Helion & Company Limited

26 Willow Road

Solihull

West Midlands

B91 1UE

England

Tel. 0121 705 3393

Fax 0121 711 4075

Email: info@helion.co.uk

Website: http://www.helion.co.uk

Published by Helion & Company 2011

Designed and typeset by Farr out Publications, Wokingham, Berkshire

Cover designed by Farr out Publications, Wokingham, Berkshire

Printed by Gutenberg Press Limited, Tarxien, Malta

Text and diagrams Leon Bennett 2011

Photographs as individually credited.

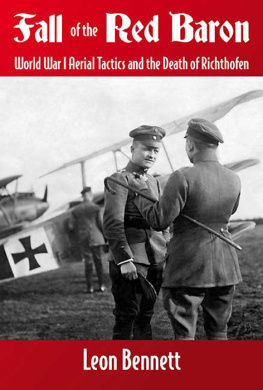

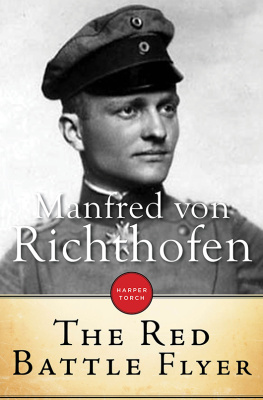

Front cover: Rittmeister Manfred von Richthofen standing in front of an iconic Fokker Dr.I

Triplane (Ullstein Bilderdienst).

Rear cover: Boelckes Swarm a loose group of roughly half a dozen Albatros fighters was typical of Hauptmann Oswald Boelckes 1916 approach (Flugsport, June 1917, p.373).

ISBN 978 1 906033 92 7

ISBN 978 1 908916 43 3 (eBook)

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written consent of Helion & Company Limited.

For details of other military history titles published by Helion & Company Limited contact the above address, or visit our website: http://www.helion.co.uk.

We always welcome receiving book proposals from prospective authors. We are particularly keen to hear from authors interested in publishing First World War aviation titles with us please contact us with your book proposal or for details of titles we are actively seeking to commission.

Contents

The publishers and author are aware that not all of the images in this book are of perfect quality. Nevertheless, we have chosen to include them as many are very rare, having seldom if ever appeared in print for nearly a century.

Performance: British Fighting Aircraft 19141917

Trend Lines Only

T he path of creation is never clear. In this instance, youthful enthusiasm plus the wonders of model airplanes played a part. Adult immersion in aero engineering and ballistics research came next, a process leading to familiarity with key British sources at the IWM (Imperial War Museum) and TNA (The National Archives). It is their vaults that currently hold the world of Red Baron raw data. Given the files, an understanding of the contradictory literature surrounding Richthofen and his achievements became possible. It was only necessary to nail it down.

Through all, my ever-patient wife R. made the book possible by assuming far more than her share of the ancillary chores. Her ability to translate both French and German made for comprehension of otherwise hopeless memos. In her hands, even loony software instructions were turned into clear English, resulting in the text you now hold.

S hooting down enemy aircraft was an important achievement in WWI. Success was vital to the infantry, serving to stop frontline strafing, and prevent observation by the enemy. Convinced of the need, every Air Service struggled for maximum combat success. Much effort went into locating the source of a pilots air fighting ability. To some it seemed a personal knackrather like hitting a curve balla skill beyond training or even logical description. One either had it or one did not. How were those gifted few to be identified? Was it all a matter of the right genes? An early display of brilliance?

Turning to the most successful of all, Manfred von Richthofen, (the Red Baron) we anticipate quick learning, and the natural combat skills of a born hunter. Instead, we find a mediocre student pilot and a poor shot, unable to hit the target with an airborne machine gun. Lacking any feeling for aerobatics, he opted for sullen denial, disparaging loops as useless stunts.

We sense the man as lacking in important skills, despite the right sort of ancestors, properly military. Given so hapless a start, we uneasily anticipate his end, and a quick end at that. Yet, it was not so.

Richthofen had another side, one that was all-important: the ability to reason and change his mind as circumstances altered. For example, early in the war, speed seemed critical to Richthofen and the Albatros series of fighters supplied that speed. Later in the war, he traded speed away for the extra maneuverability granted him in the form of the Fokker Triplane. His tactics changed accordingly.

He was that rare pilot with a grasp of the relationship between design and tactics. If he could dive away from trouble, diving had virtue as a tactic. However, if his machine had little to offer as a diver, with enemy aircraft easily out-speeding his airplane in descent, then no tactic was more stupid than evasion by diving. In short, tactics did not stand alone. Much had to do with the nature of his machine, as compared to the enemys.

Granted the importance of tactics in winning or losing, other factors were also important. How did tactics rank? After much combat experience, Canadian ace Billy Bishop The important thing was to use ones head. Guile and stealth were vital; bravado was so much nonsense. In his estimation, flying skill itself deserved third, or last place.

Even as we sense the self-preserving wisdom underlying Bishops conclusions, there came a severe criticism of Richthofen for employing that same level of caution; this given by Captain A. Roy Brown, an ace credited by many with the downing of the Red Baron himself. In Browns view, Richthofen sought mainly easy victims: He picked off lame ducks pulling [away] from a fight. He specialized in swooping on slow-motion artillery planes.

Whether the accusation was true or not, the tone of condemnation was clear. We sense a demand that acceptable tactics embrace more than the limitations of ones aircraft and skill they must pass muster as properly heroic.

To some extent, this burden of selflessness derived from the demands of strategy. The British were convinced that an offensive outlook was crucial to the production of ultimate victory. In practice this meant that every British airplane in good repair was to fight nearby enemy machines, no matter what the circumstances, and without concern for immediate victory. This approach was precisely the opposite of Bishops. As a tactic always fight amounted to an anti-tactic; one ignoring immediate prospects in the hope of achieving a long-term goal: the exhaustion of the enemy under the blows of an overwhelming number of British, French , Italian and American flyers. Ignored was a bitter truth: to join combat in the wrong circumstances meant only a suicidal sacrifice.

To Richthofen a certain nobility of tactics was important. One must not pretend to be wounded in order to lure an unsuspecting enemy to his doom. At the same time always fight was judged to be stupid, for only a fool could ignore the plain lessons and odds of combat. As Richthofen well understood, there are times when it is best to flee rather than fight.

This book is concerned with tactics; especially those tactics used by the Red Baron and his opponents. We open by freshly considering the means of Richthofens death. Competing claimants are examined in terms in terms of logic, rather than the usual contradictory eyewitness reports. Ground anti-aircraft fire is examined in terms of hit probability. Richthofens crossing of the frontlines on the fatal day, and the most dangerous altitude for doing so are developed. His attackers chances are viewed by means of machine gun scatter studies. We conclude by rating the possibility of Richthofens death by rifleman as quite possible; certainly as likely as any of the more celebrated possibilities.

Next page