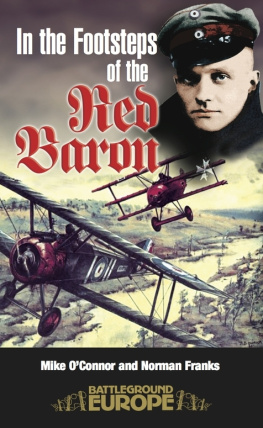

The well-known portrait of Manfred von Richthofen which found a place in many German living rooms of the time. He was the ace of aces. No other pilot approached his eighty confirmed aerial victories even though he himself fell in April 1918. The assessments of him differ. For many, even on the British side, he is an idol. On the other hand, others see him as an ice-cold killer and the Nazi prototype.

Death Was Their Co-Pilot

Aces of the Skies

Michael Drflinger

Translated by Geoffrey Brooks

Originally published in 2014 by

GeraMond Verlag GmbH, Mnchen, as Der Tod fliegt mit

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN AND SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street, Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Michael Drflinger, 2017

ISBN 978 1 47385 928 9

eISBN 978 1 47385 930 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47385 929 6

The right of Michael Drflinger to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

The first aircraft used in the First World War were more dangerous for the pilot than his adversary. That would change quickly as the war went on. Ernst Udet, the best of the surviving German aces, was still flying operationally in old monoplanes in 1916.

INTRODUCTION

The Beginnings of Military Aviation

Most inventors of flying machines are thinking of nothing but their military application! On the other hand the dreamers assure us that the appearance of the aeroplane will put a stop to war.

(Ferdinand Ferber, pioneer aviator, fatal crash, 1909.)

Flying was a dream of freedom since the time of Icarus. To lift off, fly over walls, shake off the restraints of gravity. Flying also meant imagination and fantasy. The poet rode his flying white horse Pegasus through the air; the dull, hard-working peasant was stuck to the soil. At the beginning of the twentieth century, flying was no longer a dream but reality. Yet even before the first flight over a reasonable stretch had succeeded, the strategists of power were already in the starting blocks painting bombing raids or violent aerial battles.

One of the military maxims of Wilhelm IIs Kaiser-Reich was to have great, rather rigid but very effective Enormous Things to do a splendid job. The Imperial Navy had powerful battleships instead of a fleet of cruisers to roam the seas. The artillery had especially huge guns for important functions. Therefore it came as no surprise when such a massive machine wearing the Iron Cross should appear in the skies.

In the earliest days of aviation the German Reich had decided on dirigible airships, other countries favoured aircraft from the outset. Undoubtedly one of the reasons for this was the absence of personalities advocating aircraft so strongly as a Graf Zeppelin or a Parsifal did airships, and the presence of a Kaiser so heavily favouring the airship development.

Especially in France, which despite the Wright Brothers must count as the real cradle of aviation, enthusiasm for flying grew into a mass phenomenon at the beginning of the twentieth century. Pioneers from all continents met in Paris to take the measure of other designers and pilots. Older readers may perhaps recall the series Die Grashpfer (The Grasshopper) in which these first years of flying were retold so intensely. What was not tried out!

From early on loud voices could be heard saying that aviation would play a significant role in a future conflict. In Germany it was Chief of the General Staff Helmuth von Moltke, later to become famous for the lost Battle of the Marne. In France, Capitaine Ferber was not only the master spirit of civilian aviation, but also had precise ideas of what duels in the air would look like. His book LAviation, ses dbuts, son dveloppement was published in 1908. He did not live to see how his prophecies turned out, for in 1909 he was killed when his aircraft crashed.

Led by General Hirschauer, with adequate State funding and a wellsupported aircraft industry, the French built up a well organised aerial corps.

The United States lost no time either. Pioneers such as the Wright and Curtiss brothers had little difficulty in convincing the Army of the advantages of the aeroplane, and new machines were purchased at once, although not in large numbers. It has to be said that these early aircraft can have had no real value for the military, but it was remarkable that the decisive Army authorities did understand the possibilities of aircraft. Not being faced with a threat of which advantage could be taken to test the modern technology, however, no Flying Corps was formed, and even after their entry into the First World War, the Americans lacked any aerial potential and were obliged to purchase aircraft in large numbers from the French.

The British had set up the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in 1912, the Royal Naval Air Service (officially in 1914), together with the Royal Aircraft Factory. Most of Great Britains military budget went into strengthening the Royal Navy, and so at the outbreak of war the British Empire had only 48 machines. An icy relationship existed between the naval fliers and the RFC. The armaments effort had increased towards 1914 but without approaching the French level.

At the outbreak of war, France was the leading world power in aircraft with 165 modern operational machines. Germany had made strong efforts to catch up in 1913, having got over her fixation with airships. Austro-Hungary had a few of the Taube type but lacked pilots as the budget was too small. The Russians were well equipped as regards numbers, but most of what they had were obsolete and barely fit for the Front.

In the first weeks of the war opposing pilots were still waving to each other. Here in the air the war was still chivalrous. That would soon change. On 5 October 1914 the two-seater biplane Voisin III No.89 took off, piloted by Sergeant Joseph Frantz with Observer Mechanic Corporal Louis Qunault, both members of Escadrille V.24. Frantz had flown pre-war and had won a number of air races for money. The Voisin III had a pusher airscrew and this did not interfere with the Hotchkiss machine gun manned by Qunault in the forward seat. Suddenly the French aircraft came across a German Aviatik B.1 of Feldflieger-Abteilung 18 piloted by Sergeant Wilhelm Schlichting with Lt. Fritz von Zangen as observer. Qunault seized his machine gun, aimed it at the Aviatik and fired. The weapon jammed after the 47th round, but by then the German machine had been mortally hit and crashed. The first ever aerial battle had been decided.