All rights reserved. No reproduction permitted

without the prior permission of the publisher:

Photograph of Gallipoli trench on by Steve Jacques.

With many thanks to Michael Bode for his assistance in compiling this book.

Maps and illustrations by the author.

This dignified building of remembrance is dedicated to those British and Commonwealth soldiers who were killed in action locally and who have no known grave. It was built by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and unveiled in 1927. Ypres was of strategic importance during the First World War and no fewer than five major battles were fought around it. By the end of the fighting the town was a ruined shell and the allies had lost some 300,000 men in the Ypres Salient. The bodies of 90,000 of these were never recovered. German losses around Ypres during the war are thought to be around 200,000. Every evening at 8 pm the road through the gate is closed and buglers from the towns fire brigade sound the Last Post.

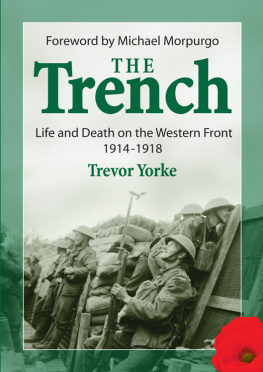

The picture opposite is of the Menin Gate at Ypres in Belgium. The caption speaks for itself. Ypres is a sad town but an enormously positive one. Its one of the places that has grown out of its wartime ruins. I find it very moving that its inhabitants have taken the time and the trouble, and have had the spirit to rebuild their town, which was largely destroyed in the Great War. In my mind, it symbolises hope.

Ypres isnt the sort of place you go simply to enjoy yourself. You go for the experience and I think all young people should visit the town and its surrounding cemeteries. You must also visit the excellent In Flanders Fields museum there, which is one of the best museums about the Great War that Ive ever visited. It doesnt seek to glorify the war in any way, it just tells it as it was - and Id urge any visitor to the town to go there and perhaps take along the children (if theyre old enough), in order to give them a better understanding of this most terrible of conflicts.

I always also visit at least one of the wartime cemeteries outside Ypres. Indeed, I came across the name of a Private Peaceful at one such cemetery, and it was that which inspired my book of the same name.

When I came to write War Horse, I decided I would tell the story of that war seen through the eyes of a horse. Joey, I would call him. It would be an English story, but a German one too, and a French one. It would be a tale, as far as possible, of the universal suffering, not just in that war, but in all wars, and on all sides. That is the spirit in which the book was written, and in which the play is acted out now each night, not only in London and in the US, but also now in Berlin.

To tell the story is the only way we have left to remember, and the only way to pass it on. And it is important to pass it on, important for the men who died on all sides, all now unknown soldiers, for those who suffered long afterwards and grieved all their lives. And important for us too. If they gave their todays for our tomorrows, then, I am sure, after all they went through, and died for, they would wish to see us doing all we can to create a world of peace and goodwill, a world that one day will turn its back on war for good. It is through their words and our stories that we must and will remember this and remember them. Then we really will be honouring their memory.

In 2014, as we begin to mark the centenary of the First World War, we should honour those who died, most certainly, and gratefully too, but we should never glorify. We should heed the words of those who were there, who did the fighting, and some of them the dying. To Wilfred Owen, the words Horace had used to glorify war centuries before, Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori - how sweet and fitting it is to die for your country - were simply the old lie.

During these next four years of commemoration we should read the poems, the stories, the history, the diaries, visit the cemeteries - German cemeteries as well as ours - they were all sons and brothers and lovers and husbands and fathers too.

There should be no flag waving, unless it be the lowering of the flags of all the nations who lost their sons, unless it be to celebrate the peace we now share together, unless it be to reaffirm again our determination to guard our freedom, but as far as humanly possible to do it in peace. And when we sing the anthems, let them be anthems of peace and reconciliation.

Come each November over the next four years, let the red poppy and the white poppy be worn together to honour those who died, to keep our faith with them, to make of this world a place where freedom and peace can reign together.

Michael Morpurgo

Sepia photos of uniformed relatives in family albums; silent images from old newsreels of soldiers trudging through muddy trenches, and pictures of field artillery on wooden gun carriages, can make the First World War seem distant and irrelevant in the modern world. Current media has given a verdict that the war was run by pompous generals with outrageous moustaches and a nonchalant disrespect for life as they sent thousands of trusting soldiers to a casual oblivion. The scale of the conflict and the suffering it produced is frightening not only because of those lost on the front lines but through the millions of men, women and animals who also suffered in what seems a largely pointless war.

At the time however, the First World War appeared new and challenging. Rapid developments in weaponry, armoured vehicles, aircraft, chemical warfare and defensive measures pushed designers and industrialists to the limits. Military planners and officers in the field were constantly revising tactics and devising new ways of coordinating their forces. Politicians and commanders had to try and predict the enemys next move while juggling their colossal fighting machines over the numerous fronts of the wide empires they controlled. The decisions made by these same leaders in the period immediately after the war ended has not only created conflict and tensions which are still felt today, but also began an irrevocable change in the world from one of monarchy and empire to democracy and independence.

Despite the global aspect of the First World War (and the war was indeed global in that few countries in the world were not impacted in some way by it) this book concentrates upon what became known as the Western Front, where Germans became locked in combat with French, Belgian, British, and British Empire forces along a huge 450 mile complex of trenches. These were the killing fields between 1914 and 1918.