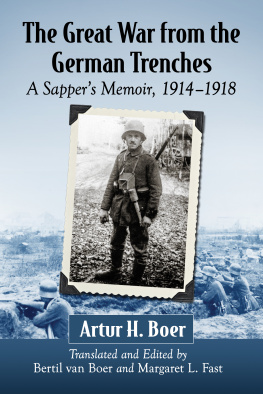

Artur Hermann Boer (18931967) in 1965 (courtesy van Boer family archives).

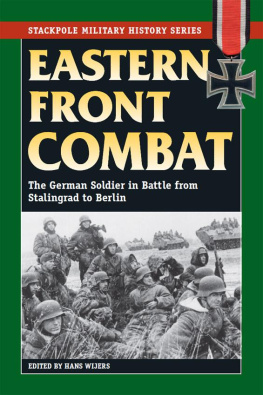

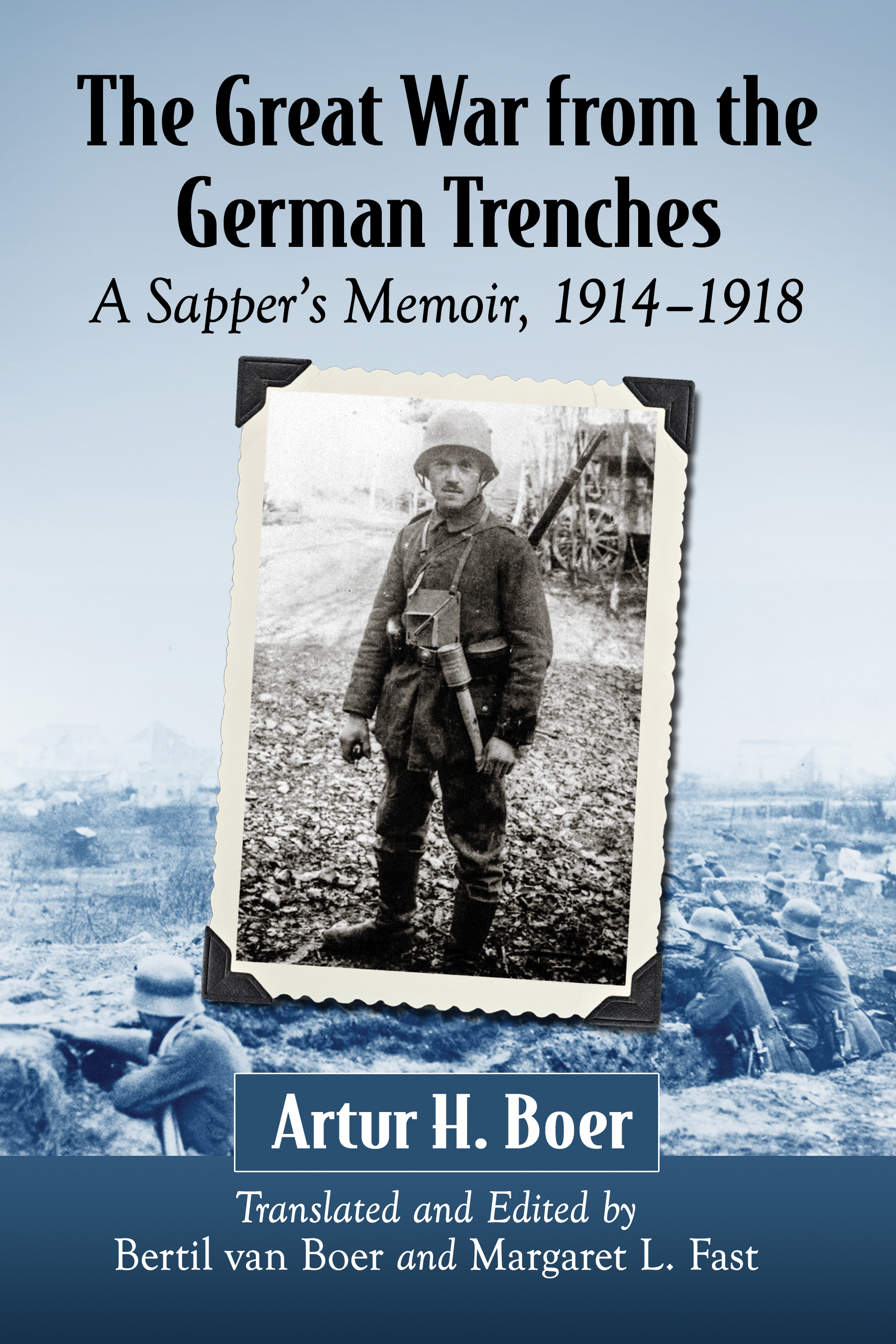

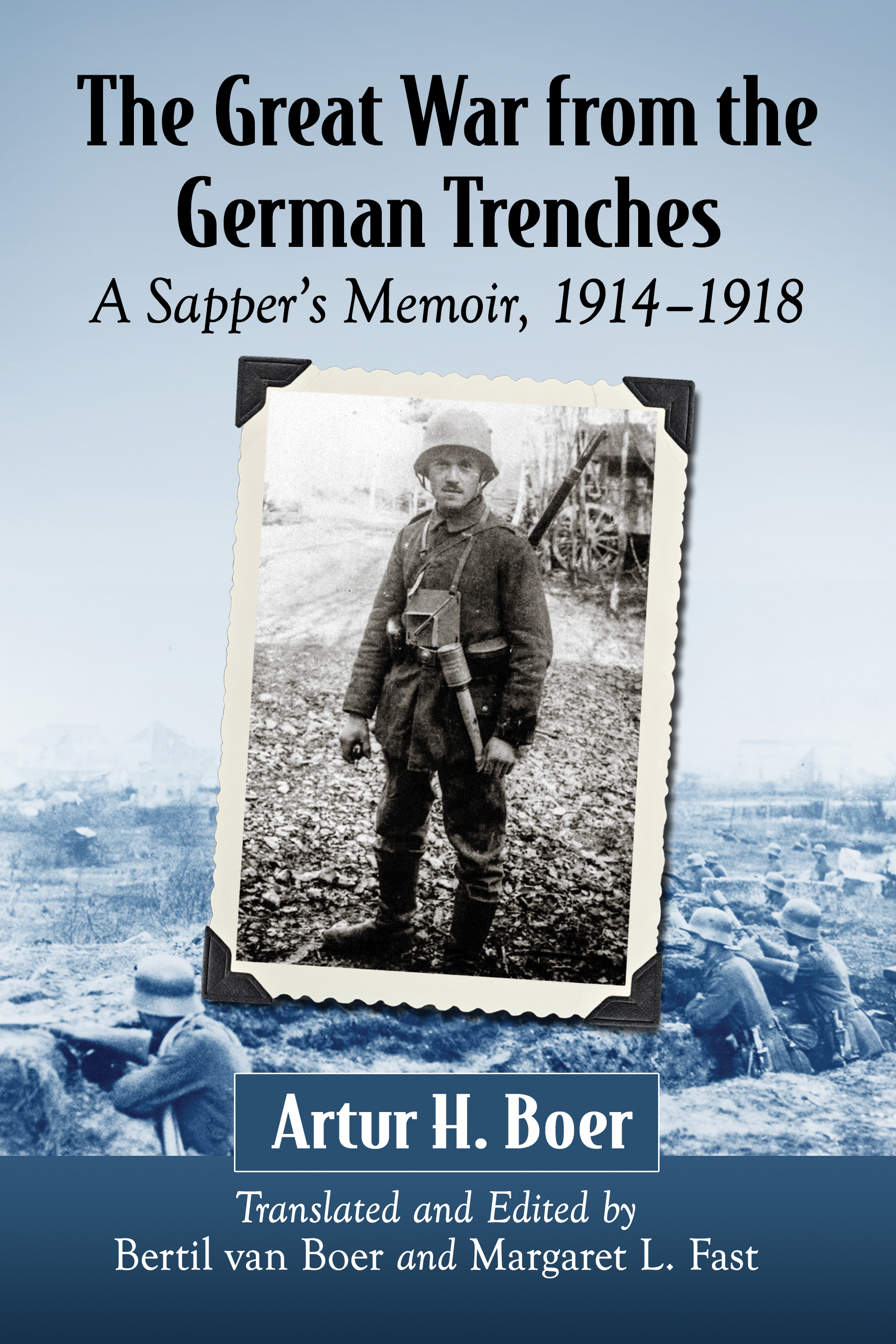

THE GREAT WAR FROM THE GERMAN TRENCHES

A Sappers Memoir, 19141918

Artur H. Boer

Translated and edited by Bertil van Boer and Margaret L. Fast

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2392-4

2016 Bertil H. van Boer and Margaret L. Fast. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Artur Boer at the front in uniform in 1915 (family archives); German soldiers in a trench between 1914 and 1918 (Library of Congress)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To the memory of

Arturs eldest son,

Alf Bertil Herman van Boer

(19242014)

Foreword

by Hans Boer

The First World War (19141918) lies a century behind us, but like the Second World War should never be forgotten; the events from the beginning of our previous century deserve to be included in our memories. Of course, the methods of waging war were not as consciously grim as in the wars of later times, but nonetheless were the cause of enormous suffering and tragedy. Millions of families were split apart, children lost their fathers and wives their husbands, and a huge number of people were lost. Just like the Second World War, the First World War altered peoples picture of the world at large, and as in all wars apparently meaningless events were actually important to understanding the realities of war. For the little man, for you and me, these realities of war are unfathomable and incomprehensible. Chronicles of war that we usually read are often reconstructed, dramatized, and romanticized. Often the horrors are described for the sake of the horror itself and to provide an approximation of the violence and blood. The present book, without excuse or exaggeration, documents the everyday aspects of war. It is the memoir and reflections from the trenches and battlefield of a frontline soldier during a particularly bloody epoch. This book gives us the occasion to place ourselves directly into the action, as seen from a sappers perspective.

Artur H. Boer (18931967), my father and the author of this book, moved after the end of the war from Germany to Sweden, where he lived in Kumla and Karlskoga, among other places. His experiences during the war left deep scars in his soul, and like the majority who have survived war up close, his eyes spoke of his experiences. For him, this book was a means of organizing his memories, and thus with it he has provided a worthwhile addition to the literature of the First World War.

As can be seen in several passages in the book, he was a lover of music, and in both Kumla and Karlskoga he played viola in the local orchestras. Otherwise, he worked in a shoe factory in Kumla and in Karlskoga at Bofors up to his retirement. In 1960, when he was pensioned, he began to write down his memoirs, and they remained unpublished apart from excerpts in the local Karlskoga newspaper, Nerikes Allehanda, in 1965. These memoirs are what you hold in your hands.

Let all of us, without reservation, concur with the ardent wish of my father that introduces this bookNo war ever againa valid sentiment to this day.

Introduction by the Editors

About the Book

BY BERTIL H. VAN BOER

I knew my grandfather. Such a statement ought to seem rather obvious, but for me it entailed a cross-cultural story that transcended nations and continents. I was born and raised in the United States, some five years or so after my father emigrated from Sweden. As a child, I knew little about my grandfather still back in the Old World (and nothing about my paternal grandmother, which is another story entirely), and it was not until I was twelve years old that we traveled to Europe and I met him for the first time. We were immediately drawn to each other, although we could not communicate in a normal fashion; at that time I spoke virtually no German or Swedish, and he knew only a few fleeting words of English, but my uncle Hans and my aunt Ulla, who spoke English quite well, acted as translators, as did my father. This made no difference to my grandfather, for he doted on my brother and me for the two weeks we spent in the town of Karlskoga where he lived. I played violin with and for him, learned some words and phrases in both his languages, and after we left, corresponded with him for several years until his death in 1967. In his letters, even in his seventies, he learned to write in English, after a fashion, and by that time I was becoming adept at German (the Swedish did not come until long after he died). These letters were about everyday life, and I later learned that he always awaited them with great anticipation.

I did not know until later that he too had been an immigrant. He was born in the Prussian town of Jarotschin (Jarocin in todays Poland) in 1893. His fathermy great-grandfatherwas an engineer for the Royal Prussian State Railways and his mothermy great-grandmother, born Klara Klugecame from a prominent Prussian family outside of Posen, then likewise a city in Prussia. I know little of his early life, save that he lost his mother earlyhow or why still remains a mystery to be solvedbut that he was raised to some degree by his stepmother, Lina Springer, who my great-grandfather had married after his divorce from his first wife. In this second family, he also had a half-sister, Martel, who he adored (and who I later also met in Mainz as a child, but she does not come into this story). Artur was well-trained as an engineer in Berlin at the Royal Academy of Engineering, as well as becoming a proficient violinist by taking instruction at the Royal Prussian Academy of Music. He was apparently incredibly gifted as a musician (eventually preferring the viola over the violin), but when he pressed to make it his career, the story goes that his father, a rather staunch and severe man, took his violin and smashed it over his knee, telling him in essence that this was no fit occupation for a productive human being. Or at least, that is the story I heard as a child. When he was recruited into the German army as one of the Pioneer Corps in 1914, he had already settled upon engineering as his occupation, having shortly before received his diploma from the Royal Academy of Engineering. He never lost his deep love for music, however, and even during the war continued to perform.

By the end of the war, having been wounded and gassed, he was disillusioned with both politics and war, and his return home to a distressed Berlin brought the futility of everything connected with World War I into focus. By 1920 he had enough of the depression and inflation that wracked his homeland and immigrated to Sweden. There he re-established his life, where he married my grandmother, Elsa Linnea Orest, in Karlskoga in 1922 and began work as a civil engineer. His life there, however, was not entirely calm, even though he continued to play his violin in the local orchestras and worked successfully for several firms, ironically enough including Bofors, one of the worlds leading manufacturers of weapons produced by a nation that has remained neutral in two world wars. Just as history repeats itself, so did his own life story; he divorced my grandmother and sent my father off into the military at the age of 13 (where he too was trained as an engineer/architect and as a musician, this time as a flautist and conductor in the latter fieldagain, another tale). He remarried, had another family (my aunt, uncle, and a flock of wonderful cousins), and because Sweden was neutral during World War II, in his new home he was able to escape the devastation that occurred in the rest of Europe. This meant a comfortable, if staid, life in central Sweden in a house that he himself designed and built, and later in an apartment as he grew older and had health problems.

Next page