not alone. In fact the tomb I had thought of as no more than a convenient tripod was crammed with carved skeletons, figures, books and tools surrounded by lavish decoration and with a central plaque which confirmed that this work of art was nearly 300 years old.

This Eureka moment inspired me to look at my local churchyard in a new light and although I had walked through it many times before, it was only now I noticed strange carvings, mysterious symbols and humorous effigies. Here beneath a cloak of trees and ivy were fine sculpture and elegant calligraphy, centuries of changing styles which had mostly been forgotten. It was also clear that there was a lot more information about the deceased than just a name and dates. The type of stone used, the quality and quantity of carving and the additional text all gave clues to the persons standing in society.

This book sets out not only to aid the family historian or church visitor by translating some of the mysterious symbols and text, but also to open our eyes to the works of art which stand free to view. It begins by explaining the development of the churchyard and cemetery and the changes to burial practices. The second and third chapters then look at the period styles of gravestones and tombs and the shapes and features which help date them. The last two chapters look in detail at the carvings and inscriptions, showing the variety and quality which can be found and their possible meaning.

Using my own drawings and photographs I hope to inspire the reader to take a closer look at the memorials in their local graveyard, and the sculpture and tragic tales carved upon them. Some may leave with a closer connection to the deceased, an appreciation of the skill of the mason and perhaps the feeling that life is not so bad today as we sometimes feel it is!

Trevor Yorke

FIG 0.1:Examples of the different types of memorials and some of their details which can be found in churchyards and cemeteries.

C HAPTER 1

| Churchyards and Cemeteries |  |

A Brief History of Burial

FIG 1.1:An imaginary churchyard with some of the memorials and features which can be found today after over a thousand years of burial. Such has been the displacement of soil over the centuries due to reburials building up on the same spot that many churches have a trench around them and retaining walls because the ground level has risen by up to a couple of metres!

I vy-clad gravestones and crumbling tombs illuminated by moonlight through a gloomy ceiling of trees with only the hoot of an owl to break the eerie silence. This familiar image of the churchyard was first eulogised by poets in the 18th century, then became a vital component in the Gothic novels of the early 1800s before being crystallised in our minds by 20th-century horror films. Yet this spooky incantation seems far removed from the neatly-trimmed landscaped sites we see today and, as you will discover, was quite different from that which preceded it. Before looking in detail at the memorials found within, it is worth explaining how churchyards have been transformed over the years, why cemeteries were founded and what features you can still find there.

The earliest forms of burial we can readily see in the landscape today are the various types of earthen mounds and stone chambers erected from the Neolithic Age up to as late as the Early Saxon period to house either a corpse or cremated remains. Archaeologists regularly uncover cemeteries which can date from the second half of the Bronze Age through the Roman period (where they were usually sited outside of town boundaries) and into the Dark Ages. One key feature they look for to help date the graves is their alignment where they are laid out in no set direction it implies a pagan burial but where they are on a roughly east-west axis the deceased was probably a Christian. This can usually be tied in with when the Saxons in a region were converted by missionaries the armies of Celtic priests and monks invading from the north and those of the Roman Church from the south during the late 6th and 7th centuries.

Christian burials

Christian burials

Christians are buried with the head at the west end of the grave facing up and the feet at the east end. It is generally said that this is so the dead will awake at the Second Coming of Christ and be able to face in the direction from which He will arrive. However, the practice of burial so the deceased can look at the rising sun predates Christianity and it is more likely to be a hangover from older religious beliefs. The bodies of most people through the Middle Ages, and the poor up until the 19th century, would have been interred in a shroud, tied above the head and feet; only the better off would usually have a coffin.

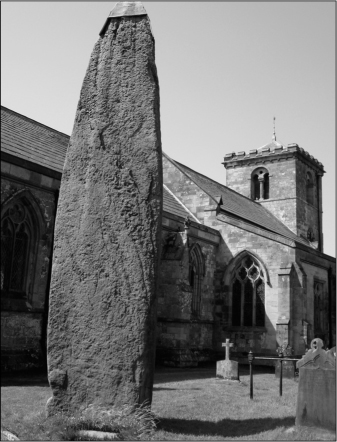

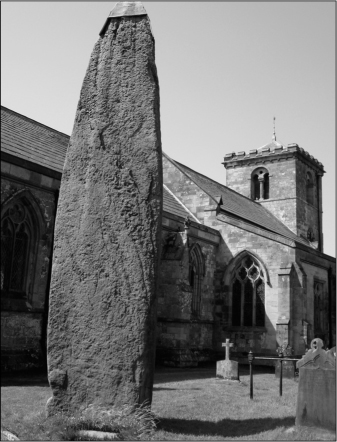

FIG 1.2: RUDSTON, YORKS:The success of Christianity partly lay in the way the early Church adopted old pagan beliefs rather than destroying them. Many churchyards were established around existing religious sites, and some today retain a distinctive round or irregular plan which implies they were pre-Christian. Others contain ancient features like round barrows or standing stones, none more notable than this huge monolith at Rudston. Pagan symbols like this may have simply had a cross cut into them to drive out old spirits.

TREVOR YORKE

TREVOR YORKE

Christian burials

Christian burials