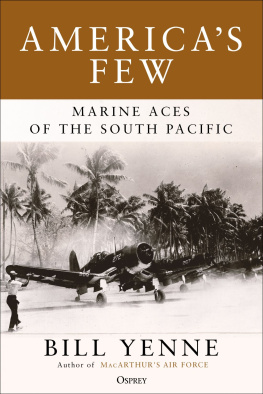

Images of War

GREAT WAR FIGHTER ACES 1916-1918

Norman Franks

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

P EN & S WORD A VIATION

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley,

South Yorkshire,

S70 2AS

Copyright Norman Franks, 2017.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 47386 126 8

eISBN 978 1 47386 128 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47386 127 5

The right of Norman Franks to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Photographs

As in the first part of this coverage of the aces of the First World War, photograph images have come from many people and many sources over my fifty years of study of First World War flying. Many came from the collections of the pilots themselves, many of whom I had the privilege to either meet or correspond with. Sadly they are now all gone.

Over the years I have co-operated and shared images with a number of friends who also study this period, some of them fellow authors. Some of them too have now departed. The main contributors therefore are, or have been: Greg van Wyngarden, Andy Thomas, Trevor Henshaw, Stuart Leslie, Tony Mellor-Ellis, Walter Pieters, and the late Mike OConnor, Chaz Bowyer, Frank Cheesman, Ed Ferko, Neil OConnor, Frank Bailey, Les Rogers and Hal Giblin.

Chapter 1

The Air War Becomes More Serious

In the first part of this two-part series, covering 1914-1916, we ended 1916 as the massive Somme offensive had finally petered out and the German fighter force had established their Jagdstaffeln . It will be remembered that in the initial stages of the First World War fighter aeroplanes such as the Fokker Eindeckers, had been distributed in twos and threes amongst the two-seat observation and bombing abteilungen , for protection. In between such protection sorties, the more aggressive young pilots had flown their fast little scouts to engage Allied machines that were either ranging artillery fire over the front lines, or flying into German-held territory to observe or bomb.

Two of these pilots had been Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann, and both had been the first airmen to receive the coveted Orden Pour le Mrite , Germanys highest bravery award. Immelmann had been killed in June 1916 and Boelcke in October, but Boelcke had persuaded higher authority to gather the fighters into a number of single units Jagdstaffeln shortened to the word Jasta.

By this time there were dozens of eager young pilots clambering to become Jasta pilots, and emulate the achievements of men such as Boelcke, Immelmann, Wintgens and Berthold . They also sought the recognition these early aces had achieved, as well as high awards from the various German states who all seemed compelled to lavish medals and orders on these new heroes of the skies.

It was not, however, any form of guarantee of a long life, and many of the early aces had already fallen. By January 1917 the three living top-scoring aces were Rittmeister Manfred von Richthofen with eighteen victories, Leutnant Wilhelm Frankl, with fourteen and Leutnant Walter Hhndorf with twelve. The winter weather had curtailed aerial activity to some extent, but the spring was coming, and the Jasta pilots were waiting.

On the British side, the DH.2 and FE.8 pusher-type fighters that had helped overcome the Fokker menace were about to be phased out, replaced by tractorengined machines, there being no need to have engines behind the pilot now that interrupter gears had been invented. The poor BE.12s too were ordered away from the front by no less a personage than General Hugh Trenchard, head of the RFC. December 1916 saw the first Sopwith Pups arrive in France, nimble little single-seat fighters with a single Vickers gun firing through the propeller, and in January 1917 came a newer type of fighting reconnaissance aeroplane, another Sopwith design, the unusually named 1 Strutter, so called because of its unusual arrangement of the central bracing that supported the upper wing. It too carried a single Vickers gun for the pilot atop the forward fuselage, and also a moveable Lewis gun mounted on a Scarff ring in the rear cockpit. The Strutter could generally handle itself when scrapping with German fighters, and was also used for both short and long reconnaissance missions. The big FE.2bs and 2ds were still very much in evidence and were not attacked without care and attention by the German pilots.

Fighters with the Royal Naval Air Service had for some months been helping to support their RFC comrades, several squadrons taking turns to move down from the North Sea coast area to support the hard-pressed British front. They too had begun to equip with Pups, and Strutters, but were also using French Nieuport Scouts, as the RFC had also been flying. Among the high-scoring British pilots still alive as 1917 began were the mercurial Albert Ball, with thirty-one victories, although he was back in England at this time. E. O. Grenfell had eight, J. O. Andrews seven and S. H. Long, six; J. D. Latta, had five although he was no longer in France. In the RNAS, R. S. Dallas had claimed six, including two flying the new Sopwith Triplane that this Australian was trialling in France. However, the best results went to his fellow Australian, S. J. Goble, who had scored eight by this time, flying Nieuports and Pups. In fact he scored the Pups first kill in the war, downing a German two-seater on 24 September 1916, which brought him the Distinguished Service Cross.

On the French Front, their fighter aircraft were the Nieuport Scout and Spad VII. Georges Guynemer and Charles Nungesser were the two leading lights, with twenty-five and twenty-one victories. In addition, Guynemer had been credited with four probables.

The French system of crediting aerial victories was, on the face of it, more stringent than the RFCs. Unless an enemy aircraft was seen to crash and be witnessed by two other sources it was only noted as probably destroyed and not included in the pilots score of victories. Similarly, an opponent who was only seen to spin away out of sight, or into cloud, was also only noted as a probable. An enemy in flames, or where the pilot jumped out, also had to be verified by witnesses. The British system of course added probable victories (recorded as out of control) to a pilots overall score. The French system could not have been always as stringent as it might seem, but it was the system. Early French aces still alive as 1917 began were:

| Ren Dorme | 17 (and 6 probables) |

| Alfred Heurtaux | 16 (and 3 probables) |

| Jean Navarre | 12 (before seriously wounded, 17 Jun 1916) |

Next page